Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Monna Vanna, 1866, oil on canvas, 88.9 x 86.4 cm (Tate, London)

Art for the sake of art

The Aesthetic Movement, also known as “art for art’s sake,” permeated British culture during the latter part of the 19th century, as well as spreading to other countries such as the United States. Based on the idea that beauty was the most important element in life, writers, artists, and designers sought to create works that were admired simply for their beauty rather than any narrative or moral function. This was, of course, a slap in the face to the tradition of art, which held that art needed to teach a lesson or provide a morally uplifting message. The movement blossomed into a cult devoted to the creation of beauty in all avenues of life from art and literature, to home decorating, to fashion, and embracing a new simplicity of style.

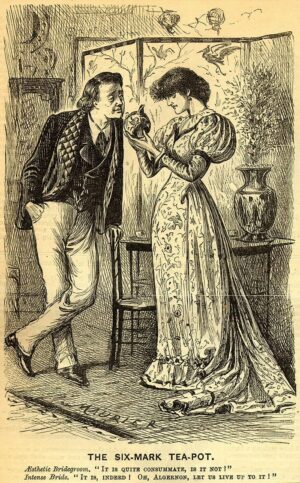

George Du Maurier, “The Six-Mark Tea-Pot” in Punch, October 30, 1880 (caption reads: Aesthetic Bridegroom. “It is quite consummate, is it not?” Intense Bride. “It is, indeed! Oh, Algernon, let us live up to it!”)

In literature

In literature, aestheticism was championed by Oscar Wilde and the poet Algernon Swinburne. Skepticism about their ideas can be seen in the vast amount of satirical material related to the two authors that appeared during the time. W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, masters of the comic operetta, unfavorably critiqued aesthetic sensibilities in Patience. The magazine Punch was filled with cartoons depicting languishing young men and swooning maidens wearing aesthetic clothing. One of the most famous of these, “The Six-Mark Tea-Pot” by George Du Maurier published in 1880, was supposedly based on a comment made by Wilde. In it, a young couple dressed in the height of aesthetic fashion and standing in an interior filled with items popularized by the Aesthetes—an Asian screen, peacock feathers, and blue and white porcelain—comically vow to “live up” to their latest acquisition.

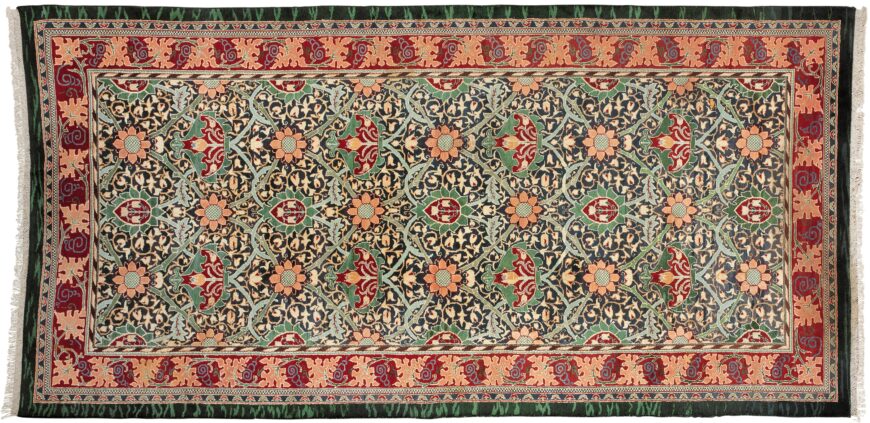

Morris & Company, Carpet, c. 1884, hand-knotted wool pile, 315 x 656 cm (Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide)

In the visual arts

In the visual arts, the concept of art for art’s sake was widely influential. Many of the later paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, such as Monna Vanna, are simply portraits of beautiful women that are pleasing to the eye, rather than related to some literary story as in earlier Pre-Raphaelite paintings.

A similar approach can be seen in much of the work of Sir Edward Burne-Jones, whose The Golden Stairs captures the aesthetic mood in its presentation of a long line of beautiful women walking down a staircase, devoid of any specific narrative content. The designer William Morris, another disciple of Rossetti, created beautiful designs for household textiles, wallpaper, and furniture to surround his clients with beauty.

James McNeill Whistler, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, 1862, oil on canvas 213 x 107.9 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

“flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”

Most famous of the aesthetic artists was the American James Abbott McNeill Whistler. His early painting Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl caused a sensation when it was exhibited after being rejected from both the Salon in Paris (the official annual exhibition) and the annual exhibition at the Royal Academy in London. The simplistic representation of a woman in a white dress, standing in front of a white curtain was too unique for Victorian audiences, who tried desperately to connect the painting to some literary source—a connection Whistler himself always denied. The artist went on to create a series of paintings, the titles of which generally have some musical connection, which were simply intended to create a sense of mood and beauty. The most infamous of these, Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, appeared in an exhibition at London’s Grovesnor Gallery, a venue for avant-garde art, in 1877 and provoked the famous accusation from the critic John Ruskin that the artist was “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”

The ensuing libel trial between Whistler and Ruskin in 1878 was really a referendum on the question of whether or not art required more substance than just beauty. Finding in favor of Whistler, the jury upheld the basic principles of the Aesthetic Movement, but ultimately caused the artist’s bankruptcy by awarding him only one farthing in damages. In The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, a collection of essays published in 1890, Whistler himself pointed out the biggest problem for the aesthetic artist was that “the vast majority of English folk cannot and will not consider a picture as a picture, apart from any story which it may be supposed to tell.”

No story or moral message

The Aesthetic Movement provided a challenge to the Victorian public when it declared that art was divorced from any moral or narrative content. In an era when art was supposed to tell a story, the idea that a simple expression of mood or something merely beautiful to look at could be considered a work of art was a radical idea. However, in its assertion that a work of art can be divorced from narrative, the ideas of the Aesthetic Movement are an important stepping-stone in the road towards modern art.

Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860–1900 from Victoria and Albert Museum on Vimeo.

Additional resources

Aestheticism at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

William Morris at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Aesthetic Movement” from The Guardian