The greatest minds of the High Renaissance worked on this vast church. Construction took more than a century.

Saint Peter’s Basilica (Basilica Sancti Petri), Vatican City, begun 1506, completed 1626. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Architects and designers included: Donato Bramante (whose design won Julius II’s competition); Antonio da Sangallo, a student of Bramante (the Pauline Chapel); Fra Giocondo (strengthening of the foundation); Raphael and Fra Giocondo (whose redesigned building plan was not executed); Michelangelo (design of the dome, crossing, and exterior excluding the nave and facade); Giacomo della Porta (design of the cupola); Carlo Maderno (extension of Michelangelo’s plan, adding a nave and grand facade); Gian Lorenzo Bernini (addition of the piazza, the Cathedra Petri, and the Baldacchino)

Numerous architects, Saint Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City, begun 1506, completed 1626 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

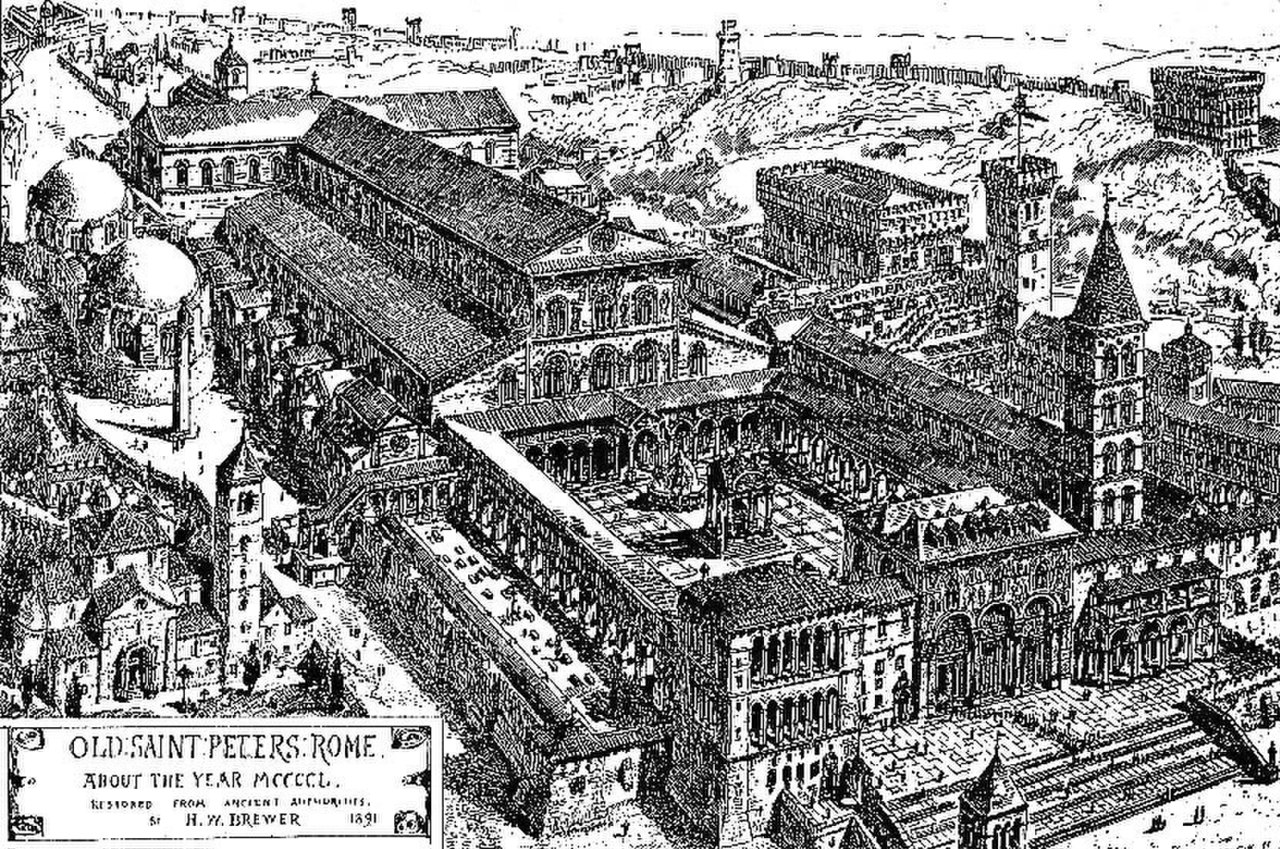

Pope Julius II commissioned Bramante to build a new basilica—this involved demolishing the Old St Peter’s Basilica that had been erected by Constantine in the 4th century. This ancient church was in disrepair. But tearing it down was a bold maneuver that gives us a sense of the enormous ambition of Pope Julius II, both for the papacy as well as for himself.

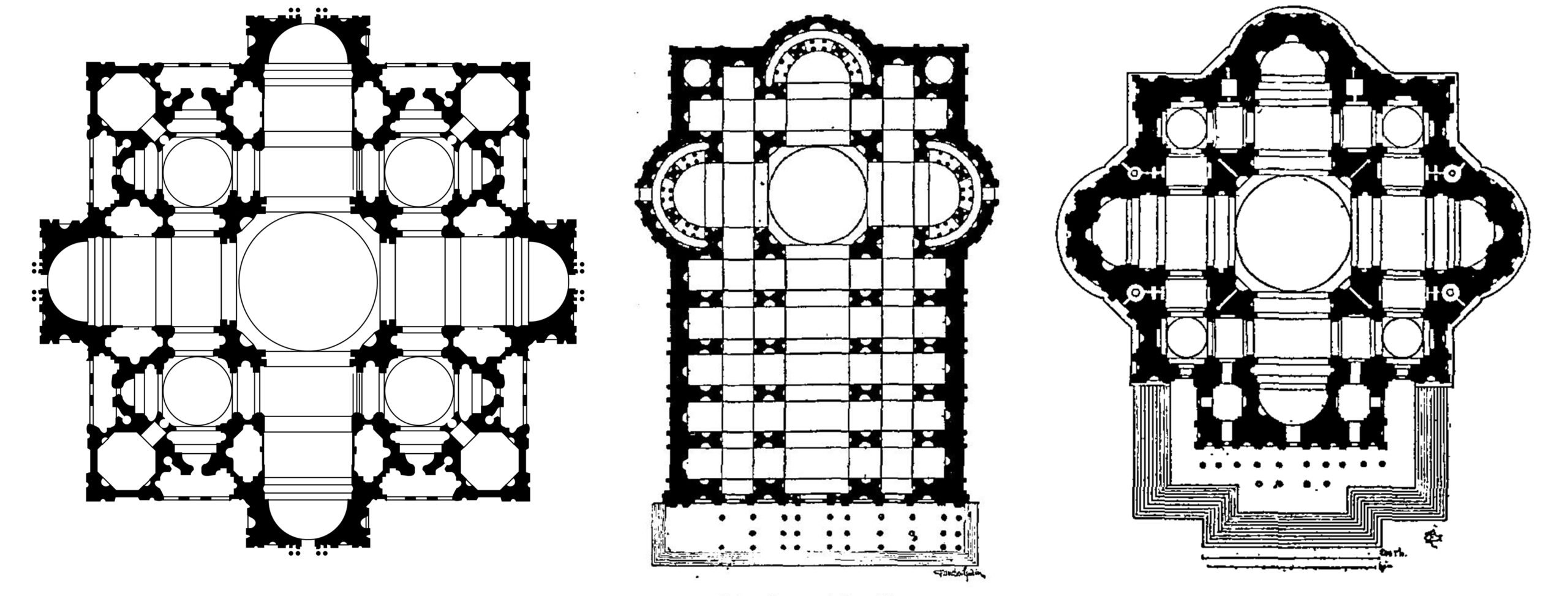

Left to right: Bramante, plan for Saint Peter’s Basilica, 1506; Raphael, plan for Saint Peter’s Basilica, 1513; Michelangelo, plan for Saint Peter’s Basilica, 1547

Burial site of Saint Peter

The site is a very holy one—it is (according to the Catholic Church) the site of the burial of Saint Peter. Bramante did the first plan for the new church. He proposed an enormous centrally planned church in the shape of a Greek cross enclosed within a square with an enormous dome over the center, and smaller domes and half-domes radiating out. When Bramante died, Raphael took over as chief architect for Saint Peter’s, and when Raphael died, Michelangelo took over. Both Michelangelo and Raphael made substantial changes to Bramante’s original plan. Nevertheless, the experience of being inside Saint Peter’s is awe-inspiring.

Nave, numerous architects, Saint Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City, begun 1506, completed 1626 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Basilica and central plan

The two basic types of churches are the basilica and the central plan. The basilica, with its long axis that focuses attention on the altar, has been the most popular type of church plan because of its practicality.

The other popular type of church plan is a central plan that is usually based either on the shape of a circle or on a Greek cross. These are called central plans because the measurements are all equidistant from a center. This type of church, influenced by Classical architecture (think of the Pantheon), was very popular among High Renaissance architects. Besides the influence of ancient Roman architecture, the circle had spiritual associations. The circle, which has no beginning and no end, symbolized the perfection and eternal nature of God. For some thinkers in antiquity and the Renaissance, the universe itself was constructed in the form of concentric circles with the sun, moon, and stars moving in circular orbits around the earth.

Bramante’s original design was for a central plan, however—as built—the church combines elements of a central plan with the longer nave of a basilica.