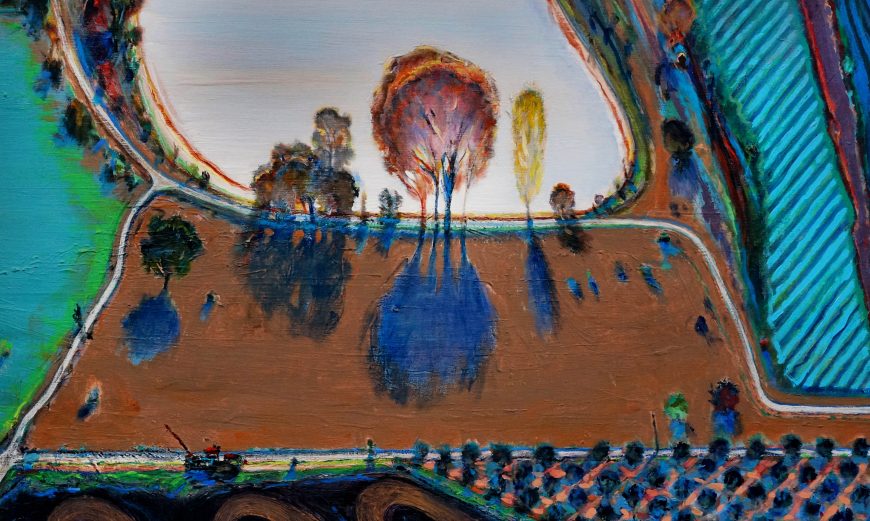

Through portraiture, Conteh expresses the love and care between a father and his children.

Alfred Conteh, Our Greatest Inheritance, 2024, acrylic and urethane plastic on canvas, 304.8 cm x 213.36 cm (Peoria Riverfront Museum) © Alfred Conteh. Speakers: Everley Davis, Assistant Curator and Community Engagement Coordinator, Peoria Riverfront Museum and Beth Harris, Smarthistory