Aphrodite of Knidos, torso: Roman copy, 2nd century C.E., restoration, 17th century, marble (Rome, Roman National Museum, Palazzo Altemps)

In 1972, the artist Eleanor Antin decided she would make an “academic” sculpture:

“I got out a book on Greek sculpture, which is the most academic of all….This piece was done in the method of the Greek sculptors…carving around and around the figure and whole layers would come off at a time until finally the aesthetic ideal had been reached.”

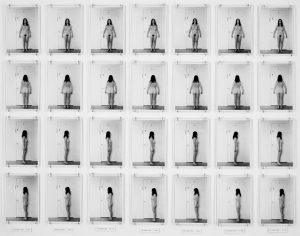

Of course she did no such thing—make an academic sculpture, that is. What she produced instead was a work entitled Carving: A Traditional Sculpture in which the typical marble or bronze medium of sculpture was replaced with a grid of 148 black and white photographs of the artist’s naked body. They are arranged in 37 vertical columns, corresponding to the number of days Antin spent following a diet plan proposed in a popular magazine for women. Each row consists of four photographs showing back, front, and side profiles, with a text panel at the bottom listing each day, time, and the artist’s weight. When first exhibited, the photographs were simply pinned to the wall, eschewing the conventional use of frames in the display of art.

Eleanor Antin, Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, 1972, 148 gelatin silver prints and text panels, each photograph 17.7 x 12.7 cm (The Art Institute of Chicago)

It is not sculpture per se, but the performance of sculpture. We might think of it as sculpture transposed into a living form, which is then presented as documentation—an analytical practice somewhat akin to laboratory research. The result might seem more informational than artistic.

Critiquing representations of women

Carving: A Traditional Sculpture could be seen as one answer to the rhetorical question posed by art historian Linda Nochlin’s now famous essay published one year earlier: “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Nochlin’s argument was that the history of art included few women, not because there were few women artists of note, but because art history was an extension of a patriarchal system in which women were excluded from almost everything. The answer Nochlin proposed was not to simply re-insert women into history, but to scrutinize the very structure of history itself: to analyze the role of women within patriarchy, and by extension in the history of art.

Eleanor Antin, Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, 1972 (detail) (Henry Moore Foundation)

Antin’s “traditional” sculpture is a witty and humorously feminist attack on tradition in which women were more often subjects than authors. Antin took the idea of sculpture as the subject of her work, thereby also following the dictates of Conceptual art, a dominant movement of the 1970s in which traditional notions of art were contested and redefined. Women artists at this time, in tandem with second wave feminism, embraced the Conceptual art movement’s focus on concepts and processes, its adaptation of new media, and its overturning of past artistic conventions.

Though the ancient Greeks predominantly sculpted male bodies, the lasting tradition of Western art, which was rooted in the classical ideal of ancient Greek and Roman art, was one in which the bodies of women served as primary subject matter. Subjected to scenarios of violence and abduction, and the distortion, abstraction and idealization that supposedly served the higher goals of art, that tradition became a key target of feminist interventions into visual culture in the 1970s.

Dispensing with clichéd notions of beauty and femininity, in this piece Antin presents her body for the purposes of critical analysis (signaled by the detached presentation in black and white) rather than visual pleasure, thereby presenting a critique of the ways women had been depicted in the history of art. However, it was not just the Western tradition of fine art that Antin interrogated in this conceptual sculpture. Popular culture similarly demands that women hold to an idealized form of femininity. Antin’s joining of these two mutually reinforcing systems—the weight loss program found in a typical “women’s” magazine and the chiseling away of stone to reveal an ideal form in academic art—became the template for women artists in the 1970s and 1980s who were interested in examining cultural representations of gender. (Mary Kelly and Cindy Sherman are two other important examples.)

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974-79, 1463 x 1463 cm (Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum)

Socially constructed, or essentially feminine?

Antin’s Carving: A Traditional Sculpture was one of the first artworks that looked critically at how women are portrayed within the contexts of both art and popular culture, but it represented only one strand of feminist art in the 1970s. Antin’s work could be viewed as an example of “social constructionism.” According to this way of thinking, imagery of women was seen as constructing, rather than simply reflecting, concepts of femininity.

A different school of thought, called “essentialism,” argued that a truly feminist art meant finding and highlighting an essential female aesthetic experience. Instead of analyzing women’s experience in relation to patriarchy, this approach argued that women’s art should be celebrated as separate in its own right. Judy Chicago’s massive installation The Dinner Party is an example of this theory. Created between 1974 and 1979, this work embodied a sense of essential femininity through a collaborative project that employed several hundred volunteers specialized in crafts (embroidery and ceramics, for example) that were typically associated with the domestic labor commonly practiced by women. The end result was a triangular dinner table with place settings dedicated to famous women in history and myth.

Helen Frankenthaler, Mountains and Sea, 1952, oil and charcoal on unsized, unprimed canvas, 219.4 × 297.8 cm (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

![]() Whatever the differences between these camps (and those differences would form a rich area of feminist scholarly debate in the years to come), by the 1970s the issue of gender could no longer be ignored. We can get a sense of how vastly different the new climate was when looking at a particular moment in a film, released the very next year, in 1973, after Antin first exhibited her work. Painters Painting: The New York Art Scene 1940-1970 was a documentary of the school of painting that had reigned since World War II. At one point in the film, the artist Helen Frankenthaler, known for her stained abstractions in which pools of color saturated the canvas, was asked “What was it like to be a woman painter?” Like many female modernists, Frankenthaler had faced the hostility of critics who claimed women did not have the wherewithal to produce the heroically large abstractions of their male counterparts. But Frankenthaler was clearly uncomfortable with the question. Despite the fact that she had just given an impressive overview of the history of modernist painting and the problems it represented for her own generation of artists, Frankenthaler’s only response to this question was a brief one—“well first of all I am a painter”—followed by an averting of her eyes. For the younger generation that came of age in the 1960s, this was no longer a tenable position. The personal was political, as the saying would go, but so too was the aesthetic.

Whatever the differences between these camps (and those differences would form a rich area of feminist scholarly debate in the years to come), by the 1970s the issue of gender could no longer be ignored. We can get a sense of how vastly different the new climate was when looking at a particular moment in a film, released the very next year, in 1973, after Antin first exhibited her work. Painters Painting: The New York Art Scene 1940-1970 was a documentary of the school of painting that had reigned since World War II. At one point in the film, the artist Helen Frankenthaler, known for her stained abstractions in which pools of color saturated the canvas, was asked “What was it like to be a woman painter?” Like many female modernists, Frankenthaler had faced the hostility of critics who claimed women did not have the wherewithal to produce the heroically large abstractions of their male counterparts. But Frankenthaler was clearly uncomfortable with the question. Despite the fact that she had just given an impressive overview of the history of modernist painting and the problems it represented for her own generation of artists, Frankenthaler’s only response to this question was a brief one—“well first of all I am a painter”—followed by an averting of her eyes. For the younger generation that came of age in the 1960s, this was no longer a tenable position. The personal was political, as the saying would go, but so too was the aesthetic.

Additional resources:

This work at the Art Institute of Chicago

The Dinner Party at the Brooklyn Museum

Eleanor Antin cited in Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock, eds, Framing Feminism: Art and the Women’s Movement 1970-1985 (Pandora Press, 1987), p.271.

Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” (1971) in Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays (Thames & Hudson,1989).

Painters Painting: The New York Art Scene 1940-1970, 1973, documentary directed by Emile de Antonio.