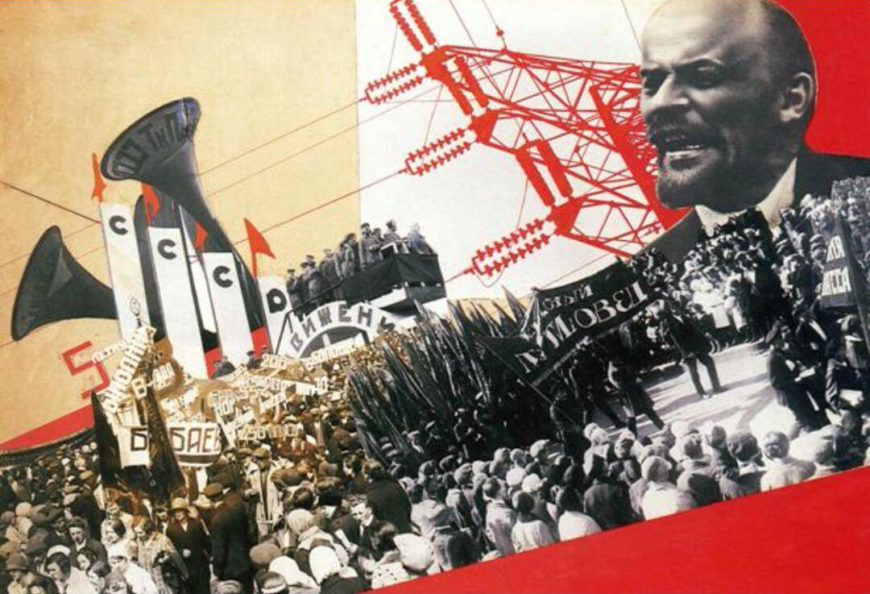

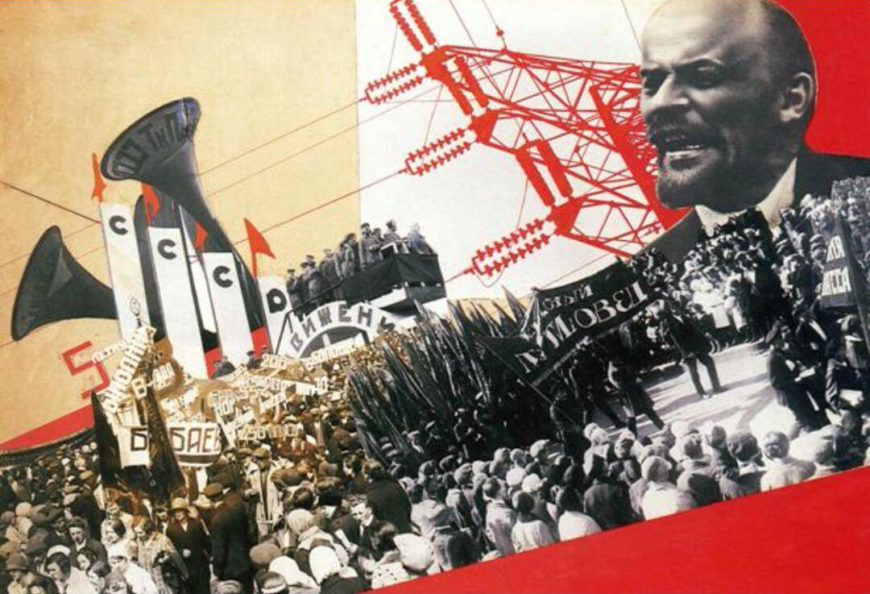

Varvara Stepanova, The Results of the First Five-Year Plan, 1932 (State Museum of Contemporary Russian History, Moscow)

Photomontage in the Soviet Union

Have you ever wondered what came before Photoshop? After the First World War, artists in Germany and the Soviet Union began to experiment with photomontage, the process of making a composite image by juxtaposing or mounting two or more photographs in order to give the illusion of a single image. A photomontage can include photographs, text, words, and even newspaper clippings.

Attributed to Mikhail Kaufman, Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova in their studio, 1922, photograph (© Rodchenko Stepanova Archive, Moscow)

Russia had for centuries been an absolute monarchy ruled by a tsar, but between 1905 and 1922 the country underwent tremendous change, the result of two wars (World War I, 1914–18 and Civil War, 1917–22) and a series of uprisings that culminated in the October Revolution of 1917. The Union of Socialist Soviet Republics (USSR) was established in 1922 under Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. The young communist state was celebrated by many artists and intellectuals who saw an opportunity to end the corruption and extreme poverty that defined Russia for so long.

The Russian avant-garde had experimented with new forms of art for decades and in the years after the Revolution, photomontage became a favorite technique of artists such as El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko, and Varvara Stepanova. Stepanova was a talented painter, designer, and photographer. She defined herself as a constructivist and focused her art on serving the ideals of the Soviet Union. She was a leading member of the Russian avant-garde and later in her career, she became well known for her contributions to the magazine USSR in Construction, a propagandist publication that focused on the industrialization of the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin, a ruthless dictator who took power after Lenin’s death and who’s totalitarian policies are thought to have caused suffering and death for millions of his people.

Propaganda

The public targeted by USSR in Construction was mostly foreign. The purpose of the magazine was to show countries such as France and Great Britain that the USSR was also a leading force in the global market and economy. By choosing to include images rather than just articles, the public would be able to see with their own eyes the accomplishments achieved under Stalin. At first the subjects depicted were strictly industrial, but as the magazine gained recognition and readers, topics diversified, and included subjects from education to sports and leisure. Soviet strategists were well aware that many European countries were witnessing the rise of a small base of devoted Communists, despite general mistrust and even contempt by the continental social and political elite.

As its title suggests, this photomontage is an ode to the success of the First Five-Year Plan, an initiative started by Stalin in 1928. The Plan was a list of strategic goals designed to grow the Soviet economy and accelerate its industrialization. These goals included collective farming, creating a military and artillery industry and increasing steel production. By the end of the First Five-Year Plan in 1933, the USSR had become a leading industrial power, though it’s worth noting that contemporary historians have found that economists from the USSR inflated results to enhance the image of the Soviet Union. In this work of art, Stepanova has also used the tools of the propagandist. This photomontage is an ideological image intended to help establish, through its visual evidence, the great success of the Plan.

Varvara Stepanova, The Results of the First Five-Year Plan, 1932 (State Museum of Contemporary Russian History, Moscow)

Constructing the image

In Stepanova’s photomontage, everything is carefully constructed. The artist uses only three types of color and tone. She alternates black and white with sepia photographs and integrates geometric planes of red to structure the composition. On the left, Stepanova has inserted public address speakers on a platform with the number 5, symbolizing the Five Year Plan along with placards displaying the letters CCCP, the Russian initials for USSR. The letters are placed above the horizon as is a portrait of Lenin, the founder of the Soviet Union. The cropped and oversized photograph of Lenin shows him speaking; his eyes turned to the left as if looking to the future. Lenin is linked to the speakers and letter placards at the left by the wires of an electrical transmission tower. Below, a large crowd of people indicate the mass popularity of Stalin’s political program and their desire to celebrate it.

Red, the color of the Soviet flag, was often used by Stepanova in her photomontages. She also commonly mis-matched the scale of photographic elements to create a sense of dynamism in her images. Despite the flat, paper format, different elements are visually activated and can even seem to ‘pop out.’ Several clear artistic oppositions are visible in The Results of the First Five-Year Plan. For example, there is a sharp contrast between the black and white photographs and the red elements, such as the electric tower, the number 5, and the triangle in the foreground. Our eyes are attracted to these oppositions and by the contrast between the indistinct masses and the individual portrait of Lenin, as an implicit reference to the Soviet political system.

Manipulating reality

As the term photomontage suggests, images are combined and manipulated to express the message the artist wants to convey. This image celebrating of the results of the First Five-Year Plan is the artist’s interpretation of events, under the strict supervision of Party ideologues.

The Plan resulted in radical measures that forced farmers to give up their land and their livestock. Many people were reduced to extreme poverty and famine became widespread. Terror, violence, and fear replaced the initial optimism about the Plan. What started as positive propaganda became, little by little, a means to hide a disastrous economic policy from the rest of the world. It became an absolute necessity for the State to project a pristine image of its society no matter how dire the situation became. Stepanova admits no fault or imperfection in The Results of the First Five-Year Plan.

Although Stepanova worked hand in hand with the Soviet government, her work shows great personal creativity. By using vibrant color, and striking images in a dynamic composition, she pioneered photomontage and revolutionized the way we now understand photography. Historical hindsight can make it difficult for contemporary viewers to engage the overtly propagandistic aspects of these images; in fact their exaggerated euphoria can even be mistaken for irony. Nevertheless, despite our increasingly sophisticated understanding of the distinction between image and reality, Stepanova’s photomontages are an important reminder of how an artist can blur the line between aesthetic passion and ideology.

Additional resources

Learn about the Russian Revolution

The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915-1932 (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1992).