Related works of art

In the Ancient Mediterranean

Masks

Active in c. 5000 B.C.E.–350 C.E. around the World

In North Africa

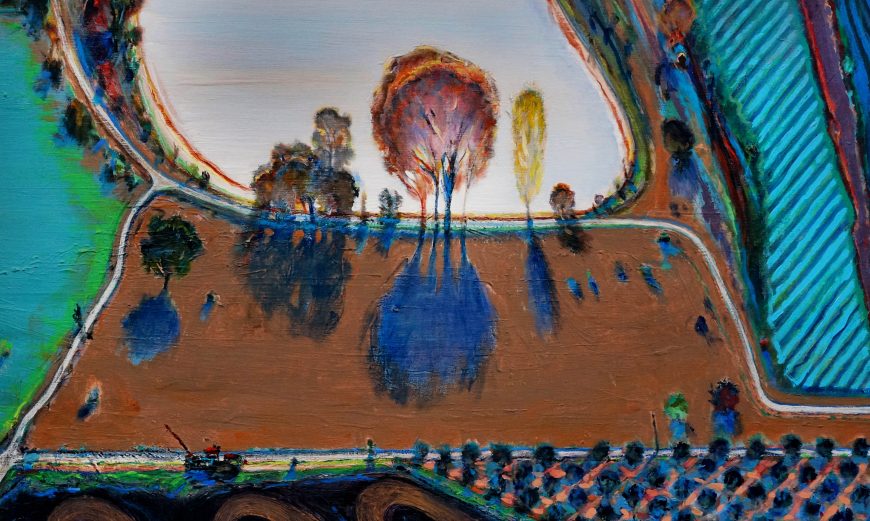

Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, Leaving My Reservation to Go to Ottawa and Fight for a New Constitution

1985

Canada

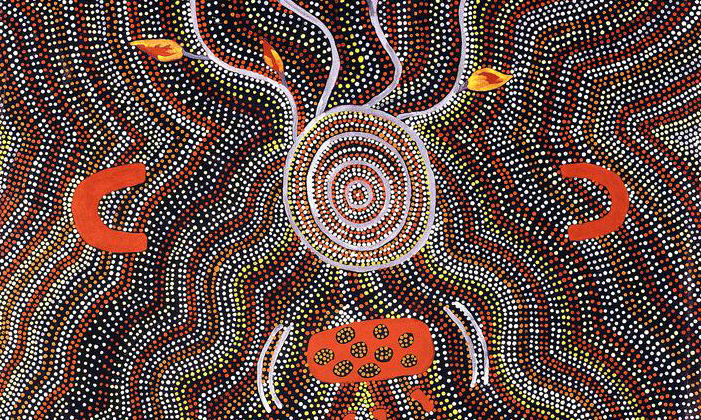

Lobsang Drubjam Tsering, Medicine Buddha Palace

2012–13 reproduction of a 17th-century original

Tibet

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!