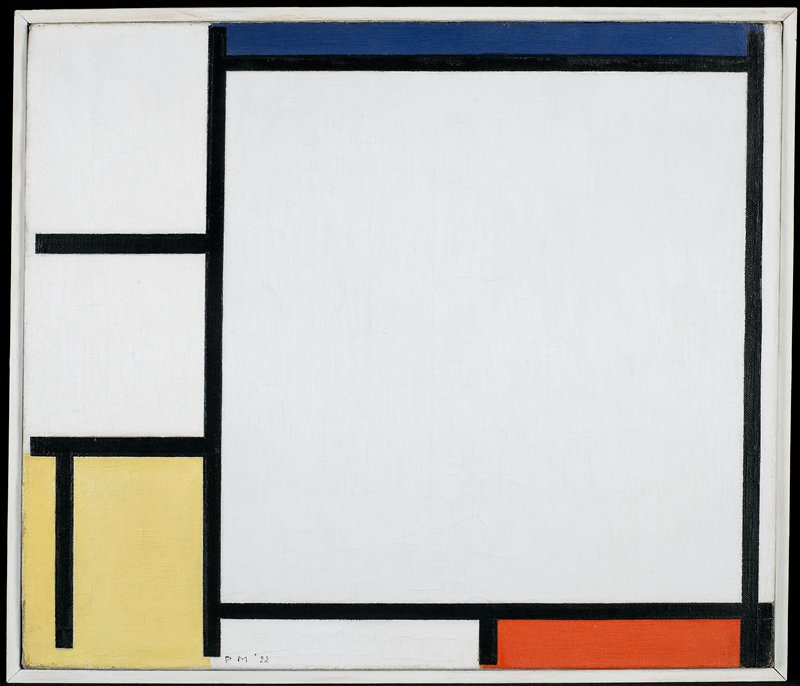

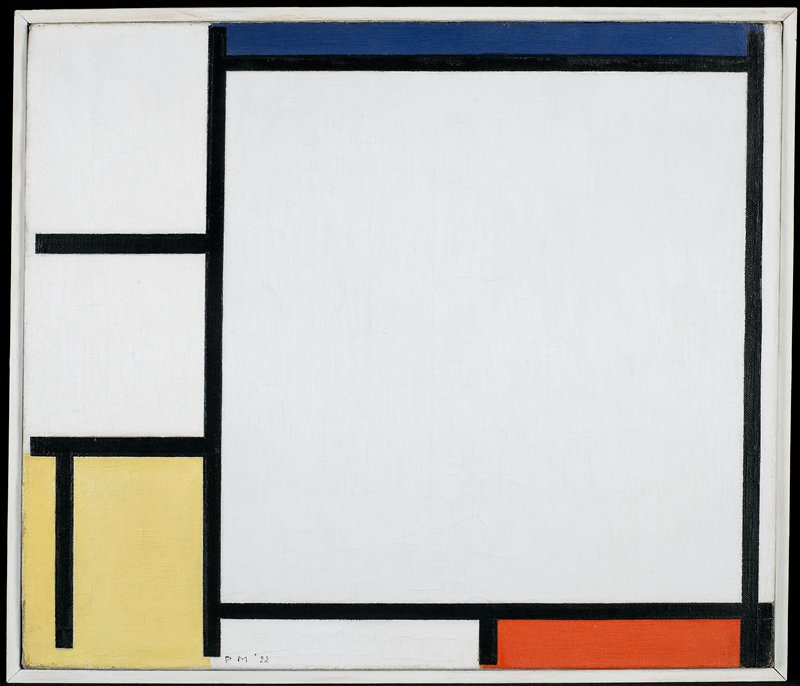

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Blue, Red, Yellow, and Black, 1922, oil on canvas, 41.9 x 48.9 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

De Stijl is one of the most recognizable styles in all of modern art. Consisting only of horizontal and vertical lines and the colors red, yellow, blue, black, and white, De Stijl was applied not only to easel painting but also to architecture and a broad range of designed objects from furniture to clothing. This is not inappropriate. Despite its close association with Piet Mondrian, the artist thought of it not as his personal style, but as De Stijl – The Style; it was objective and universal, applicable to all people and all things.

We will discuss De Stijl in three parts. This first part will introduce the elements of De Stijl, the second will examine the processes of abstraction that led to De Stijl, and the third part will examine the application of De Stijl to architecture and design.

De Stijl and Theosophy

Mondrian partially attributed his arrival at the elements of De Stijl to Theosophy, an occult philosophy promoted by thinkers such as Madame Blavatsky and Rudolf Steiner. Theosophists sought knowledge of higher, spiritual truths than those available to science, and often claimed to have access to those truths through direct spiritual insight. Mondrian became a member of the Dutch Theosophical Society in 1909, and painted a number of works around that time that explore mystical awareness.

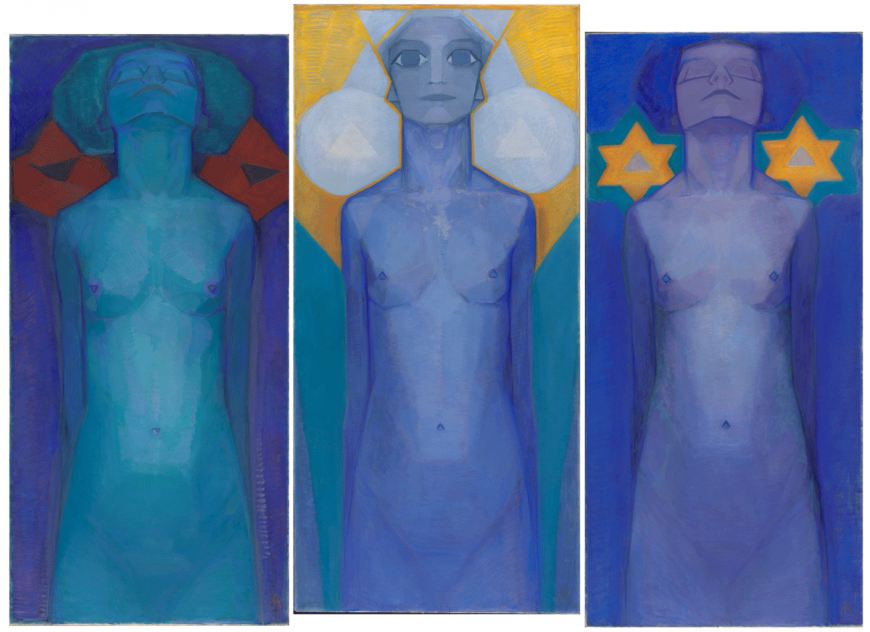

His Evolution triptych (1910-11) shows the “three spirits” that Madame Blavatsky described as living within humankind: terrestrial (on the left), sidereal or astral (on the right), and divine (in the center). Such works show Mondrian’s interest in finding a visual language for expressing spiritual things, but they are far from the radical abstraction that he later arrived at. In fact, allegorical paintings of spiritual and occult subjects have a long tradition, with roots in the nineteenth-century Symbolist movement, and even farther back in the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

While Theosophy certainly informed the spiritual goals of De Stijl, its influence on the actual style of De Stijl is less clear. The Dutch mathematician and Theosophist M. H. J. Schoenmaekers, whom Mondrian met in 1916, wrote an essay the year before in which he asserted that, “The three essential colors are yellow, blue, and red.” He also declared that, “The two fundamental and absolute oppositions that shape our planet are: the horizontal line of the earth’s trajectory around the Sun, and the vertical trajectory of the rays that emanate from the center of the sun.”[1]

These quotes are, however, just two examples from a torrent of wildly different suggestions that Theosophists made for visualizing the spiritual. Other artists influenced by Theosophy developed very different styles (Vassily Kandinsky and Hilma af Klint, for example). So why did the practitioners of De Stijl believe that their style was the most authentic expression of universal spirituality?

Blue, yellow, red, black, white

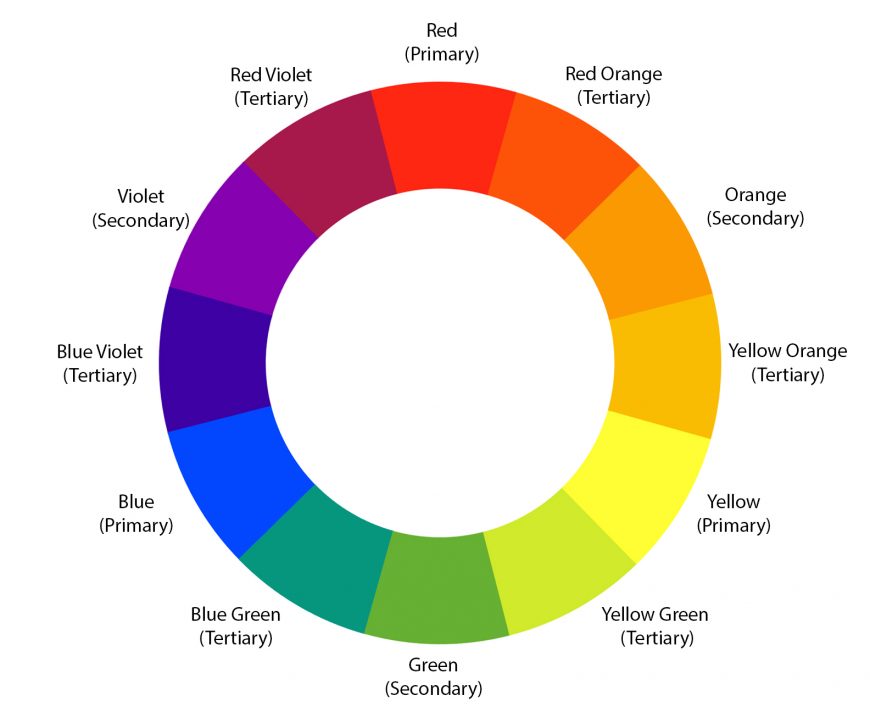

It helps to think of the elements of De Stijl as building-blocks: structural components that, in different combinations, can be used to make everything in the universe. Take for example De Stijl’s limited palette of red, yellow, and blue. These are what are called the “primary” colors, because if you had perfectly pure versions of each of these colors, you could create every other color. Red + yellow in different proportions create every shade of orange; blue + yellow create the shades of green; blue + orange create brown, and so on. Similarly, by combining black and white, you can make every shade of gray in between.

Red, yellow, and blue are “primary” colors in another sense as well. Although you can mix red and yellow to make orange, or red and blue to make violet, you cannot mix violet and orange, or even red-violet and red-orange, to make pure, primary red. It is for this reason that the artists of De Stijl could not have chosen orange, lavender, and teal. Not only are those colors impure (teal is a mixture of blue and green), they are also not fully representative of the color spectrum; if you had only those three colors you could never create red, yellow, or blue.

Color printers rely on this principle, although the primaries that work best in this case are cyan (a light greenish blue), magenta (a blueish red), and yellow. Together with black ink and the white of the page itself, a four-cartridge CMYK printer can reproduce every color in a photograph of you and your friend at the beach, from the subtle teals of the water, to the dull reddish-brown of the rocks, to the brilliant yellow of the sand.

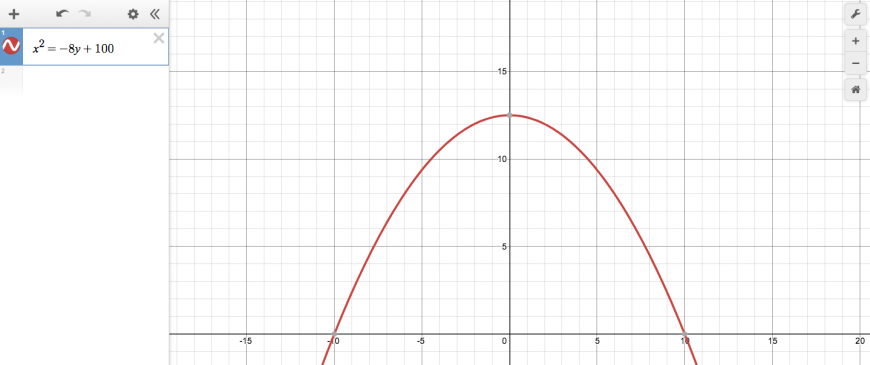

Coordinate grid of x2 = -8y + 100 (image: Desmos)

Horizontal and vertical lines

The justification for De Stijl’s use of only horizontal and vertical lines is somewhat trickier, and it helps to think of them not as ‘lines’ but as directional forces or vectors: dynamic structuring factors, rather than stable structural components. If you recall from working with coordinate planes in mathematics, any kind of regular line can be expressed in a formula that describes the movement of a point along a regular grid defined by ‘x,’ the horizontal axis, and ‘y’, the vertical axis.

A diagonal line at a forty-five degree angle would be expressed as x = y, for example: for every unit moved in a horizontal (x) direction, move the same unit in a vertical (y) direction. The parabola of a soccer ball punted upfield might be x2 = -8y +100. Thus any rational line could be expressed mathematically as a motion defined by two interacting forces, a horizontal force and a vertical force.

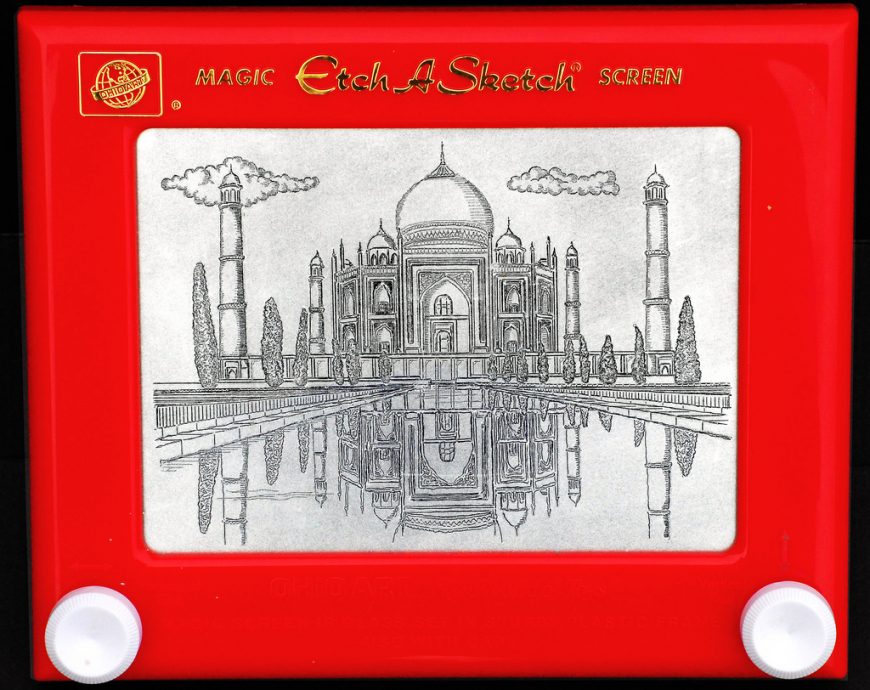

Taj Mahal drawn on an Etch-A-Sketch (photo: Etcha, CC BY-SA 3.0)

To put this into what may be more familiar terms, think of an Etch-a-Sketch machine. There are just two control knobs, one for the horizontal motion of a black line on the gray screen, and the other for vertical motion. But by simultaneously manipulating both knobs, you can draw diagonal or curved lines to create triangles and circles — or a baseball cap, a human face, and even a chaotic scribble that would seem impossible to reduce to an “x, y” formula.

De Stijl’s horizontal and vertical lines are like the shape-making vectors controlled by the Etch-a-Sketch knobs. In the same way that a printer combines just a few primaries to make any color, by manipulating the horizontal and vertical forces of an Etch-a-Sketch, you can draw anything in the universe, from a box, to a tree, to the Taj Mahal.

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Blue, Red, Yellow, and Black, 1922, oil on canvas, 41.9 x 48.9 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Building-blocks of the universe

To give one more analogy by way of conclusion, the elements of De Stijl are the artist’s equivalent of the physicist’s fundamental building blocks: protons, neutrons, and electrons. With a bucket of each of these atomic building blocks, you could make anything in the universe, from hydrogen (one proton + one electron), to oxygen (eight protons + eight electrons + eight neutrons), to water (two hydrogen atoms + one oxygen atom), to a protein, a paramecium, and eventually even a person.

Similarly, if you have buckets of pure red, yellow, blue, black and white paint, and a lot of skill on an Etch-a-Sketch machine, you could represent absolutely anything. It is in this sense that De Stijl is universal, “the” style, and not just the personal style of Piet Mondrian or the style of some specific region or period in time. Although our own historical moment tends to celebrate cultural and individual differences and reject “absolutes” or “universals,” De Stijl has a decent claim to being, as its name asserts, The Style for all things, all time, and all people everywhere.

Notes:

- M. H. J. Schoenmaekers, Het Nieuwe Wereldbeeld (Van Dishoeck: Bussum, 1915), pp. 224,

102 (authors’ translation).

Additional Resources:

Yve-Alain Bois, et.al., Piet Mondrian, 1872-1944 (Exhibition catalog: National Gallery of Art and MoMA, 1994).

Piet Mondrian, Harry Holtzman, and Martin S. James, The New Art–the New Life: The Collected Writings of Piet Mondrian (Boston: G.K. Hall, 1986).

Michel Seuphor. Piet Mondrian: Life and Work (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1969).