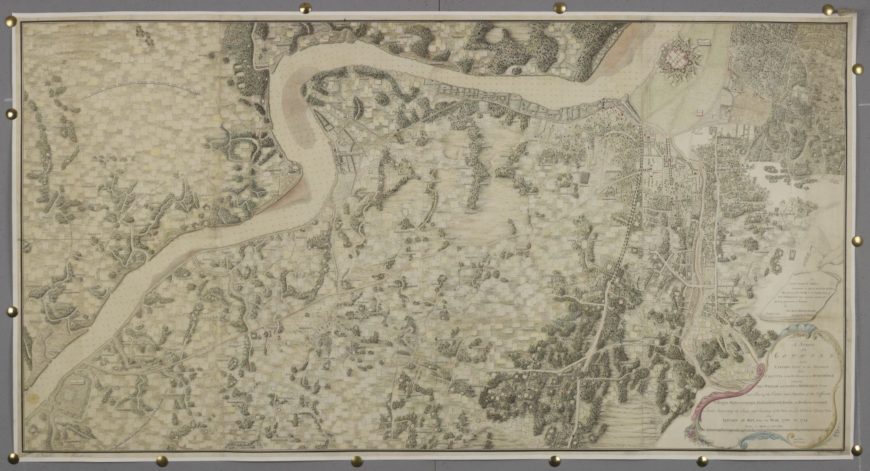

Survey of the country on the eastern bank of the Hughly, from Calcutta to the fortifications at Budgebudge. This is one of three surveys by Mark Wood, a Captain in the East India Company’s Bengal Army. A minutely-detailed survey drawn at a scale of 4 inches to a mile, the map shows the city of Kolkata (then known as Calcutta) in West Bengal and the land surrounding the River Hooghly.

Mark Wood’s display map, Survey of the country on the eastern bank of the Hughly, from Calcutta to the Fortifications at Budgebudge, is the largest of three similarly large-scale cartographic works by Wood in the British Library’s King George III’s Topographical collection. All are similar in appearance and function, and were produced around 1785 in Kolkata. The three maps represent overlapping landscapes along the banks of the River Hughly (Hooghly) and around the city of Kolkata. Two, including this one, were dedicated to Lieutenant General Robert Sloper (the recently appointed Commander-in-Chief of military operations in India) and the third to George III. These works were the final products of a survey of the Hooghly river that Wood oversaw between 1780 and 1785.

The producer

Mark Wood arrived in India with his brother George in 1770 as a cadet in the East India Company’s Bengal Army. Based on his dates, it is highly likely that he would have been taught draughtsmanship by the landscape artist Paul Sandby during his training at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich. [1] Wood exemplifies the social, financial and political ascendancy that a successful career in India could secure. When this map was produced, he had attained the rank of Captain. After completion of the survey, he was promoted to Surveyor General (Bengal), and two years later to Chief Engineer in Bengal. Having amassed an estimated £200,000 during his time in India, he purchased a country estate on his return to Britain in 1793 (Piercefield House, Monmouthshire, later moving to Gatton Park, Surrey), bought shares in the East India Company, was presented at Court, and entered Parliament. [2]

Surveying and the East India Company’s administration of India

In the aftermath of significant territorial acquisitions by the East India Company in the second half of the 18th century, surveying became crucial to the Company’s processes of colonial formation, knowledge and control. Surveys were not always conducted in a systematic or ongoing way, but in accordance with East India Company priorities at any given moment. Surveyors could be recalled to military duties when necessary (the campaigns of the Anglo-Mysore and Anglo-Maratha wars took place during the time frame of Wood’s survey, for example, affecting surveyors in the Company’s Madras and Bombay Presidencies). Additionally, surveys were produced not in order to acquire comprehensive geographical knowledge, but in order to facilitate specific colonial administrative priorities or programmes, for example, agricultural or policing. At the time that Wood was working on his survey, the police force in Kolkata had recently been augmented and strengthened considerably, and in 1784 he was also asked to work on the production of a map to facilitate policing of the city and its surroundings. The survey under discussion here, however, was originally undertaken – as the cartouche makes clear – ‘for military information’. The various military campaigns in India in this period necessitated the movement of large numbers of troops across considerable distances of difficult terrain on foot. It was therefore important that the kind of information provided by this map (‘villages, watercourses, embankments, tanks and broken ground’) was available to the East India Company’s armies. The map fixes not only space, but also time – it records the banks and depths of the Hooghly in the January – May period (i.e. prior to the monsoon season), and also annotates parts of the landscape which would be flooded later in the year. Earlier surveys of Bengal, such as James Rennell’s which covered a much larger area, did not attempt to articulate the landscape in this way. The attention that is paid in Wood’s map to the demarcation of property and land within the area surveyed additionally anticipates early 19th-century cadastral surveys, produced for the purposes of land taxation – by now one of the East India Company’s chief revenue streams. As Peter Barber and Tom Harper have pointed out, the original and cited military use of the map did not preclude other possibilities – the potential for additional administration of the land could be envisaged within the space of the map. [3]

Kolkata in the late 18th Century

Between 1706 and 1756, the British settlement at Kolkata had remained confined within a fortification. Fort William – as it was known – was destroyed in that year by the Nawab of Bengal’s forces. In the aftermath of the British success at the Battle of Plassey the following year, a new fort was constructed and a new settlement sprung up – this time, extending beyond the boundaries of the fort itself.

A view of Calcutta taken from Fort William. The original Fort William was destroyed in 1756, but a new one was built between 1758–1781 by Robert Clive on the east bank of the River Hooghly. Explore this item further.

The new fort – which was not completed until 1781 – can be seen towards the top right of the map, and the expanding city to its northeast. In the two other maps, the city is more fully represented and – in common with other maps of Kolkata produced in the late 18th and early 19th centuries – Wood restricts himself to delineating the ‘white town’, the British colonial settlement. This particular map ascribes ownership to residential buildings (particularly along Garden Reach – the suburb along the south bank of the Hooghly river, southwest of the fort) and includes recent and projected public constructions, including the prison, hospital, docks and the bridge at Alipore. The map is unique in articulating the precise ownership of the Garden Houses along the Hooghly and it is therefore useful for understanding how neighbourhoods and networks of East India Company employees in Kolkata may have operated.

It is notable – though not surprising – that in the two maps featuring Kolkata itself, Wood ignores the ‘black town’ which also fell within the compass of the represented landscape, despite the fact that substantial residences had been erected in it by wealthy native merchants. In this map he labels the native villages but does not delineate their features beyond recording the presence of constructions such as water tanks, which would have been of use to the Company’s army. The geographical information he accumulated was produced for the purposes of the colonial administrators, and was not an attempt to objectively render every physical and topographical feature of the landscape, despite its obvious attention to detail in some regards. As Matthew Edney has pointed out, surveyors and colonial administrators (despite their frequent claims for the rigour and comprehensiveness of their scientific approaches) could never hope to know the ‘real’ India – instead ‘what they did map, what they did create, was a British India’. [4]

Rural Kolkata

The emphasis of Wood’s map is not on the urban settlement of Kolkata but on its rural surroundings. It includes the suburb at Garden Reach, which featured a number of suburban dwellings along the river constructed in a Palladian (and Arcadian) mode reminiscent of the Thames-side villas built between Richmond and Hampton earlier in the 18th century.

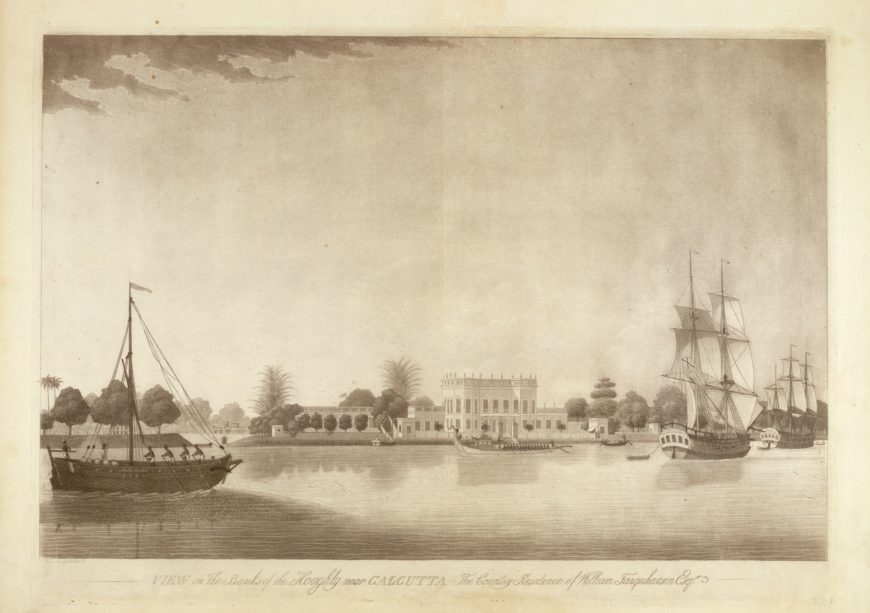

View on the banks of the Hooghly near Calcutta. This view of a house in the suburb of Garden Reach, Kolkata is similar to the views of houses on the banks of the River Thames in Richmond and Hampton that were popular in the 18th century. Explore this item further

Wood’s map details the footprints of the individual houses along Garden Reach, as well as the layout (trees, carriage drives, etc) of the extensive grounds that enveloped them. Known as garden houses, (translated from the Bengali bagan-bari) they were desirable country homes for the ‘opulent residents’ of Kolkata, providing respite from the city and its urban and administrative trials, and also allowing for a lifestyle that emulated the landed privilege of Britain’s social and cultural elite. [5] Mapping this location thus not only fulfilled the informational requirements of the survey project, but additionally served to visualise the spatial and social formation of Kolkata and its environs. The map articulates the geographical and social distances between the city and the country, and provides evidence of an emerging social stratification within British India that mirrored the established one back home in Britain. It is tempting to speculate that in purchasing the Piercefield Park estate on his return to Britain, Wood recognised the topographical correspondences between his new home and the suburban mapping that had contributed to his financial success. Situated close to the banks of the River Wye, and with distant views of the town of Chepstow, the neoclassical Piercefield House must have activated memories of Kolkata’s suburban topography and of the social distinction it conferred.

Purpose

Wood’s maps represent one kind of end product of an extensive and time-consuming survey. They were not produced for use, but as gifts, and they therefore evince considerable aesthetic appeal and skill. The two dedicatees of the three maps were figures with the power to progress Wood’s career in India and back at home, and the strategy of seeking favour from them appears to have been successful. The map gifted to George III may be compared with another gift that Wood gave to the King 10 years later when he was presented at court – an expensive ivory model of the new Fort William (a location which also appears in the map dedicated to King George).

Written by Rosia Dias

Rosie Dias is Associate Professor in the History of Art at the University of Warwick. She specialises in 18th and 19th century British art.

Originally published by The British Library (CC BY-NC 4.0)