Landscape painting is traditionally at the top of the hierarchy of Chinese painting styles. It is very popular and is associated with refined scholarly taste. The Chinese term for “landscape” is made up of two characters meaning “mountains and water.” It is linked with the philosophy of Daoism, which emphasizes harmony with the natural world.

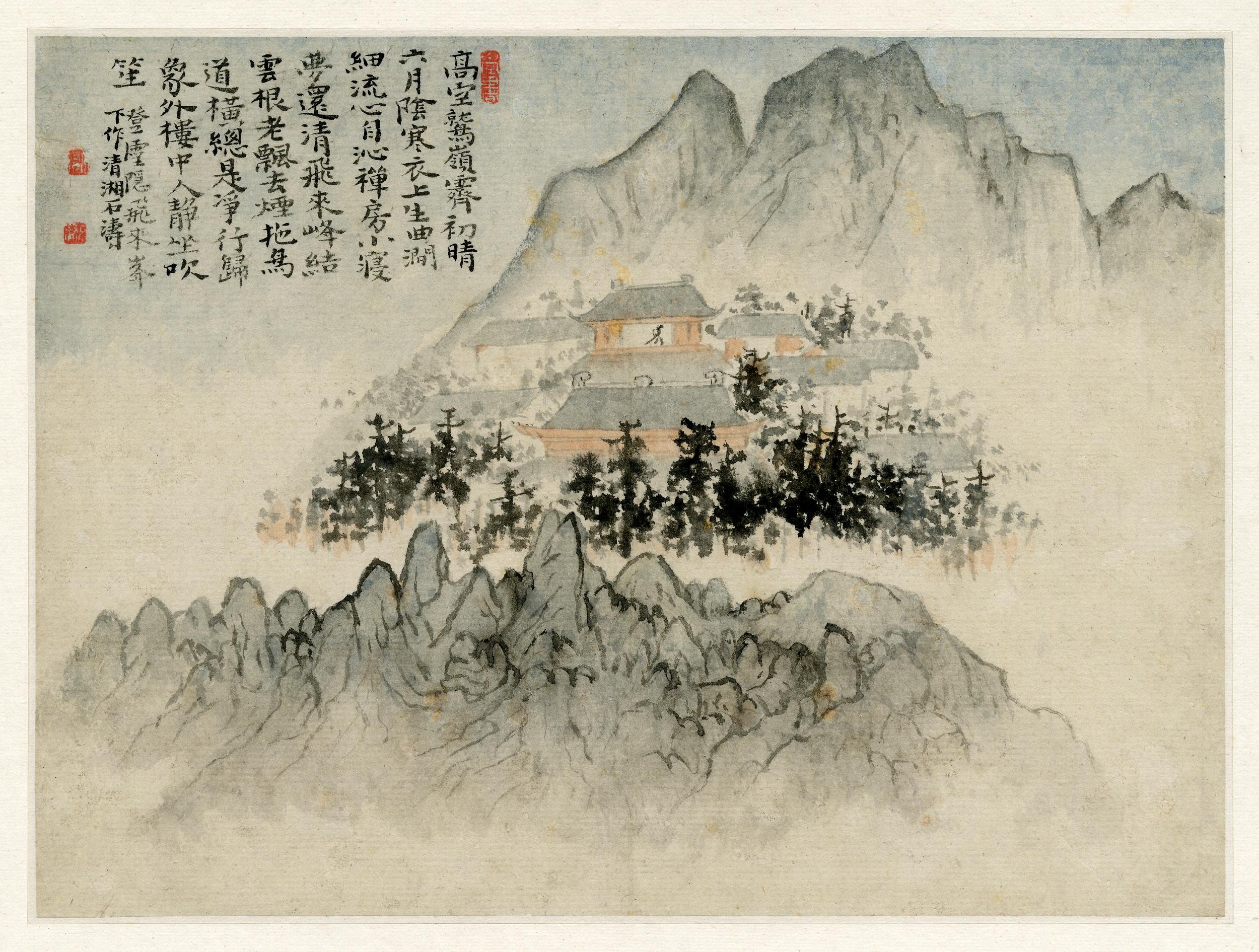

Shitao, Landscape, c.1698–1700, album leaf, ink and colour on paper, 20.8 cm high, China (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Idealized landscapes

Chinese artists do not usually paint real places but imaginary, idealized landscapes. The Chinese phrase woyou expresses this idea of “wandering while lying down.” In China, mountains are associated with religion because they reach up towards the heavens. People therefore believe that looking at paintings of mountains is good for the soul.

Chinese painting in general is seen as an extension of calligraphy and uses the same brushstrokes. The colors are restrained and subtle and the paintings are usually created in ink on paper, with a small amount of watercolor. They are not framed or glazed but mounted on silk in different formats such as hanging scrolls, handscrolls, album leaves and fan paintings.

Wenfangsibao, or the Four Treasures of the Scholar’s Studio: paper, brush, ink, and inkstone (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The scholar’s desk

In China, painters and calligraphers were traditionally scholars. The four basic pieces of equipment they used are called the Four Treasures of the Scholar’s Studio or wenfangsibao: paper, brush, ink and inkstone. A cake of ink is ground against the surface of the inkstone and water is gradually dropped from a water dropper, gathering in a well at one end of the stone. The brush is then dipped into the well and the depth of intensity of the ink depends on the wetness or dryness of the brush and the amount of water in the ink.

Ink cakes were made from carbonized pinewood, oil and glue, moulded into cakes or sticks and dried. The most prized inkstones were made of Duan stone from Guangdong province, although the one shown here is made of ceramic. Brushes had very pliable hairs, usually made from deer, goat, wolf or hare. Wrist rests gave essential support while painting details. Other equipment used on a scholar’s desk includes brush washers, seals, seal paste boxes, brush pots and brush stands.

Brush rest, 1573–1620 (Ming dynasty), porcelain, 10.9 x 16 cm, Jingdezhen, China (© Trustees of the British Museum)

In the seventeenth century print-painting manuals began to be designed to help train artists. These showed, step by step, how to paint in the style of particular artists. They illustrated a variety of subjects, from small rocks to mountains or tree branches to forests. The different brush strokes were named and explained.

The earliest landscapes

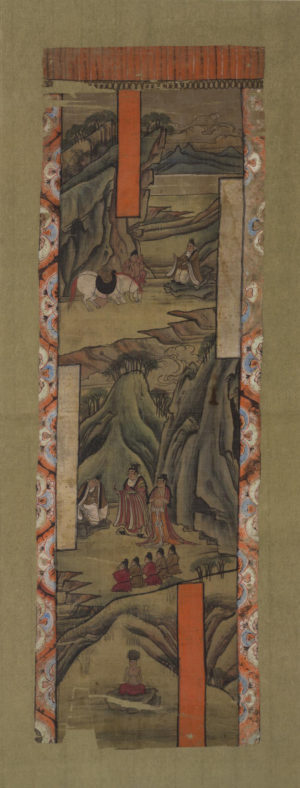

Scenes from the Life of the Buddha, ink and colors on silk, 8th–early 9th century (Tang dynasty), 69 x 19.3 cm, Cave 17, Mogao, near Dunhuang, China (© Trustees of the British Museum)

In China, the earliest landscapes were portrayed in three-dimensional form. Examples include mountain-shaped incense burners made of bronze or ceramic, produced as early as the Han Dynasty. The earliest paintings date from the sixth century. Before the tenth century, the main subject was usually the human figure.

In the period following the Han dynasty, Buddhism spread across China. Artists began to illustrate stories of the life of the Buddha on earth and to create paradise paintings. In the background of some of these brightly colored Buddhist paintings, it is possible to see examples of early landscape painting.

This scene is one of a series of three representing the life of the historical Buddha, Prince Sakyamuni, when he lived on earth. The mountains are simple triangles, and their ridges are painted with short brush strokes to create texture. The water in the river is portrayed in a bold, diagrammatic way, conveying a sense of movement.

Chinese paintings are usually created in ink on paper and then mounted on silk. This is done using different formats including hanging scrolls, handscrolls, album leaves, and fan paintings.

Admonitions scroll

The Admonitions handscroll is an important work in the history of Chinese art. The painting is one of the earliest on silk in China and is probably a sixth-century copy of an original painting by Gu Kaizhi. It illustrates episodes from an eighty-line poem entitled ‘The Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies’, written as a code of ethics for the women of the imperial court.

Admonitions Scroll (detail), [after] Gu Kaizhi (about 345–406), 6th–8th century C.E. (Tang dynasty), 24.37 x 343.75 cm, China (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Lantern-shaped porcelain vase, Kangxi Period (1662–1722), 22.8 cm high, Jingdezhen, China (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Landscapes painted on ceramics

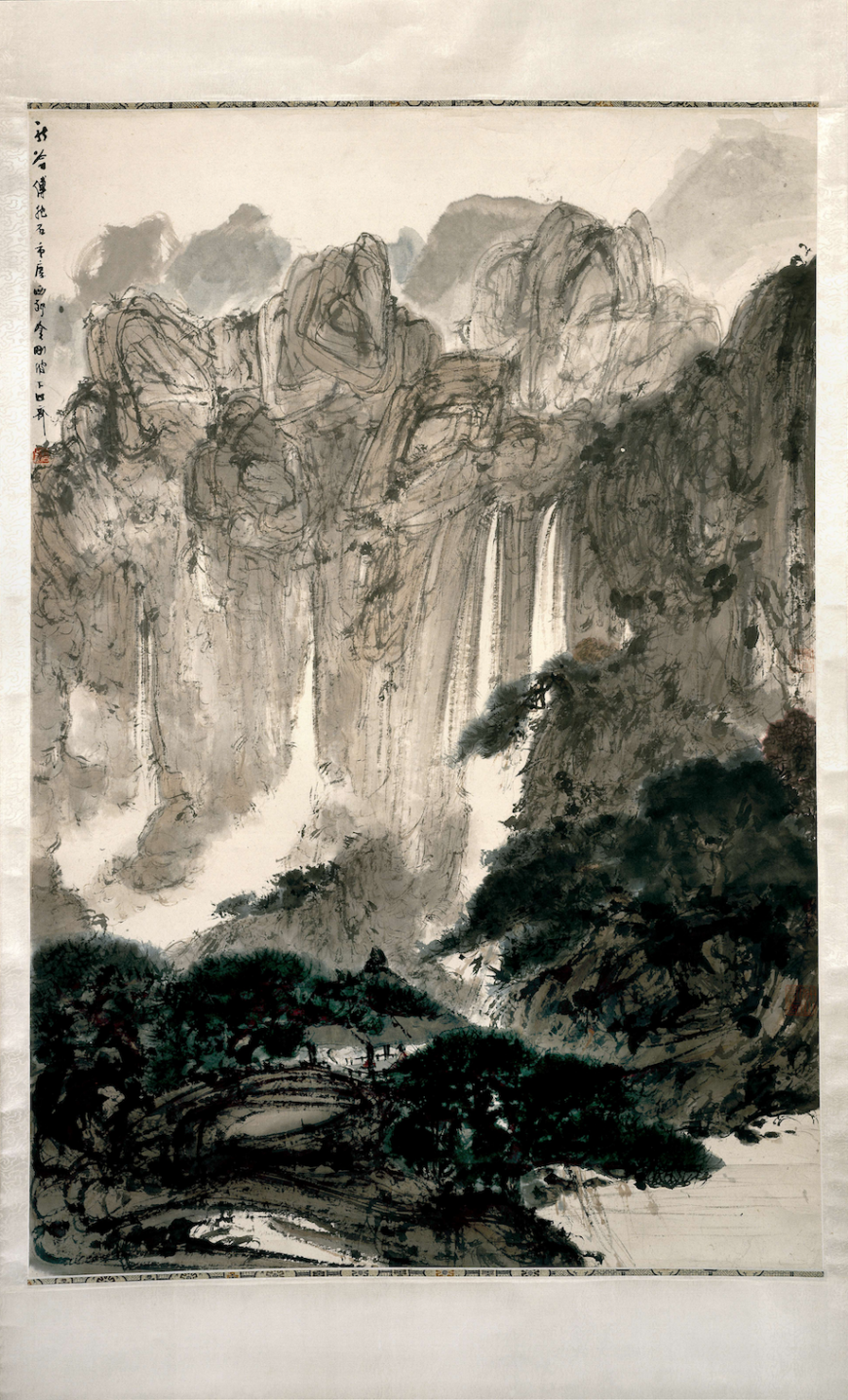

Fu Baoshi, Diamond Cliffs, 1939–46?, Jingangpo, painting, hanging scroll, 117 x 79 cm, Chongqing, China (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Until the seventeenth century, landscape painting was an art form associated with the elite. From this time, however, landscapes were transferred to ceramics, a medium that could be enjoyed and used by ordinary people. The status of the painted ceramics—with their bright cobalt blue underglaze and colored enamel—was much lower than that of more subtle ink painting.

Painted ceramics were produced for export, giving Europeans their first taste of Chinese painting. The painting on these export ceramics, however, was very different from the sort of painting that was highly valued in China.

This lantern-shaped porcelain vase, made during the Kangxi Period, is decorated with landscape scenes.

20th century

In modern times, landscapes remain an important part of Chinese painting. In this hanging scroll the tops of the mountains are painted in ink wash with rather wild spirals of brushwork winding in towards the centre. This shows Fu Baoshi’s interest in an earlier seventeenth-century individualist painter called Shitao, who also painted rocks like this. Fu Baoshi liked Shitao so much that he changed his name to Baoshi, which means ‘Treasuring Shi’.

Fu Baoshi studied in Japan in the 1930s. He worked at the ceramic centre of Jingdezhen and also taught painting in Nanjing and Chongqing, where he painted this in the early 1940s.

© Trustees of the British Museum