Essay by Moon Dongsoo

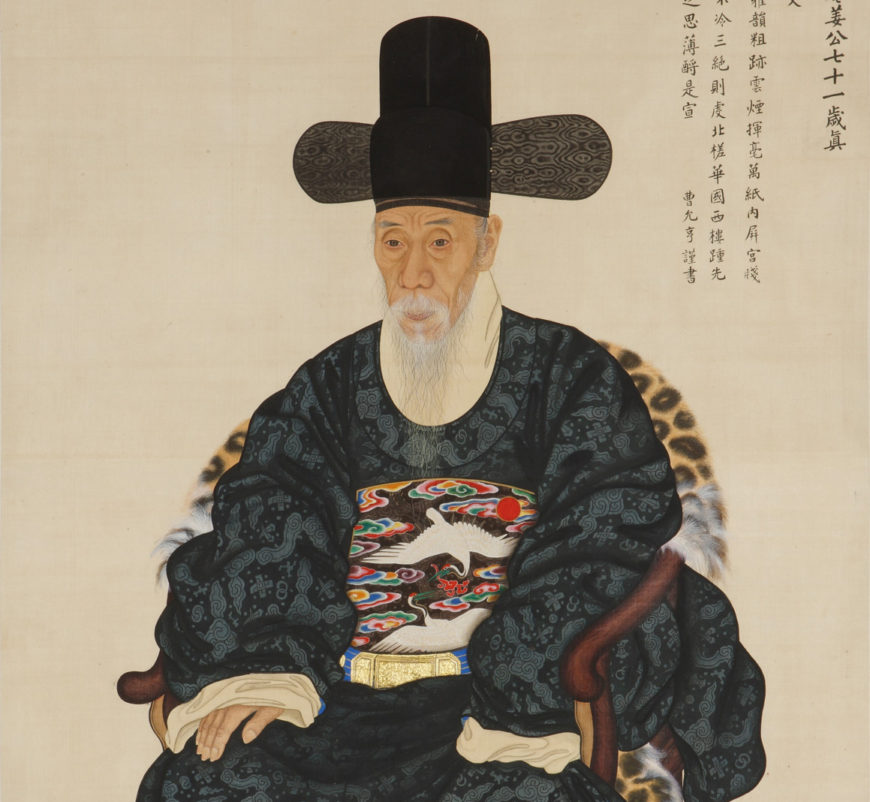

Yi Myeonggi, Portrait of Kang Sehwang, 1783 (Joseon Dynasty), ink and colors on silk, 145.5 x 94 cm, Treasure 590-2 (National Museum of Korea)

Our primary means of communicating with other people is our face. But over time, the skin, muscles, wrinkles, bones, and features of our face change, which in turn changes the appearance of our gaze, complexion, and facial expressions. Imbued with such traces of the past, our present face can thus serve as a map of our internal psychology.

Portraits of the Joseon Dynasty are known for their incredible attention to detail, depicting every tiny crease, curve, spot, or scratch on the subject’s face. But beyond merely attempting to duplicate these external features, Joseon artists strived to capture the subject’s internal temperament and personality in accordance with the principle of “jeonsin” (傳神), which was the belief that a person’s spirit can be transmitted through a portrait.

One of the finest examples of Joseon portraiture is Portrait of Kang Sehwang, which depicts the elderly Kang Sehwang. The many twists and turns of Kang’s long life can be traced through the deep vertical creases between his eyes. After losing his government post in his youth, Kang spent long hours in his study, contemplating various books and paintings. Only in his twilight years was he able to finally launch a successful political career. As such, this portrait is an important visual record offering a glimpse into the life and mind of an eighteenth-century literati scholar.

Detail, Yi Myeonggi, Portrait of Kang Sehwang, 1783 (Joseon Dynasty), ink and colors on silk, 145.5 x 94 cm, Treasure 590-2 (National Museum of Korea)

Life of Kang Sehwang

In this portrait, Kang is seated on a chair with hands resting on his thighs, the model of solemnity and refinement. The youngest of nine children, born into the wealthy and powerful Jinju Kang clan in Namsomun-dong, Seoul (present-day Jangchung), Kang was showered with affection by his family. Both his grandfather Kang Baeknyeon and father Kang Hyeon were honored members of giroso (耆老所), the Hall of Elderly Officials for high-ranking officials over the age of seventy. By the age of thirteen, Kang was an accomplished poet and calligrapher, and by fifteen, he was married to a woman from the Jinju Yu clan.

Kang’s family was associated with the conservative Namin faction of government officials, which had enjoyed prestige and power for generations. In the early eighteenth century, however, the progressive Noron faction gained power over Namin, and Kang’s family began to decline. Around this time, it was revealed that Kang’s eldest brother, Kang Seyun, had illegally passed the civil service examinations in 1713 (coincidentally the year of Kang Sehwang’s birth) through his father’s influence. Then in 1728, it was disclosed that Kang Seyun had taken part in Yi Injwa’s Rebellion. As a result, both Kang’s family and his wife’s family were stigmatized as traitors, and he was banished from his government position.

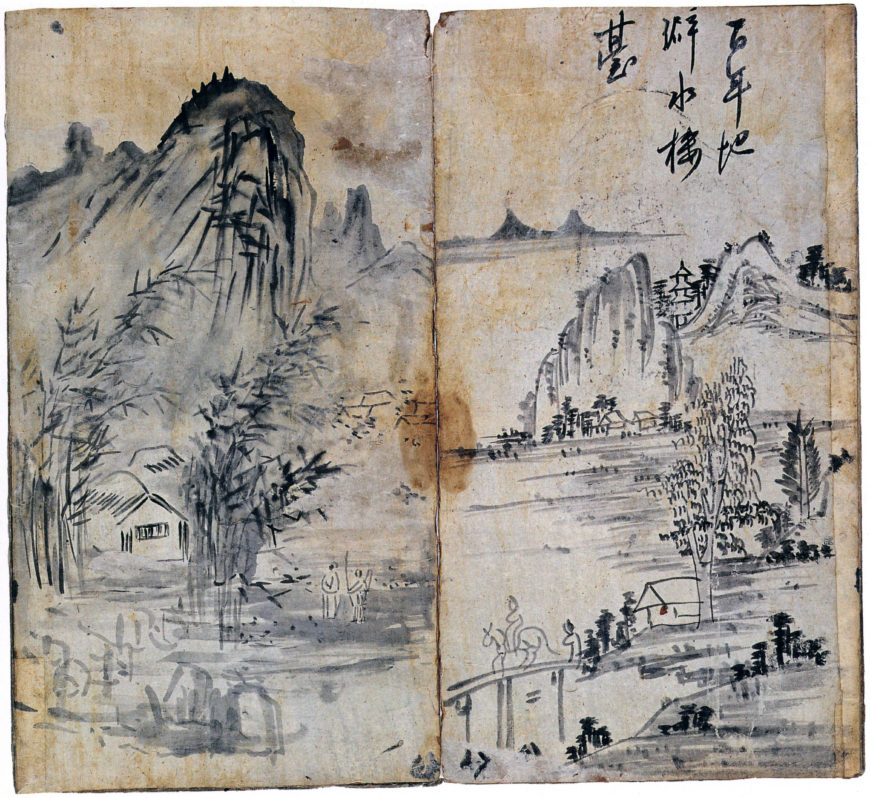

Kang Sehwang, landscape painting on the mounted back of Rules of Calligraphy, Volume 10, 1737, ink on paper, 13.8 x 24.9 cm (private collection; photo: Korea Data Agency)

At the age of twenty-five, with his family facing financial difficulties, Kang Sehwang moved into an empty house owned by his wife’s family near Yeomcheongyo Bridge outside Namdaemun Gate. There he spent long hours in his small study named “Sanhyangjae” (山響齋), appreciating paintings and playing the geomungo (traditional string instrument). He also made his own landscape paintings, which he pasted on the walls. While tuning and playing his geomungo, he was struck with the sense that the noble sounds of the old melodies harmonized naturally with the landscape. Clearly, despite the difficulties of his life, Kang maintained a generous and relaxed atmosphere for art appreciation.

The following poem, written in his youth, provides a glimpse of Kang’s troubled life of isolation, as well as the respite that he found through art:

The sound of rushing water crashing against stones

The sound of a gentle breeze blowing between the pines

The sound of a song sung by fishermen

The sound of an evening bell from a temple on a cliff

The sound of cranes in the forest

The sound of dragons crying in the water

All of these sounds from paintings harmonize perfectly with the sound of my geomungo.

I cannot tell whether the painting is geomungo or the geomungo is painting.

Reaching this level, I forget the illness of body and mind, and feel at ease.

The depression disappears.

In 1743, after the birth of his third son Kang Gwan, Kang Sehwang moved to Ansan, Gyeonggi Province, where his brother-in-law lived. For the next thirty years, he devoted himself to the three arts (i.e., poetry, calligraphy, and painting), as well as music. Fortunately, he was surrounded by many other renowned scholars who were versed in poetry and calligraphy of the past and present, such as his two brothers-in-law, Yim Jeong and Yu Gyeongjong, and friends such as Heo Pil, Yi Subong, Yi Ik, Kang Huieon, Kim Hongdo, and Shin Wi. Kang socialized and communicated with these colleagues through poetry, calligraphy, and painting.

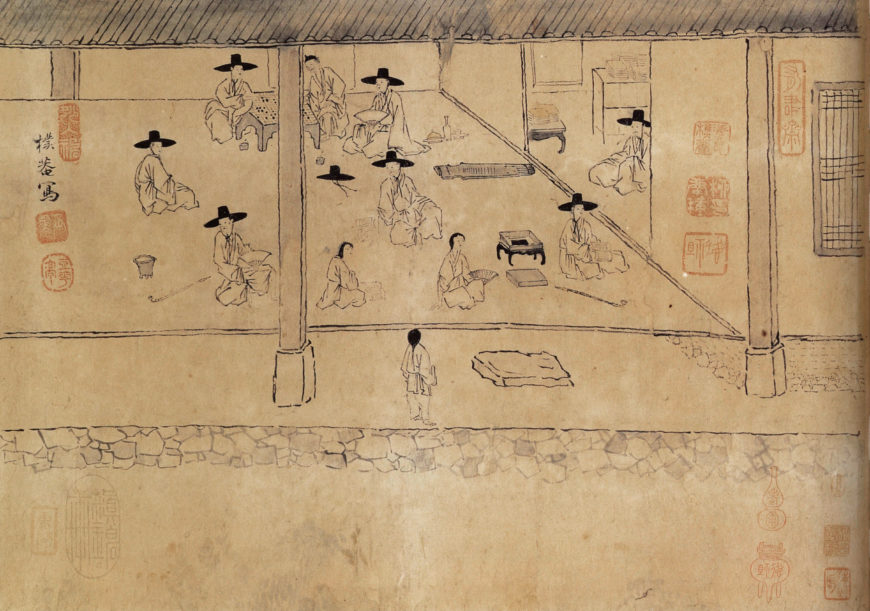

Detail, Kang Sehwang, Gathering in Hyeonjeong Pavilion, 1747, ink on paper (private collection; photo: Korea Data Agency)

Kang visualized one such interaction with his fellow literati scholars in his painting Gathering in Hyeonjeong Pavilion (玄亭勝集圖). In June 1747 (when he was thirty-four years old), Kang and his friends met at Cheongmundang House (聽聞堂) in Hyeongok, Ansan, where they had a festive time enjoying geomungo music, singing songs, and composing poetry. Two of Kang’s sons—Kang In and Kang Wan—can be seen in the painting, along with other relatives such as Yu Gyeongjong, Yu Gyeongyong, and Yu Seong. Kang Sehwang himself is seated next to the geomungo, facing to the right.

Next to this painting, Kang wrote the following poem:

Drinking wine with a clear view of the mountain landscape,

The sound of the geomungo resonates a great distance, along with the wind between the pine trees.

When the hail stops, the sound of tiles being placed on the go board feels cool.

Please don’t refrain yourself from getting drunk with a candle in your hand,

No need to lament the quick passing of time.

Passing the age of forty, Kang wrote that he admired and practiced the three arts not to gain recognition, but simply for his own contentment:

When I am sober, I cannot go mad.

When I am mad, I write a poem.

Once the poem is composed, I write it in cursive script.

The calligraphy also becomes quite peculiar.

I only appreciate and approve it myself,

I do not want others to recognize it.

Kang Sehwang, Self-Portrait, 1782, ink and color on silk, 51 x 88 cm, Treasure 590-1 (National Museum of Korea)

In addition to poetry, Kang Sehwang also immersed himself in painting, becoming adept at portraits, landscapes, and paintings of the “four gracious plants.” His interest in portraiture is evident from the fact that he painted at least six self-portraits before the age of seventy. He treated portraits like paintings of nature, attempting to achieve a precise and faithful likeness of the sitter. Meanwhile, in his landscapes, he sought to convey the intangible spirit and energy of the respective site. He developed an interest in Western-style paintings, and continuously sought to advance his knowledge in calligraphy and painting, even in his golden years.

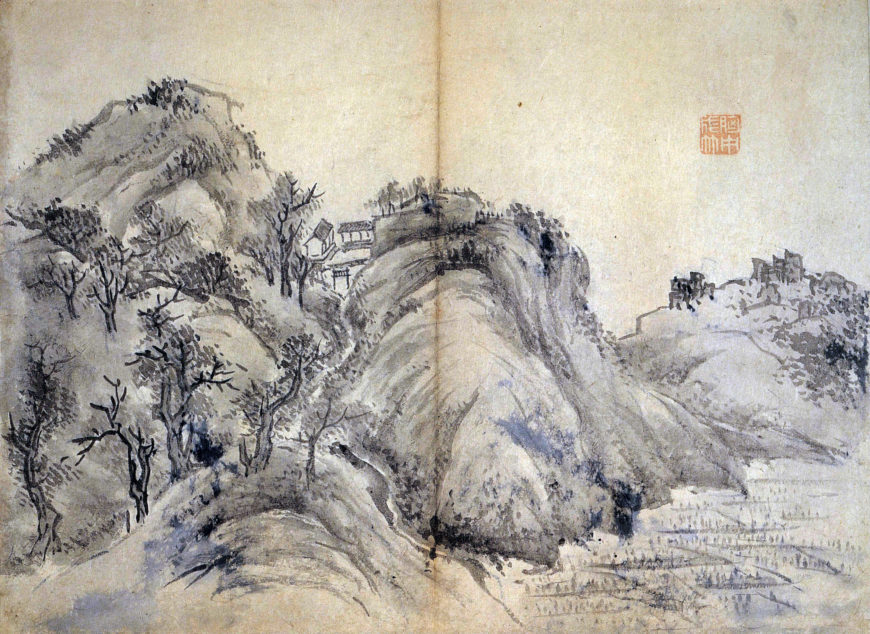

Kang Sehwang, album painting of Mt. Geumgang, 1788, ink on paper, 25.7 x 35 cm (National Museum of Korea; photo: Korea Data Agency)

In 1773, when he was sixty years old, Kang’s life reached a turning point when he accepted a government post from King Yeongjo. He then received awards for receiving the highest score in the civil service examination for seniors (when he was sixty-four years old), and for the highest score in the regular civil service examination (when he was sixty-six). He served in a wide range of government posts, including as the caretaker of King Sejong’s tomb (英陵參奉), the archivist of the Palace Garden Bureau (司圃別提), the third minister of the Ministry of War (兵曹參議), and the chief magistrate of Hanseongbu (漢城府右尹). When he turned seventy-one years old, Kang was inducted into the giroso (耆老所), or “Hall of Elderly Officials,” which honored high-ranking officials over the age of seventy. The next year, at age seventy-two, he traveled as an envoy to Beijing, where he achieved fame for his calligraphy and painting. At the age of seventy-six, he visited Mt. Geumgang, documenting his experience in a travelogue with true-view landscape paintings.

Yi Myeonggi’s Masterpiece: Portrait of Kang Sehwang

Detail, Yi Myeonggi, Portrait of Kang Sehwang, 1783 (Joseon Dynasty), ink and colors on silk, 145.5 x 94 cm, Treasure 590-2 (National Museum of Korea)

Following in his grandfather and father’s footsteps, Kang Sehwang became the third successive generation of his family to be admitted to the giroso (耆老所), Hall of Elderly Officials. In 1783, two months after Kang received this honor, King Jeongjo ordered the young court artist Yi Myeonggi to paint a portrait of Kang Sehwang.

In addition to being revered as the teacher of Kim Hongdo, Kang Sehwang was an esteemed painter in his own right, known especially for his amazingly lifelike portraits. As such, when the time came to paint Kang’s portrait, King Jeongjo knew that he had to choose his best portraitist for the task. At the time, Yi Myeonggi was almost without peer when it came to portraiture. But despite this status, Yi must have felt pressure from the daunting task of meeting and painting the famous artist.

Utilizing both scientific procedures and his own insights, Yi Myeonggi carefully analyzed Kang’s anatomy and facial features. Beyond these surface techniques, Yi’s true genius lay in infusing the portrait with Kang’s internal mind and spirit. With only a brush and palette, the artist was somehow able to capture the maelstrom of desire and emotion that Kang had experienced in his life, from the greatest joy and success to the deepest pain and frustration. Elaborate shading was used to precisely convey the subtle texture of the face, the depth of the eye sockets, the creases around the cheeks and nose, and other concave and convex areas. The detailed complexion and subtle creases, rendered with minute lines and dots, are as real as a photograph of a living person.

Detail, Yi Myeonggi, Portrait of Kang Sehwang, 1783 (Joseon Dynasty), ink and colors on silk, 145.5 x 94 cm, Treasure 590-2 (National Museum of Korea)

Adding to the vivacity is the white beard, which harmonizes perfectly with the rest of the face. Yi’s meticulous attention to detail is epitomized in his depiction of the knuckles on the hand, which peeks out from the right sleeve.

On the upper right, King Jeongjo added his own commentary about the painting, in which he succinctly summarizes the life and character of Kang Sehwang.

His nature encompasses a broad mind, an open heart, refined taste, and an easygoing spirit.

Pushing his brush, he wrote tens of thousands of characters

on folding screens and pieces of patterned paper for the royal court.

Always counted amongst the highest-ranking officials,

his mastery of the three arts (i.e., poetry, calligraphy, and painting) evoked Zheng Qian (鄭虔) of the Tang Dynasty

When he visited China as an envoy,

People from Seoru (西樓) vied to see him.

Knowing how difficult it is to keep people of such talent near me,

All I can do is humbly offer him a meager drink.

[Calligraphy by Jo Yunhyeong]

The production of this portrait was comprehensively described by Kang Gwan (Kang Sehwang’s third son) in the Record on the Portrait of Kang Sehwang (癸秋記事). In addition to a daily log documenting all nineteen days of the portrait’s production, Kang Gwan also left a detailed diary that records the name of the painter and other craftspeople involved, the total cost, the materials, the places where the materials were purchased, an honorarium, and his own review of the painting. With such exhaustive details about how this classic portrait was produced, Kang Gwan’s records are an invaluable document for art historians.

To summarize the details, the painting cost a total of 37 nyang (copper taels), ten of which were paid to the artist Yi Myeonggi. Starting on July 18, Yi spent a total of ten days painting the portrait at Kang Sehwang’s house. The painting was then mounted and a special storage case for it was produced, before the final work was unveiled on August 7.

Yi Myeonggi, Portrait of Kang Sehwang, 1783 (Joseon Dynasty), ink and colors on silk, 145.5 x 94 cm, Treasure 590-2 (National Museum of Korea)

Although some 230 years have now passed since this portrait was painted, its remarkable spirit and unparalleled quality continue to resonate from every angle. With his proper attire and solemn posture, Kang Sehwang is the model of a dignified Joseon official. Like a contemporary photograph, Portrait of Kang Sehwang reveals every detail of the subject. Yi Myeonggi went to great lengths to achieve such realism, concentrating intensely on every tiny dot and stroke. Combining the stern dignity of an Elderly Official with the youthful spirit of a scholar who escaped reality through art, Yi Myeonggi captured the true internal spirit of Kang Sehwang, thus manifesting the principle of “jeonsin” (傳神). Indeed, only a highly skilled portraitist of Yi’s caliber could have created such a masterpiece.

Additional resources

Read this essay and learn more on The National Museum of Korea’s website.