Wat Phra Kaew (also known as the Temple of the Emerald Buddha) is arguably the most important Buddhist temple in Thailand; however, it is not a Buddhist monastery as neither monks nor nuns use the temple complex as their residence or primary place of congregation. Instead, Wat Phra Kaew was once the private chapel to the kings of Thailand and members of the court. Today, like the Grand Palace in Bangkok, Thailand, where the temple complex is located, it is open to the public. The temple or wat was completed in 1783 under the patronage of King Rama I to enshrine the Emerald Buddha (Phra Kaew) for which it was named.

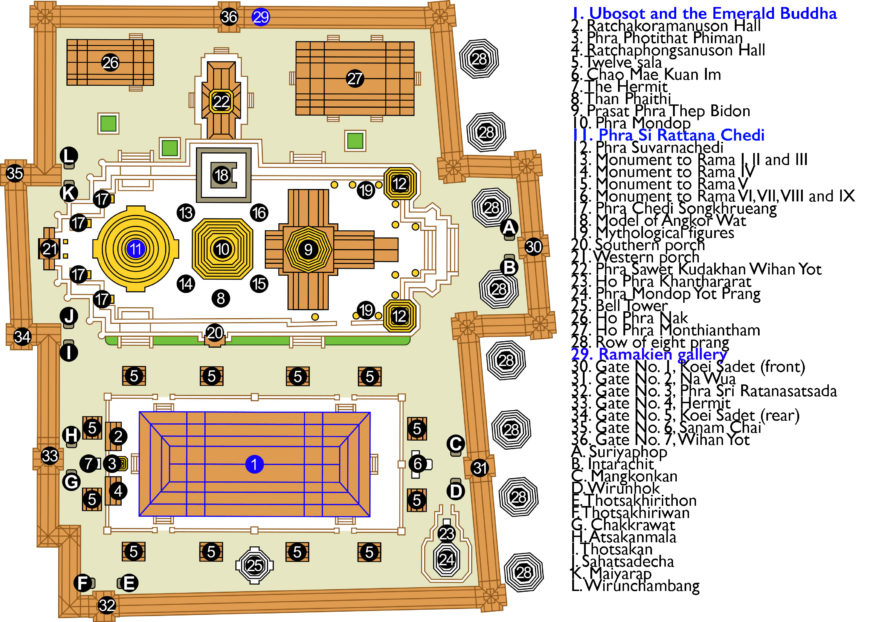

Wat Phra Kaew is not a singular building; instead, it refers to a temple complex that includes a variety of structures. This essay will focus on the ordination hall or ubosot, which is traditionally considered one of the most important structures at a Buddhist temple as well as a gallery of mural paintings that encircles the temple complex.

A home for the Emerald Buddha

Emerald Buddha, 15th century, Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok, Thailand (photo: Sodacan, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Although its name suggests that the Emerald Buddha is carved of emerald, it is likely carved from jadeite that was hewn from the mountains of Northern Thailand or the Shan State of Myanmar. [1] Its name comes from its green color, and descriptions of it in the 15th-century text, the Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha. According to the text, the statue was carved from a wish-granting jewel in the 1st century B.C.E. in heaven; however, more likely is that it was carved in the 15th century C.E. in Northeastern Thailand. [2] The Chronicle is mostly mythological, but it does provide some historical context for the statue and its function as an object of protection. This is because much of the Emerald Buddha’s description in the Chronicle describes its association with the chakravartin or universal world ruler, as well as its enshrinement in various kingdoms in what is today modern Thailand and Laos. By the reign of King Rama I, the legend of the Emerald Buddha had become well known and its stories became actualized as kings fought over the icon and built grand temples to house it.

When King Rama I established his new capital in Bangkok in 1782, he took the Emerald Buddha from the former capital city of Thonburi (on the opposite side of the Chaophraya River from present-day Bangkok). In fact, prior to becoming king, he was a military general for the previous ruler of Thailand, King Taksin. At that time, he captured the Emerald Buddha from Vientiane, Laos, so that King Taksin could claim the icon for himself. When Taksin was dethroned and ritually killed, King Rama I marked his new reign with the enshrinement of the Emerald Buddha in the Grand Palace.

Phra Si Rattana Chedi, a chedi (reliquary mound) covered in gold mosaic tiles (photo: กสิณธร ราชโอรส, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Ordination Hall (ubosot)

Building of the temple complex began in 1782, the same time that King Rama I began construction of his new palatial residence, the Grand Palace. Although many might assume that Wat Phra Kaew refers to just one building, it is an entire complex that includes libraries, chedi or reliquary mounds (in Sanskrit, stupa), as well as assembly halls (in Sanskrit: vihara; in Thai: wiharn) and outdoor sitting pavilions (sala) along with other structures.

One of the first projects undertaken by King Rama I was the construction of the ordination hall (ubosot), which houses the Emerald Buddha, and is used for the ordination of male members of the royal family. It is one of the most ornate structures in the temple complex. The roof of the ordination hall consists of three tiers, which indicates that it is a royally sponsored temple (community temples have a single or double–tiered roof).

The central base of the Ubosot is decorated with a golden row of 112 Garudas, Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok, Thailand (photo: Heinrich Damm, CC BY 2.0)

The building sits on a base constructed of marble and decorated with Chinese porcelain tiles as well as gilded statues of garuda, which appears to lift the entire structure towards heaven.

Detail of glass and gold mosaic, entrance to Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok, Thailand (photo: Aimaimyi, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The exterior of the building is covered entirely in gilding and glass mosaic in a floral motif called kanok, which was used during the Ayutthaya period (1351–1767). Ayutthaya is also a city located roughly 80 kilometers (50 miles) north of Bangkok and was an important center for trade and diplomacy. Later periods, however, remembered Ayutthaya as a golden age after the city’s destruction by the Burmese in 1767, and the subsequent burning of the royal palace and other important monuments. The continued use of the kanok motif was due to its association with fecundity and prosperity as well its association with the arts and architecture of the Ayutthaya period.

One of the pediments of the Ubosot, depicting tVishnu on the back of a garuda, Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok, Thailand (photo: ErwinMeier, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The ordination hall’s pediments are decorated with an intricate gilded image of Vishnu seated atop his mount, Garuda. Although Vishnu is a Hindu deity, he has long been synonymous with kingship in the Southeast Asian region because of stories associated with him as an ideal and just king. The building has been updated throughout the years, but its overall design has remained consistent with King Rama I’s original vision. This is very important to art and architectural historians because the ordination hall was modeled after Wat Phra Sri Sanphet, the royal temple in Ayutthaya, which no longer survives (it was burned down during the Ayutthaya-Burmese War in 1767).

Once reserved for the king and his family and guests, visitors and worshippers alike can now visit the sacred space and admire or pray to the Emerald Buddha. Photography is not allowed inside of the ordination hall in order to preserve the paintings, which can become damaged from flash photography and to be respectful of the Emerald Buddha icon; however, photographs of its interior that have emerged on social media and on the internet demonstrate that this rule is not always followed.

The interior of the ordination hall is just as ornate as its exterior. Every surface of the interior’s walls and ceilings are decorated with painted murals or decorative motifs. The ceiling is painted with red and gold kanok designs as well as being embellished with silver glass mosaic that has been arranged in a star formation to simulate heaven. [3] The four walls of the ordination hall are decorated with paintings narrating the Buddha’s biography as well as depictions of the Buddhist cosmos. Although many of the current mural paintings date to the reign of King Rama III when he oversaw the restoration of the temple complex for the 50th year anniversary of the Chakri Dynasty, they mostly conform in style and content to the reign of King Rama I.

Buddha images inside the ordination hall (ubosot) of Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok, Thailand (photo: Sodacan, CC BY-SA 4.0)

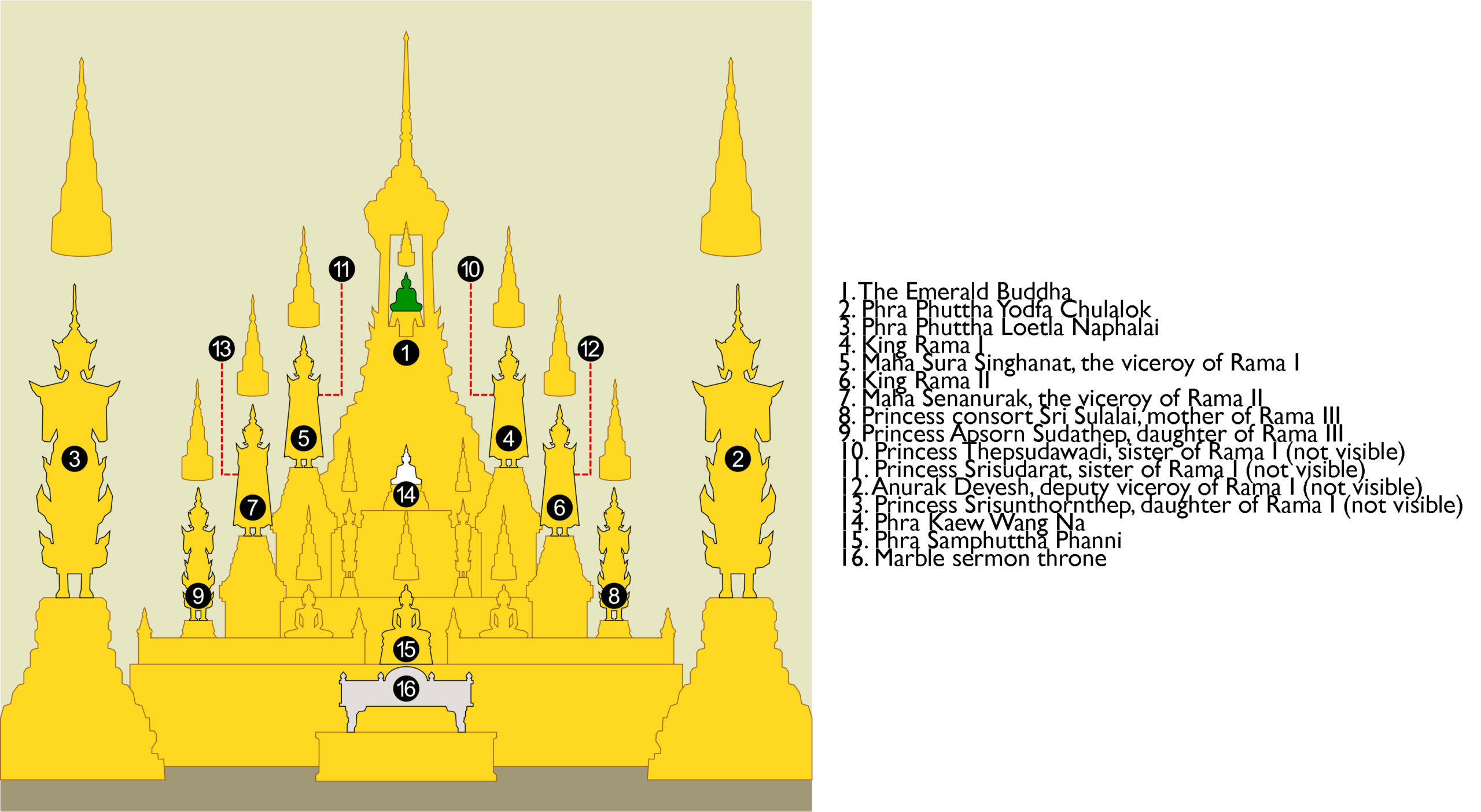

Enshrined in the ordination hall is the Emerald Buddha. The statue itself is rather diminutive in size, and measures 66 centimeters (26 inches) in height; however, it sits on an elaborate multi-tiered gilded throne that magnifies its importance and sacredness to Thai Buddhists. The Emerald Buddha sits directly under a five-tiered prasat that recalls Mt. Meru, the mythical abode of Buddhist deities as well as the center of the Buddhist universe. This type of design was used for both royal and religious architecture in many early Southeast Asian kingdoms, as the king was considered a god. The entire throne is surrounded by a variety of objects, including two large (3 meters; 118 inches) crowned standing images of the Buddha dedicated to Kings Rama I and II (visible in the photograph above), ten standing images of the Buddha dedicated to male and female members of the royal family, in addition to other important Buddhist icons.

Murals of the Ramakien

Wat Phra Kaew’s importance as a Buddhist temple in Thailand owes to its association with the kings of Thailand, but also because it houses the Emerald Buddha statue, which has long been an object that expresses the legitimacy of rulers in this region. It therefore may be a surprise to visitors that the temple is also home to a famous set of mural paintings that depict the Hindu narrative, the Ramayana. This epic tale centers on Prince Rama, an avatar of Vishnu, who is banished from his father’s kingdom of Ayodhya at the request of his stepmother. To avoid creating discord in the kingdom and in his father’s household, Rama leaves Ayodhya and lives in exile with his wife Sita and devoted brother Lakshmana. Much of the story follows Rama through his journeys in which he demonstrates the virtues of duty to one’s family, spouse and kingdom. It is these characteristics that are highlighted in the murals of the Ramakien, the Thai version of the Ramayana that was written by King Rama I and his court poets. In focusing on Rama as an ideal king rather than a Hindu god, the placement of the Ramakien murals around the temple complex makes sense. The kings of the Chakri Dynasty, who adopt the title of Rama for themselves, want to be seen as ideal kings. The placement of the murals outside of the main precinct of the temple rather than at its center ensures that they do not detract from the Buddhist nature of Wat Phra Kaew.

Sita, wife of Rama, was discovered by King Janaka in a furrow in a field. She was raised by the king and his queen. Sita is believed to be the daughter of Mother Earth (Bhumi Devi). Birth of Sita, Ramakien Gallery (detail), Phra Kaew, Bangkok, Thailand (photo: Melody Rod-ari)

There are a total of 178 mural panels that depict various events from the Ramakien, which are accessed via open air galleries that surround the temple complex. The murals begin with the royal births of Rama, his brothers and his future wife Sita. As one walks through the galleries in a counterclockwise fashion, the story unfolds with Rama’s banishment and exile and his war with the Ravana (in Thai, Tosakanth) who abducts Sita. In his effort to save his wife, Rama is aided by the monkey general, Hanuman. The murals end with Rama and Sita’s reunion.

The mural’s exposure to the humid climate of Bangkok has resulted in their being restored or repainted every fifty years. The last major repainting took place in the 1970s in preparation for the Chakri Dynasty’s bicentennial celebration in 1982. Artists of renown at the time, who were trained in the classical arts of Thailand, were chosen to repaint the murals—one such artist is this author’s grandfather, Jamnong Rod-ari. Since this time, the murals continue to be conserved but not repainted.

Today, Wat Phra Kaew stands as an important monument that reflects the best of Thai craftsmanship and artistry since the late 18th century.

Notes:

[1] Carol Stratton. Buddhist Sculpture of Northern Thailand (Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books, 2004), pp. 40, 131.

[2] Melody Rod-ari, “The Origins of the Emerald Buddha,” in Across the South of Asia: Essays in Honor of Robert L. Brown, eds. Robert DeCaroli, Paul Lavy and Bindu Gude (New Delhi: DK Printworld), pp. 298-99.

[3] Naengnoi Suksri, The Grand Palace (Bangkok: Riverbooks, 1998), p. 49.