Large underglaze-painted jar, 14th century (Ming dynasty, Hongwu period, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, southern China) 67.2 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Chinese porcelain decoration: underglaze blue and red

Though Chinese potters developed underglaze red decoration during the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368 C.E.), pottery decorated in underglaze blue was produced in far greater quantities, due to the high demand from Asia and the Islamic countries of the Near and Middle East. Painting with underglaze red was more difficult than underglaze blue: the copper oxide used as the coloring agent was harder to control than the cobalt that was used for the underglaze blue. The firing left parts of the red areas grey, as on this large jar.

The first emperor of the Ming dynasty, which was to rule China for the next 300 years, was the general Zhu Yuanzhang, whose title was Hongwu. He overthrew the Yuan dynasty, whose rulers had been foreigners (Mongols). He was determined to re-establish the dominance of Chinese style at court, and blue-and-white porcelain was produced in designs following Chinese rather than Islamic taste. Similar pieces were executed with underglaze red for use by the emperor.

Hongwu banned foreign trade several times, though this was never fully effective. The import of cobalt was disrupted, however, which resulted in a drop in the production of blue-and-white porcelain. For a short time at the end of the fourteenth century, more wares were decorated with underglaze red than underglaze blue.

Blue-and-white porcelain

The earliest blue-and-white ware found to date are temple vases inscribed 1351. These display a competence which indicate that the underglaze-painting technique was well-established by that time, probably originating in the second quarter of the fourteenth century. Cobalt blue was imported from Iran, probably in cake form. It was ground into a pigment, which was painted directly onto the leather-hard porcelain body. The piece was then glazed and fired. “Blue-and-white” porcelain was used in temples and occasionally in burials within China, but most of the products of the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) appear to have been exported.

Trade remained an essential part of blue-and-white porcelain production in the Ming and Qing dynasties (1644–1911). Europe, Japan and Southeast Asia were important export markets. Vessels, with numerous bands of decoration, were painted with Chinese motifs, such as dragons, waves and floral scrolls. The potters of Jingdezhen also produced wares to satisfy the demands of the Middle Eastern market. Large dishes were densely decorated with geometric patterns inspired by Islamic metalwork or architectural decoration.

Blue-and-white porcelain was particularly admired by the Imperial court, and it is interesting to trace the shapes and motifs preferred by different emperors, many of whom ordered huge quantities of porcelain from the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen.

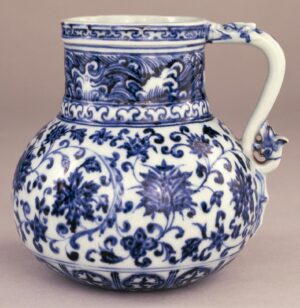

The jug probably had a lid, which has been lost. Blue-and-white porcelain jug, early 15th century (Ming dynasty, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, southern China), 14 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

The blue-and-white wares of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries often took their shapes from Islamic metalwork. The globular body, tall cylindrical neck and dragon handle of this jug all imitate contemporary metalwork of Timurid Persia. The crowded decoration of this jug is a feature of early blue-and-white porcelain that continued into the early part of the Ming dynasty. It is very different to the generally more subtle character of Chinese ornament. The motifs used in decorating the jug, however, are still distinctly Chinese, notably the breaking waves on the neck and floral scroll on the body.

Overglaze enamels

The term “overglaze enamels” is used to describe enamel decoration on the surface of a glaze which has already been fired. Once painted, the piece would be fired a second time, usually at a lower temperature.

The first use of overglaze enameling is found on the slip-covered wares of northern China. This was an innovation of the Jin dynasty, with documented pieces as early as 1201. These were utilitarian wares, not for imperial use. Under the emperors of the Ming (1368–1644) and the Qing (1644–1911) dynasty, the various techniques of overglaze enameling reached their heights at the manufacturing centre in Jingdezhen.

Doucai vase, c. 1723–35 (Qing dynasty, Yongzheng period, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, southern China), 9.5 x 6.8 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

The most highly prized technique is known as doucai (“joined” or “contrasted” colors), first produced under the Ming emperor Xuande, but more usually associated with Chenghua. Cobalt was used under the glaze to paint the outlines and areas of blue wash needed in the design. The piece was then glazed and fired at a high temperature. Overglaze colors were painted on to fill in the design. The piece was then fired again at a lower temperature. The vase above, which dates to the reign of Emperor Yongzheng, is a very good example of the technical perfection in later doucai wares. The main design comprises green, yellow and mauve dragon medallions. The dragons are five-clawed, whose use was restricted to the emperor. Auspicious Buddhist emblems decorate the shoulder of the vase.

New colors (including pink!)

There were also important developments under the Qing dynasty. Famille rose (pink), jaune (yellow), noire (black) and verte (green) were overglaze enamel-decorated porcelains made from the Kangxi period and later.

Butterfly medallion (detail), Famille rose butterfly bowl, c. 1723–35 (Qing dynasty, Yongzheng period, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, southern China), 6.86 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Accordingly to Chinese tradition, butterflies are an auspicious sign. They convey a wish for longevity, and were therefore often used to decorate birthday gifts or lanterns given during the Autumn Moon Festival: on the 15th day of the 8th month of the lunar calendar (usually around September). The Festival is celebrated by lighting lanterns of different shapes, sizes and colors, and by gazing at the moon. The bowl above, made at the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen, may have been presented by the emperor to a family member or worthy subject on such an occasion.

The bowl is decorated in famille rose overglaze enamels. This technique was perfected under the Yongzheng emperor (reigned 1723–1735) and is considered the last major technological breakthrough at the Jingdezhen kilns. The great innovation was the production of the distinctive pink enamel from which the wares take their name. The pink color was provided by adding a very small amount of gold to red pigment. The resulting color was opaque, as were the other famille rose enamels, and so could be mixed to create a wider range of colors than had been possible before.

Additional resources

S.J. Vainker, Chinese pottery and porcelain: From Prehistory to the Present (London: The British Museum Press, 1991).

Regina Krahl and Jessica Harrison-Hall, Chinese Ceramics: Highlights of the Sir Percival David Collection (London: The British Museum Press, 2009).

© The Trustees of the British Museum