Two-sided table screen, dated to the Kangxi period (1662–1722 C.E.), Qing dynasty, glazed porcelain, 39.6 cm high (Victoria and Albert Museum)

In the Chinese porcelain collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A in London), there is an unusual table screen, a traditional decoration on a scholar’s desk. This screen is abundantly decorated in relief on both sides. The patron and the artist remain anonymous, but judging from the screen’s quality, it may have been commissioned by the court and fired in a Jingdezhen kiln. In the long history of the manufacture of table screens in China it is extremely rare to see one made entirely of porcelain and that is fired as a single piece because the size and shape almost certainly result in firing flaws.

Reconstruction of a scholar’s desk from the exhibition, “In Pursuit of Elegance and Simplicity: Chinese Scholars’ Studio Furniture from the Tseng Collection“

Table screen, 18th century, ivory, 26.3 x 12.3 cm (The British Museum)

What is a table screen?

Table screens ennoble the elegant studio of a scholar. They generally rested on a corner of the scholar’s working desk for decoration purposes and were generally made of two parts: a two-side decorated rectangular panel sitting and a holding stand. Moreover, as one of the most significant scholar’s objects representing intellectual curiosity and aesthetic taste, a variety of precious materials, such as lacquer, cloisonné, gilt-bronze, jade, and valuable hardwoods, were used in crafting Chinese table screens. Among them, the table screen made of ivory was one of the most sought-after types due to the rarity of the material and the technical prowess of carvings. It is intriguing to find that the glazed surface of the V&A table screen resembles treated ivory in many ways—such as the milky white monochrome color and the light grey crackled traces.

An unusual subject

One side of the porcelain table screen is decorated with geese and lotus, which in turn are framed by squirrels, grapes, and vines.

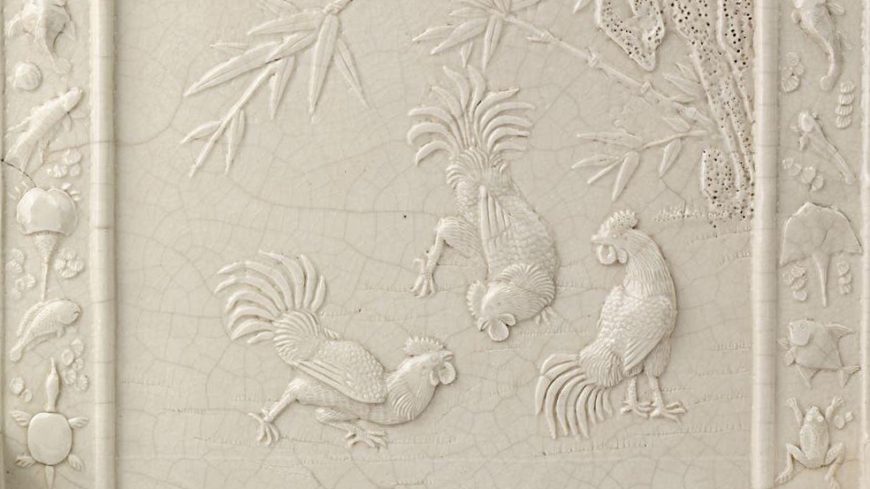

The other side displays three roosters and bamboo as the central imagery, and on the decorative frame we find sea creatures swimming through algae, seaweed, and duckweed. The animals depicted include a horseshoe crab, an eel, a coral-reef snake, a tortoise, a frog, a stingray, an alligator gar, a squid, a sogliola, a grass goby, and various kinds of conches and many others. Interestingly, some species of marine life depicted here do not originate in China.

Detail, table screen, dated to the Kangxi period (1662–1722 C.E.) of the Qing dynasty, glazed porcelain, 39.6 cm high (Victoria and Albert Museum)

The subjects we see on table screens are consistently something auspicious. For example, one of the central images on the V&A table screen depicts three roosters in front of bamboo and a taihu rock, which are perceived to have moral qualities analogous to scholars’ cultural and ethical virtues in Confucianism. For example, the process of taihu rock’s formation has been compared with scholar’s strength and endurance. And the rooster, pronounced “ji” in Chinese, is a homophone for prosperity and fortune, while “three” stands for multitude in classical Chinese.

Mirror with birds and beasts amid grape vines, 7th–8th century (Tang dynasty), bronze, China, 17.1 cm in diameter (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The moulded pattern of grapes and vines and squirrels decorating the frame of one side is also similar to a Tang dynasty bronze mirror. This particular pattern has non-Chinese origins from Inner Eurasia and Inner Asia, which was may have been introduced to China through the Silk Road and would have been considered “exotic” in Chinese decorative arts. The pattern of grapes, vines and squirrels in relief is unique to Tang bronze mirrors and rarely being seen on other works of art.

The visual representation of sea creatures that we see on the V&A table screen is highly unusual in Chinese decorative arts during and before the Kangxi period (1662–1722 C.E., during the Qing dynasty). In addition, unlike other elements seen on the table screen, the sea creatures do not have symbolic meaning in Chinese culture and do not appear to fit into the aesthetic of Confucian tradition. So where did they come from?

Bernard Palissy (attributed to), Oval Basin, c. 1550–50, lead-glazed earthenware (Louvre)

Surprisingly, the “exotic” sea creatures seen on the Chinese table screen resemble the glazed rustic-style plates designed by the French potter and natural philosopher Bernard Palissy. If we compare the table screen with an oval basin by Palissy, we can see that the sea creatures seem to correspond to each other. In fact, we can understand the table screen as a late imperial Chinese version of “Palissy ware”—a transcultural object that demonstrates a Chinese work of art in the style of French earthenware. Art historians refer to this as a européenerie—East Asian art that adopted elements and aesthetic designs (sometimes including materials) from from European artworks (here the sea creatures).

Trompe l’oeil porcelain and Européenerie

Imitation bullmouth shell, porcelain, Qing dynasty (The Palace Museum)

The V&A table screen is considered one of the earliest trompe l’œil[/simple_tooltip] porcelains fired in this particular period. Here, the term trompe l’œil porcelain refers to porcelain made or decorated in imitation of other materials, an artistic and scientific tour de force of ceramic design that flourished and reached its zenith of production in China during the so-called High Qing era (c. 1683–1839 C.E.). In this example, the screen is porcelain but resembles ivory. We can compare this process of imitation to another trompe l’œil porcelains, such as a pair of imitation bullmouth shells (Cypraecassis rufa, also commonly known as the red helmet shell). The bullmouth shell could be sourced off the southern African coast of northern KwaZulu-Natal and Mozambique and was a common colonial commodity in the European market for use in decorative art. There was no native source for acquiring bullmouth shell in eighteenth-century China, which make the Qing imitation bullmouth-shell porcelains another example of a européenerie object.

The européenerie style in Chinese art often included trompe l’œil. The interpretation and imitation of European artistic traditions is closely bound with the Qing trompe l’œil porcelain since the genre entered the repertoire of the Jingdezhen porcelain manufactory. In the High Qing period, China experienced frequent encounters with the West, through both European Jesuits and diplomatic missions. The tributes from Jesuits and gifts brought to the imperial court by diplomats became sought-after luxuries because of the rarity of these works of art and the emperor’s preference for them. As a result, they became popular objects of emulation for Qing potters.

Representing transculturalism in trompe l’oeil

The Kangxi period table screen has been seen as a Chinese decorative art of “bizarreness” (qi 奇), a non-canonical design imitating European pottery and bearing a trompe l’œil surface. Accordingly, the V&A table screen, through its eclectic representation and design, epitomizes the High Qing era’s passion in pursuit of transculturalism.

Additional resources

Learn more about the art of the Qing dynasty in a Reframing Art History textbook chapter

John R. Finlay, “Europeaneries: European Exoticism in the Qing Imperial Court, 1644–1911,” presented at the Annual Meeting of the Florida Snuff Bottle Collectors Society, St. Petersburg, Florida, April 24, 1999.

Kristina Kleutghen, “Chinese Occidenterie: The Diversity of ‘Western’ Objects in Eighteenth-Century China,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 47, no. 2 (2014): pp. 117–35.