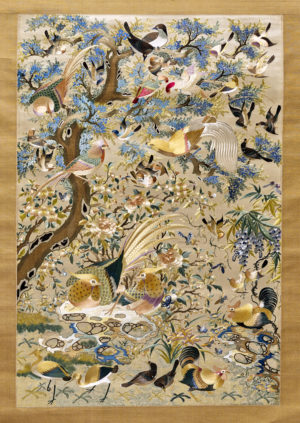

Detail of “One Hundred Birds” Hanging scroll, China, 19th century, white silk satin with polychrome silk embroidery, 109.5 x 72.9 cm (Yale University Gallery)

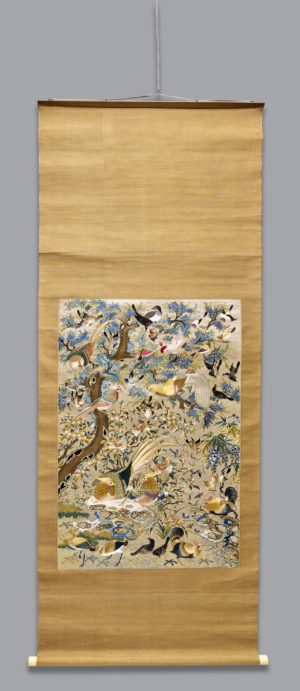

“One Hundred Birds” Hanging scroll, China, 19th century, white silk satin with polychrome silk embroidery, 109.5 x 72.9 cm (Yale University Gallery)

This embroidered hanging scroll, depicting a scene known as “One Hundred Birds” (Bainiao tu 百鸟图), is a stunning example of Guangdong embroidery (also known as Yue embroidery Yuexiu 粤绣): filled with naturalistically depicted birds, animals, and plants, and worked in a rich range of stitches. It displays some of the most characteristic features of this handicraft tradition: densely filled designs; surface complexity created through varied stitches (like long and short alternating stitches, knot stitch, and stitches simulating fur and feathers). The palette is also characteristic with its use of warm and mellow golden browns, beiges, and creams to render the tree and birds, contrasted with blue shades which highlight and bring depth to the forms. Dimensionality was also achieved in Guangdong embroidery through the application of couched metallic thread (Dingjin xiu 钉金绣), sometimes with raised relief effects, or the addition of unusual materials like pearls or peacock feathers.

Together with the popular subject matter dominated by bird and flower designs, these features made this regional embroidery style renowned in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This particular example is embroidered with silk thread on a base of silk satin, and it is mounted like a hanging scroll painting: vertically oriented and framed by a different silk cloth. Such scenes were also sometimes framed in wood and placed on tables as room décor.

“One Hundred Birds” was a common subject matter in art from the Guangzhou region, popular for its celebration of nature and its auspicious meaning. Sometimes known as the “Hundred Birds paying court to the Phoenix” (Bainiao chao feng 百鸟朝凤), the phrase carries the meaning of “Peace under a wise ruler,” since the central phoenix is considered the king of the birds and hence a symbol of the emperor. [1]

Detail, “One Hundred Birds” Hanging scroll, China, 19th century, White silk satin with polychrome silk embroidery, 109.5 x 72.9 cm (Yale University Gallery)

Despite the title, fewer than 100 birds are represented (the title functions figuratively to convey the idea of a large number). The birds depicted include the crane, a symbol of longevity; the pheasant, a symbol of wealth and good wishes; and mandarin ducks, a symbol of marital happiness. Most are paired, a common feature of Chinese visual depictions of birds and animals, and a nod to the importance of balancing male and female to create harmony and unity. There are also many different flowers, including the peony, a symbol of summer and wealth, as well as irises, wisteria, and lots of butterflies. In sum, the scene conveys ideas of seasonal harmony and good fortune, and it demonstrates the complex arrangements of auspicious motifs that developed during the Ming and Qing dynasties. But this hanging also has much to tell us about the development of both artistic and commercial embroidery through the late imperial period.

Detail of the lower portion of the embroidered panel, “One Hundred Birds” Hanging scroll, China, 19th century, white silk satin with polychrome silk embroidery, 109.5 x 72.9 cm (Yale University Gallery)

Embroidery as art

Silk embroidery has long been associated with Chinese culture. Archaeological remnants of embroidery have been found adhered to Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1100 B.C.E.) bronze vessels, and the strong fine silk thread, a natural fiber made by silkworms, made it perfect for producing pictorial and decorative motifs. The chain stitch was largely replaced by the satin stitch during the Tang dynasty (618–907 C.E.), in part because of its ability to depict figural forms used in the representation of Buddhist themes. Fine art embroidery began to flourish in the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127 C.E.), when a court workshop was established to produce embroidered articles for imperial use.

Emperor Huizong, Finches and bamboo, early 12th century, Northern Song dynasty, handscroll; ink and color on silk, China, 33.7 × 55.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In the Song Dynasty, textile artists, including embroiderers and tapestry (kesi 刻丝) makers, began to reproduce the bird-and-flower motifs that had become popular among painters, using a broad range of stitches to create stunning effects of color and texture. [2] Their creations were greatly admired, and embroidery began to be collected as an art form, even as part of the imperial collections.

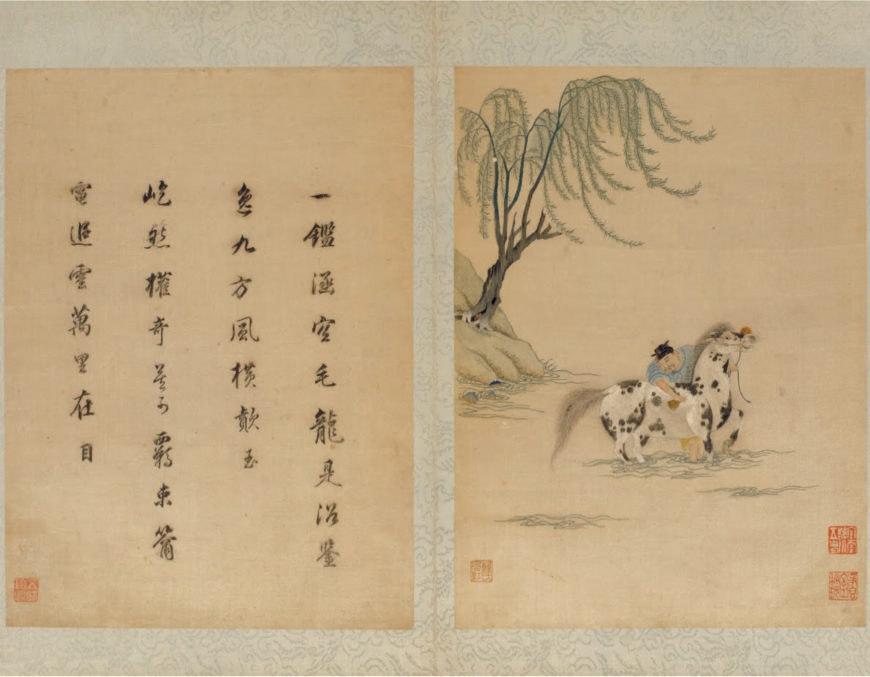

“Washing a Horse (Xima tu),” Gu-Family Embroidery of “Masterpieces of the Song and Yuan Dynasties” by Han Ximeng, Chongzhen reign (1628–44), Ming dynasty (1368–1644), 33.4 x 24.5 cm (The Palace Museum, Beijing, China)

The artistic associations of embroidery continued to develop during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Most notably, the women of the Shanghai-based Gu family became famous for reproducing (sometimes directly, sometimes inspired by) the imagery and stitchwork of the Song dynasty classic painted works to create fine needlework painting (hua xiu 画绣). Their work, known as Gu embroidery (Gu xiu 顾绣), established a connection between fine embroidery and the educated, cultured gentlewomen of literati families, furthering the genteel associations of artistic needlework. [3]

Developments in dye technology during this period meant embroiderers could select from a rich array of colors, and by splitting the thread to create finer strands, and by using variants of satin stitch to subtly tint areas of color, embroiderers could achieve effects akin to painting. As Ding Pei, a mid-Qing embroiderer and author of an 1821 guide to embroidery, Embroidery Treatise (Xiupu 绣谱) put it:

The needle is your writing brush; the length of silk your paper; the floss your ink.Ding Pei

Detail of the upper portion of the embroidered panel, “One Hundred Birds” Hanging scroll, China, 19th century, white silk satin with polychrome silk embroidery, 109.5 x 72.9 cm (Yale University Gallery)

Embroidery as commerce

During the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the artistic style that had been popularized by the Gu women spread further in Jiangnan, the region of wealthy silk and cotton districts, and commercial embroidery shops became more common. The embroidery of this region became known as Suzhou or Su embroidery (Suxiu 苏绣), and as embroidery became more popular over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, other regional embroidery styles also emerged elsewhere in China, including Guangdong or Yue embroidery (Yuexiu 粤绣), Sichuan or Shu embroidery (Shuxiu 蜀绣), and Hunan or Xiang embroidery (Xiangxiu 湘绣). In the twentieth century, the four were grouped together as the “Four Famous Embroidery Styles” (Sida mingxiu 四大名绣), but Guangdong embroidery differed from these other regional styles in two respects.

Firstly, during the nineteenth century, many of the embroiderers were men from Guangzhou and Chaozhou and the craft appears to have been mainly produced in male-staffed workshops, though some of the work was likely subcontracted out to female workers in surrounding villages in the Pearl River Delta region. Even though Chinese embroidery has often been gendered as a female handicraft practice, this scroll was likely embroidered by a team of male embroiderers working in one of the many Guangzhou workshops producing fine hangings and furnishings for domestic and export markets during the nineteenth century.

Secondly, since some embroidery was exported to Europe and America during the Qing period, it developed under the stimulus of Western markets. During the Canton Trade era (c. 1760–1842), European merchants were restricted to the port of Canton (Guangzhou), and only permitted to trade with a small number of licensed merchants known as the Hong merchants. American merchants joined after 1784 and a flourishing trade developed between China and America, particularly in cities like Salem and Philadelphia. The mainstay of the trade was commodities like tea, silk, nankeen cottons and furs, but embroidered garments and furnishings were also collected, and many American museum collections contain examples of shawls, waistcoats, bedspreads and gowns embroidered in Canton.

However, this hanging tells us more about American collecting of Chinese art later in the century. Following the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, which ended the first Opium War, China was forced to open up four other treaty ports: Hong Kong, Shanghai, Amoy, Fuzhou, and Ningbo, and this dramatically changed foreign trade bringing in a flood of European and American manufacture to Chinese markets. During this time, travel times were also much reduced, by the introduction of tea clipper ships and steam-powered vessels in the mid-nineteenth century. The numerous World Exhibitions of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries also brought larger audiences into contact with Chinese art and design, and increased the numbers of tourist visitors eager to collect silk objects. The donor of this object to the museum, Mrs. Moore, was the widow of industrialist William Henry Moore, and a prominent female collector from New York. Her husband had hated to travel, but after his death, she became a keen tourist and collector, especially of Asian art. This object was likely purchased in China in the 1920s and she later donated it to Yale University in 1937.

Notes:

[1] The phrase seems to come from a line from Li Fangdeng李昉等, Taiping yulan太平御览, juan 915, “Tang history (Tang shu唐书).

[2] Alexandra Tunstall has written on kesi tapestries of the Song and their relationship to paintings, “Beyond Categorization: Zhu Kerou’s Tapestry Painting Butterfly and Camellia,” EASTM 36 (2012), pp. 39–76.

[3] While the Gu women popularized the idea that educated elite women could or should produce embroidery with artistic value, this style of embroidery was then more widely commercially produced by the embroidery workshops, which employed both men and women. In the Guangdong region, it appears that it was customary to only employ men in the workshops; elsewhere much less is known about the gendering of workshop production, but home-based women embroiderers are known to have worked for the workshops in Suzhou. Ifen Huang, “Gender, Technical Innovation, and Gu Family Embroidery in Late-Ming Shanghai,” East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine no. 12 (2012).

Additional resources

Carl L Crossman, The Decorative Arts of the China Trade: Paintings, Furnishings and Exotic Curiosities (Pyne Press, 1972)

Dieter Kuhn (ed.). Chinese Silks (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2012)

Rachel Silberstein, A Fashionable Century: Textiles as Art and Commerce in Nineteenth-Century China (Seattle: University of Washington, 2020)

Shelagh Vainker, Chinese Silk: A Cultural History (London: British Museum Publications, 2004)

Verity Wilson, Chinese Textiles (Victoria and Albert Museum 2005)