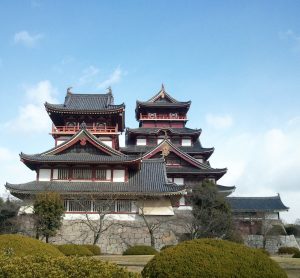

Reconstruction of main keep of Azuchi Castle (Ise Azuchi-Momoyama Bunka Mura, image: Wikimedia Commons)

Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1615): palatial opulence, bold expression, and the beauty of the imperfect

The Azuchi-Momoyama period gets its name from the opulent residences of two warlords who attempted to unify Japan at the end of the Sengoku (“warring states”) era, namely Oda Nobunaga’s Azuchi Castle and Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Fushimi or Momoyama Castle. Both castles were not only martial structures for strategic warfare and defense, but also luxurious mansions meant to impress and intimidate political rivals. The architectural style of these residences derived from that of the pavilions built by Ashikaga shōguns during the previous historical period. Also, both castles’ locations were carefully selected for their optimal proximity to the capital—Nobunaga’s castle was built just outside of Kyoto on the shores of lake Biwa, while Hideyoshi’s was in Kyoto itself, in the southeastern ward of Fushimi.

That the two castles were built only 20 years apart reveals the rapid succession of consequential political events that defined the Momoyama period: Oda Nobunaga rose to power starting in 1560 and by 1582, when he was betrayed by his own retainers, he had managed to gain control of most of Japan’s main island of Honshū.

Fushimi-Momoyama castle, built 1594, rebuilt 1964 (Fushimi Ward, Kyoto, image: Wikimedia Commons)

Nobunaga’s warrior, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, succeeded him and used his strategic thinking and negotiation skills to continue the efforts of unification, besides twice invading Korea (in 1592 and 1597). He was succeeded by another former retainer of Oda Nobunaga, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who managed to secure unprecedented power in 1600, winning the most important of Japanese feudal battles, that of Sekigahara.

Only three years later, Tokugawa Ieyasu was appointed shōgun by the emperor and spent the remainder of his years consolidating the Tokugawa shōgunate, which would become a 250-year rule of relative peace and prosperity. Only forty years had passed from Nobunaga’s ascension to power to Ieyasu’s appointment as shōgun, but these were years filled with momentous change.

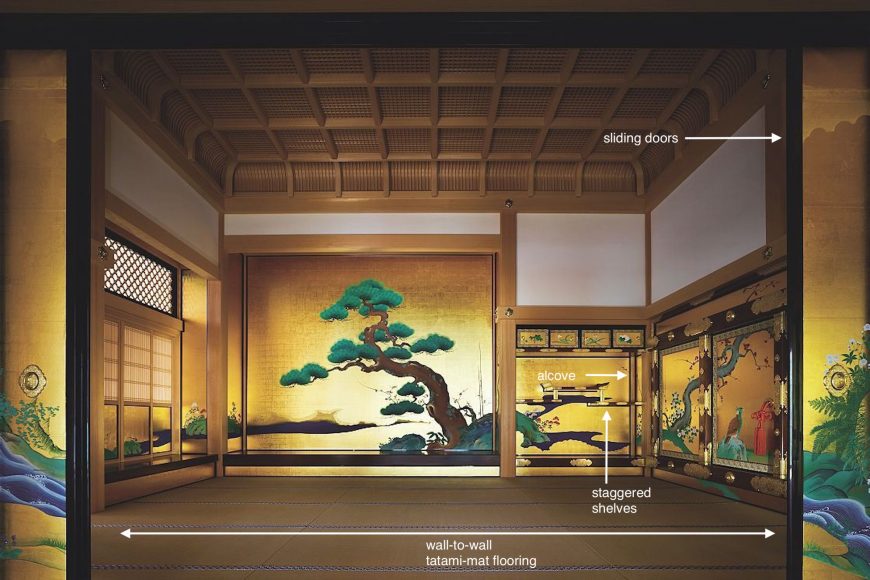

Like other opulent residences of its time, the Azuchi castle comprised numerous buildings in the shoin 書院 architectural style, developed in the Momoyama period. This style entailed a main area flanked by aisles, wall-to-wall tatami-mat flooring, square pillars, and various types of sliding doors and walls that partitioned and reconfigured space. Shoin also featured an alcove in the reception room, known as tokonoma, and elements developed in the Muromachi period for shogunal residences such as staggered shelves and a built-in desk.

Jodan-no-ma (feudal lord’s audience chamber), Honmaru Palace, Nagoya Castle, first built 1615 for Tokugawa Ieyasu’s son, reconstructed 2009-18 (image adapted from: japan-guide)

Kano Eitoku, Chinese lions, 16th century, six-fold screen, color and gold on paper, 223.6×451.8 (Sannomaru, Imperial Household Agency, Japan)

In addition to displaying the power of their owners, Nobunaga’s and Hideyoshi’s castles featured the bold and expressive art that characterized the Momoyama period, perhaps mirroring the energy and courage of the era’s military leaders.

Nobunaga’s Azuchi castle was adorned with the highly expressive paintings of Kanō Eitoku, the grandson of Motonobu, the Kanō painter who established the synthetic Chinese-Japanese aesthetic of the shōgun-patronized school. The very few surviving paintings of Eitoku exemplify this painter’s innovative approach to painting, characterized by dynamic compositions, bold and expressive brushwork, oversized animals, and imagery drawn from nature but set against an opulent golden background that would shimmer in the relatively dark interiors of the warlords’ residences. It can be said that Eitoku’s style matched the power that the painter’s patrons had and wished to put on display.

Hasegawa Tōhaku, Pine trees, 16th century, ink on paper, pair of six-fold screens, 156.8 x 356 cm (Tokyo National Museum)

A rival of the Kanō school emerged in the person of Hasegawa Tōhaku, who may have studied both with Kanō painters and with a pupil of Muromachi-period ink master Sesshū. Tōhaku eventually claimed to be a descendant of Sesshū and developed a bold and highly expressive style, working typically in monochrome ink. His ties to influential tea masters and Zen teachers helped him secure important commissions. Another artist who received major commissions, alongside Kanō Eitoku and Hasegawa Tōhaku, was Kaihō Yūshō, whose military experience and Zen Buddhist training influenced his unique brand of highly charged compositions combining dramatic ink washes and unusually long brushstrokes.

Kaihō Yūshō, Dragons and clouds, 1599, ink on paper (Ken’ninji, Kyoto, image: Japan Times)

Clog-shaped tea bowl with plum-blossom motifs and geometric patterns, early 17th century, stoneware with iron-black glaze, Mino ware, black Oribe type, 7.6 x 14.3 cm, diameter of foot 5.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

At the intersection of impressive palatial architecture and powerful ink paintings was another art form, nascent in the Muromachi period—the tea ceremony or chanoyu 茶の湯. In the second half of the 16th century, the tea master Sen no Rikyū revolutionized the practice of tea by modeling it on wabi, an aesthetic concept closely related to that of sabi. Wabi refers to finding beauty in simple, even humble things. Embracing the spirit of wabi and sabi, a disciple of Sen no Rikyū, Furuta Oribe, actively supported a new type of local ceramics that became so intertwined with Oribe’s style and efforts that they came to be known as Oribe ware. These new ceramics were radically different in a number of ways. First, they were locally produced and became popular enough to compete with Chinese ceramics in the aesthetic hierarchies of tea masters. Second, they are characterized by a distinctive practice of intentionally distorting the shapes of the vessels in response to the wabi aesthetic that valued the imperfect.

The Momoyama period is also remembered for intensified contact with other cultures. Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch ships landed in the Southern island of Kyushu and brought to Japan previously unknown markets, objects, and concepts; firearms, for example, were introduced by the Portuguese as early as 1543. International trade and the spread of Christianity were regarded with suspicion and therefore short-lived, culminating in the self-isolation policy instituted by the Tokugawa. However, trade continued with the Chinese and the Dutch, and a small number of Christians continued to practice in secret.

Nanban folding screen (one of a pair), Arrival of the Europeans, first quarter of the 17th century, ink, color, and gold on paper, 105.1 × 260.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Despite its brevity and limitations, the late 16th-century encounter with Europeans had a lasting influence. In the port of Nagasaki, Japanese artists were able to observe the foreign visitors’ dress, manners, and habits, and a new painting genre emerged, the so-called nanban (literally, “Southern barbarians,” the name given in Japan to the Europeans who arrived from India via a Southern sea route). Nanban paintings depict not only European priests and traders, but also Goanese sailors, who traveled with the merchants and missionaries, and even Caucasian women, although there were no women among those who landed in Japan at the time. Nanban screens became very popular and many copies were made, increasingly more removed from first-hand observations and reliant upon the painters’ imagination.

Writing box with Nanban figures, 1633, black lacquer with gold and silver maki-e, polychrome lacquer, and gold and silver foil inlay, 4.76 × 22.23 × 20.96 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Nanban imagery was not confined to painted folding screens; we encounter nanban motifs in other mediums such as ceramics and lacquerware. The inside of the writing box shown here presents images of Portuguese and Indian or African figures, while the outside is decorated with traditional Japanese motifs of fallen cherry blossoms. Objects such as this writing box exemplify not only the integration of nanban imagery in Japanese visual culture, but also an important Japanese aesthetic principle, that of kazari. Translated as both “ornament” and “the act of decoration,” kazari is also a mode of display—and so much more than that. Above all, kazari is an organizing principle of aesthetic and social dimensions that seeks visually and conceptually stimulating juxtapositions that transform the appearance of both objects and spaces, activating the viewer’s own creativity and imagination.