Dong Qichang 董其昌, Landscape, Ming dynasty, China, 95.5 x 41 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

The hanging scroll

Chinese paintings are usually created in ink on paper and then mounted on silk. This is done using different formats including hanging scrolls, handscrolls, album leaves, and fan paintings.

Hanging scrolls are typically used for vertical compositions. They are hung for display using a cord, which is attached to a thin wooden strip along the top of the silk mounting. There is a wooden rod at the bottom which provides the necessary weight for the painting to hang smoothly. It is also useful when the painting is rolled up for storage.

This example of a hanging scroll by Dong Qichang shows a clear structure. It is divided into a foreground, with four mountain areas in the middle and background as well as sub-divisions. The viewer’s eye is drawn upwards from the foreground to the top peak. The lines of trees and the ink dots showing vegetation mark the contours of the landscape.

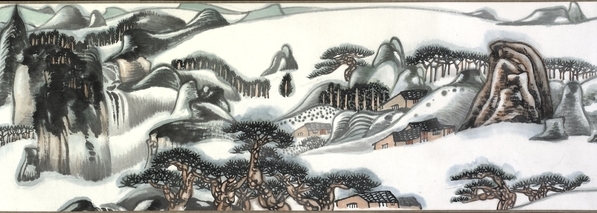

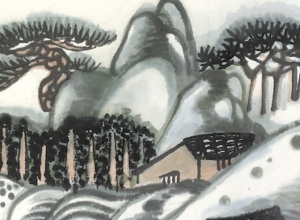

Zhu Xiuli, Landscape, c. 1985–89, handscroll, ink and colour on paper, 30.3 cm high, China (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The handscroll

Detail, Zhu Xiuli, Landscape, c. 1985–89, handscroll, ink and colour on paper, 30.3 cm high, China (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Paintings in China are not usually hung on walls, permanently on display. They are often mounted as handscrolls, rolled up and only brought out for special viewings. This is partly due to the delicate nature of the ink and color, which would fade if left exposed to light for a long time. The unrolling of a scroll is an act of some ceremony. Connoisseurs do not view the painting from a distance, as in the West, but approach close to ‘read the painting’.

Handscrolls are designed to be unrolled, from right to left, revealing one scene at a time. As each new section is unrolled, the previous scene is rolled up, giving the viewer the feeling of a journey through the landscape.

In this handscroll, Zhu Xiuli reinterprets tradition with his twentieth-century version of a traditional landscape. The various elements are organized and controlled, with movement provided by the lines of trees flowing through the scroll. Zhu’s painting is fresh and his use of color washes accomplished.

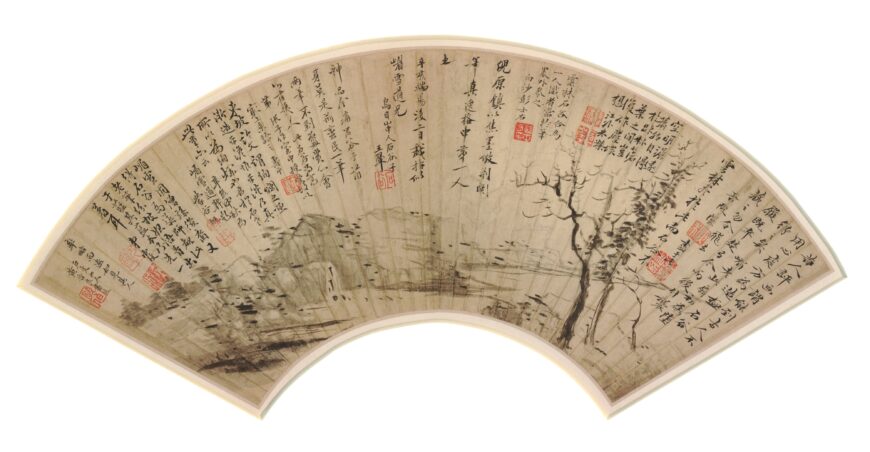

Wang Hui 王翬, Landscape in the style of Ni Zan, fan, 1671, Qing dynasty, paint on paper, China, 48.5 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

The fan

Chinese fans are often decorated with landscapes. Two types of fan are used: the first is nearly circular and made of stiffened silk mounted on a bamboo stick. The second type is curved and folding, made of paper mounted between thin bamboo sticks. This folding type was introduced to Europe from China.

Fan paintings were often created as gifts for a particular occasion and many are dated. Their size made them ideal as presents. Many also include calligraphic inscriptions from friends and comments on the painting.

Although this painting is by the artist Wang Hui, the influence of Ni Zan (1301–74) is clear. The clump of trees, the empty pavilion in the foreground and the horizontal strokes and ink dots depicting the mountains are all typical of the Yuan master. In fact, Wang Hui comments: ‘All of Ni Zan but not all of Wang Hui is contained in this’.

Wang Hui was one of a group of painters known as the Four Wangs: orthodox masters of the early Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). The others were Wang Shimin, Wang Jian and Wang Yuanqi. Most of the calligraphy covering this fan consists of inscriptions by Wang Hui’s contemporaries.

The album leaf

In China, the album format is more intimate than the hanging scroll or handscroll formats. Chinese painting albums usually consist of up to twelve folded pages, with wood or brocade-covered card covers.

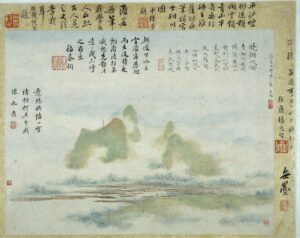

Hu Yukun 胡玉昆, Landscape in “boneless” style, mid-17th century, an album leaf painting, China (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The albums are relatively small, up to 120 square cm, and often include paintings as well as calligraphy. The paintings and calligraphy usually work together, sometimes with a poem on one page and a small painting illustrating it on a facing page. The paintings might be by one artist or a group of different artists, who perhaps joined together to dedicate their works to a friend for a special occasion.

In this album leaf, the artist uses color wash only, with no ink and no outline. This technique is usually used on flower paintings and its use in a landscape gives an other-worldly quality to the scene. Many well-known writers have inscribed the album leaf and on the right-hand margin is the simple comment ‘no ink’.

© Trustees of the British Museum