Statue of Abraham Lincoln in Portland, Oregon, toppled during the Indigenous Peoples Day of Rage on October 11, 2020. George Fite Waters, Abraham Lincoln, 1927, bronze, 10 feet high, photo © Sergio Olmos

On October 11, 2020, protesters in Portland, Oregon, toppled a statue of Abraham Lincoln, spray painting its hands blood red and its plinth with reminders of Lincoln’s role in suppressing Indigenous peoples: “LAND BACK,” a protester scrawled on one side of the stone marker, connecting Lincoln with the accelerated dispossession of Native lands that occurred during and after the Civil War, and “DAKOTA 38” on another side, referencing the mass execution of Dakota men that Lincoln ordered in 1862.

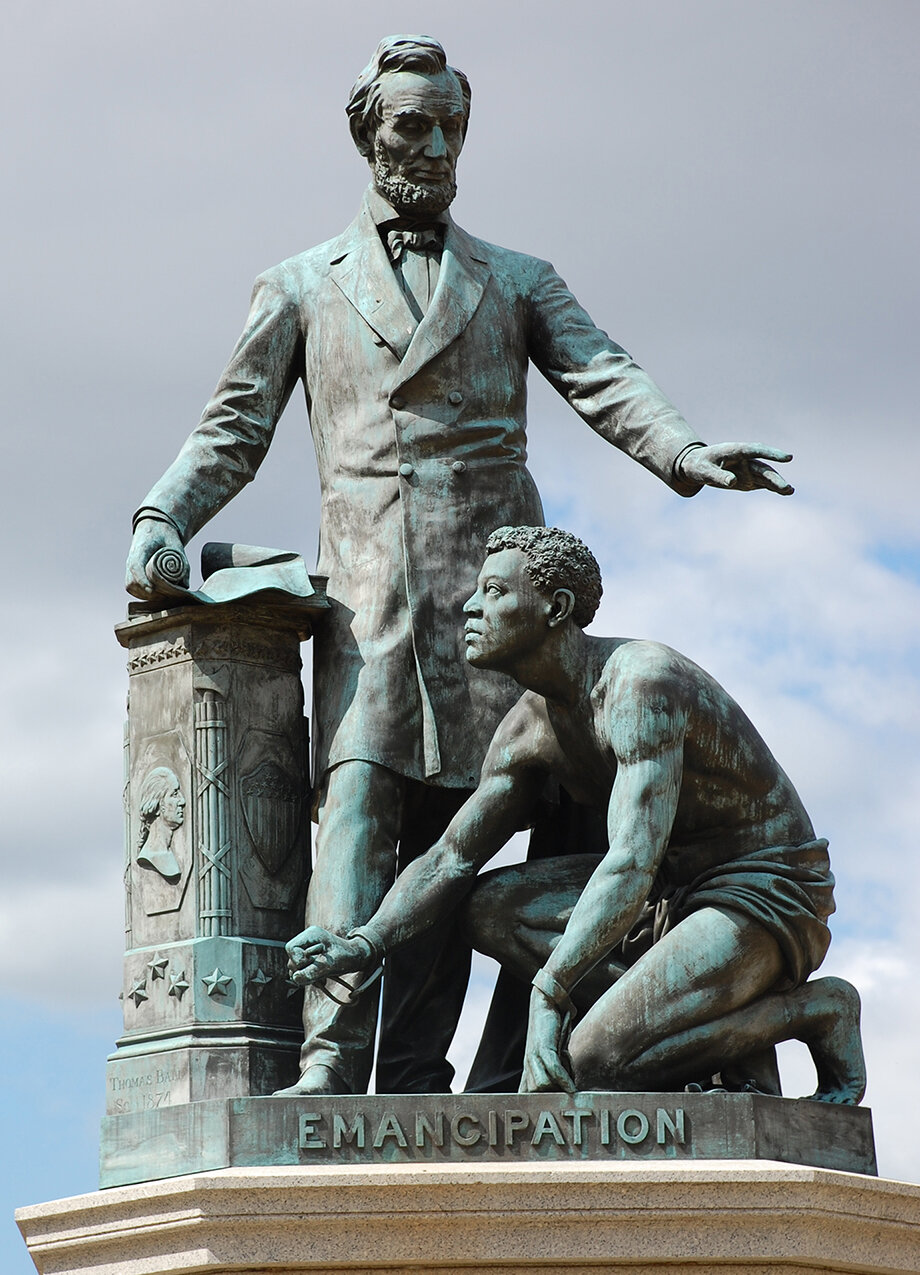

In December 2020, city officials in Boston removed from a public square a statue of Lincoln, commonly known as the Emancipation Group, in which a standing Lincoln appears to bestow freedom on a kneeling Black man. This was a copy of a Thomas Ball statue erected in 1876 that is still on site in Washington, D.C. The Boston statue had drawn the ire of residents who found its composition demeaning, seeing it as emphasizing Black subservience.

Boston officials remove a statue of Abraham Lincoln standing above a kneeling emancipated person on December 29, 2020. Thomas Ball, Emancipation Group (recasting of Freedmen’s Memorial), 1879, bronze, photo © Nancy Lane/MediaNews Group/Boston Herald

A reckoning

To some observers, the removal of statues of Abraham Lincoln—the sixteenth president of the United States, who led the nation to victory in the Civil War (1861–65) and signed the Emancipation Proclamation—was a sign that the recent iconoclasm of Civil War statues had gone too far. “What started out as an earnest effort by some to remove statues glorifying a rebellion by the slavery-defending Confederacy has devolved into an absurd effort to destroy all vestiges of the past,” opined the editorial board of the Denver Gazette, noting that the original Ball statue in Washington, D.C. had been financed by formerly enslaved Black people in the years after the Civil War. [1] Others celebrated the removal of statues which they had perceived as chilling public reminders of white supremacy and Indigenous erasure. The Boston mayor’s office told the press that “The decision for removal acknowledges the statue’s role in perpetuating harmful prejudices and obscuring the role of Black Americans in shaping the nation’s fight for freedom.” [2]

But the Portland and Boston Lincoln statues are only two of the more than 100 statues of Civil War-era public figures that have been removed since 2015, with most protesters and cities focusing their efforts on removing monuments honoring the defeated Confederacy. Although there was no small amount of controversy over taking down Confederate monuments, efforts to remove statues honoring figures from the victorious U.S. forces—like Lincoln—has led to some head scratching. Weren’t these the good guys in the Civil War, who kept the country from splitting apart and brought about emancipation? Why should their likenesses be torn down alongside those of the men who fought to preserve slavery? Are “all vestiges of the past” really doomed to be expunged from the landscape?

Mythmaking

The purpose of public monuments, and which voices and images ought to be celebrated in public art and memorials, is a topic that will likely continue to be hotly debated in the coming years. But the calls for removing monuments to Abraham Lincoln and other heroes of the United States during the Civil War help to illuminate the ways in which these portrayals have often escaped the scrutiny given to Confederate monuments.

When we think of the mythology that emerged from the American Civil War, we tend to focus on the myth of the Lost Cause—white southerners’ efforts to rewrite the reasons for the war and its outcome. But white northerners also engaged in mythmaking, elevating political and military leaders to sainthood and downplaying the importance of emancipation (and self-emancipation) in the war effort. [3] Therefore, monuments to U.S. Civil War heroes, just like monuments to the Confederacy, are not neutral or objective records of the past; like any work of art or historical source they promote some ideas and obscure others.

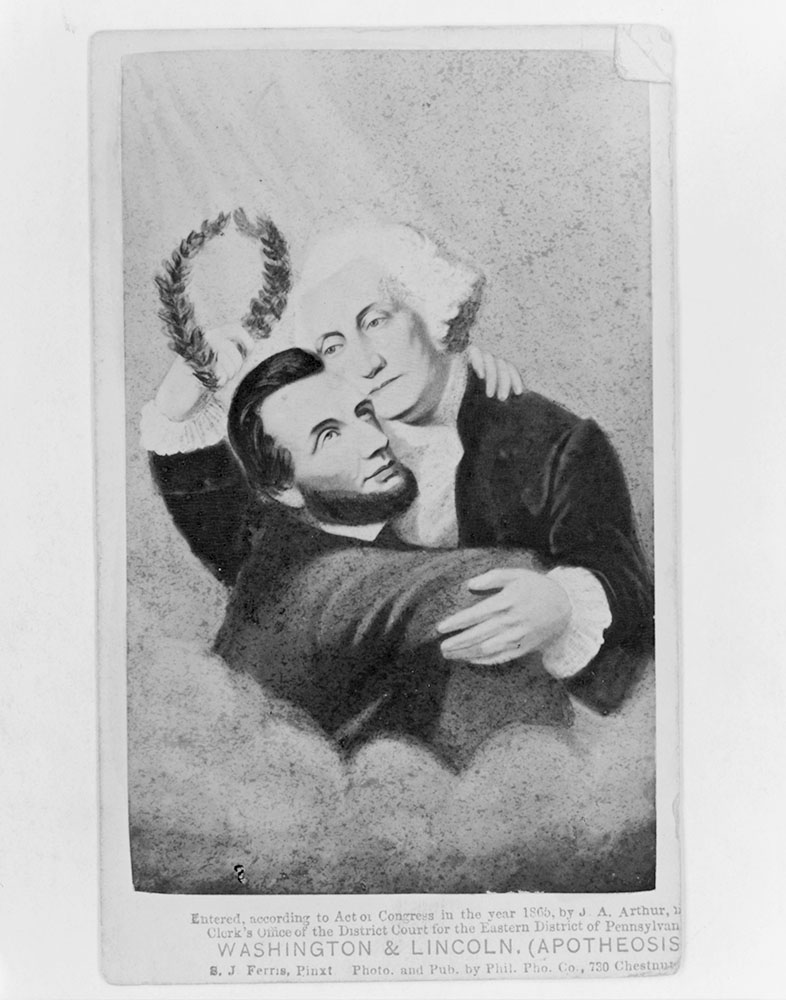

S.J. Ferris, Washington & Lincoln (Apotheosis), 1865, albumen print on carte-de-visite (Library of Congress)

This essay will examine visual depictions of Abraham Lincoln, whose image has mirrored the broader project of northern Civil War memory and mythmaking. While he was in office, Lincoln’s image was closely tied to public opinion of the war effort and the actions of his administration. But after his assassination—the first of a president in U.S. history—Lincoln was portrayed in art as a Christ-like figure who had died in pursuit of the Union’s salvation. Art celebrating the Emancipation Proclamation celebrated Lincoln alone, rather than a vast network of abolitionists, soldiers, and self-emancipated Black people who worked to end slavery. These images both reflected and helped to reinforce the process of reunion that took place between white northerners and former Confederates in the fifty years after the Civil War. As the federal government abandoned its pursuit of Black citizenship, memorials ceased to emphasize the end of slavery as an important part of U.S. victory in the Civil War.

Lincoln’s image during the Civil War

Depictions of Lincoln during his lifetime and during the war itself remind us that he was far from universally beloved: not only was Lincoln broadly despised by southern slaveholders who fomented secession after his election in 1860, Lincoln was also a focus of criticism by northerners. As a leader, he faced accusations of incompetence, of being both too radical and too conservative in his stance toward slavery, of being both too willing to sacrifice American lives in the pursuit of winning the Civil War and not willing enough. The only thing that his critics seemed to agree on was that he was an exceptionally ugly man, a fact that Lincoln himself made light of. “If I had two faces,” he joked in response to accusations of being deceitful, “would I be wearing this one?” [4]

During his more than four years in office, Lincoln and his supporters faced opposition from many groups in the North in addition to the South. There were Copperheads who sympathized with the slaveholding rebels and, on the other side, abolitionists who demanded immediate emancipation. The Civil War, a conflict northerners initially imagined would last mere months, stretched to four years and hundreds of thousands of casualties. As deaths mounted, contemporaries criticized Lincoln’s management of the war, and political cartoonists took aim at him.

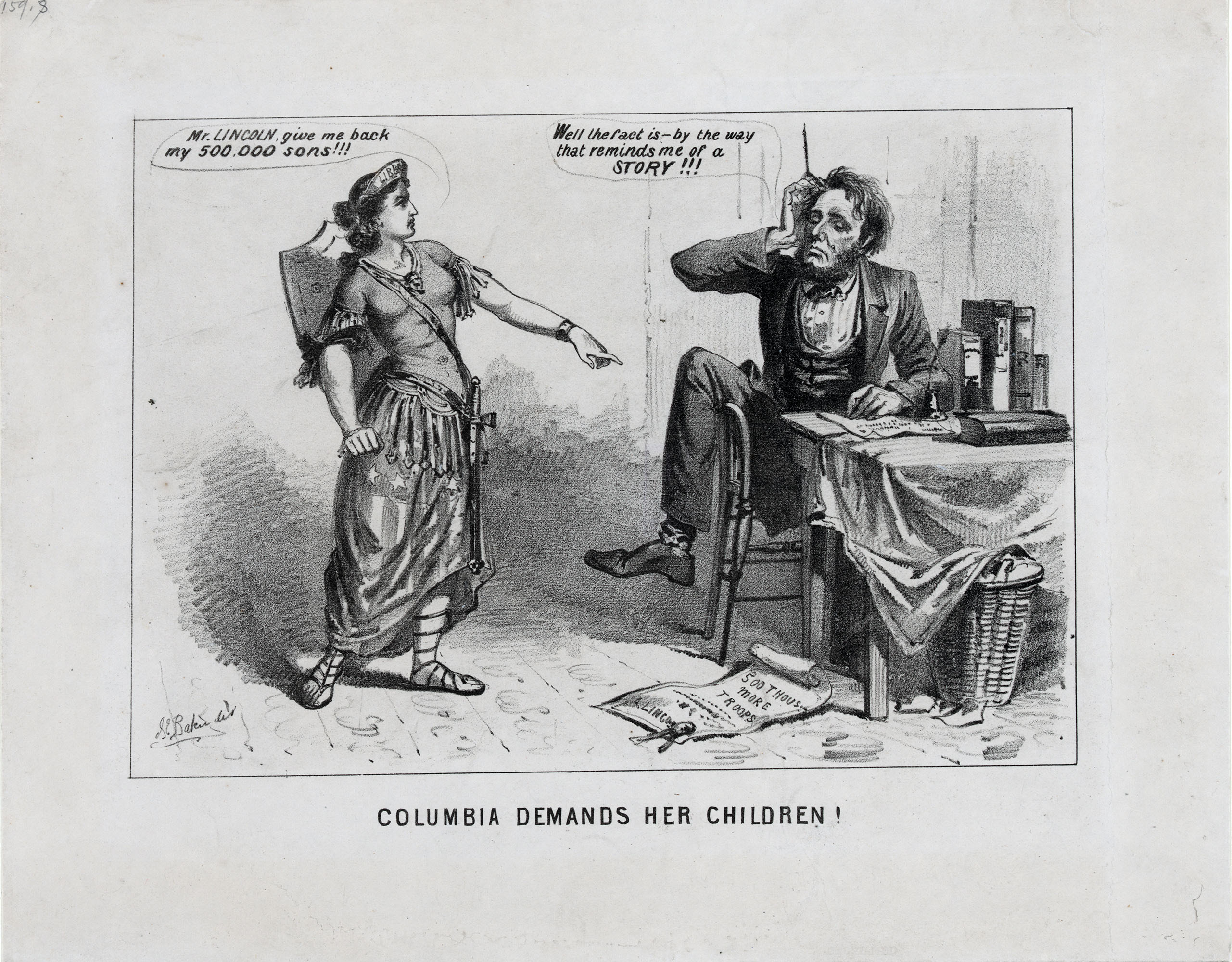

Political cartoon critiquing Lincoln’s handling of the war. Joseph E. Baker, Columbia Demands Her Children! Boston, 1864, lithograph (Library of Congress)

In this political cartoon from 1864, the figure of Columbia (an allegorical representation of the United States) wears ancient Roman garb, an American flag skirt, a shield on her back, and a crown inscribed “Liberty” as she accuses Lincoln of wasting the lives of U.S. soldiers. She points at Lincoln’s request for more troops, and demands, “Mr. Lincoln, give me back my 500,000 sons!” (the approximate number of men who had died in the war up until that point). Lincoln is portrayed as disheveled and grotesque, his leg thrown clumsily over a chair. A proclamation calling for more troops lies at his feet as he tries to distract Columbia by mumbling “Well the fact is—by the way that reminds me of a STORY!!!” The artist channeled the anger felt by many white northerners that their sacrifices had not translated into victory after three years of fighting, and that Lincoln had mismanaged the war. After Lincoln’s death in 1865, however, such unflattering depictions became extremely rare. This representation of Lincoln as incompetent contrasts with the god-like depictions made after his death, where he bestows liberty on enslaved people who appear unable to take action on their own behalf.

Apotheosis and idealization

In the years since his death, the instantly recognizable figure of Lincoln has become a symbol of emancipation, freedom, honesty, and civic virtue. Why and how did this transformation occur? First, Lincoln was assassinated, not only in the midst of the triumph of U.S. forces at the end of the Civil War but also on Good Friday, the day that Christians commemorate the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. He became not just a president but a martyr, ascending to a national pantheon along with George Washington.

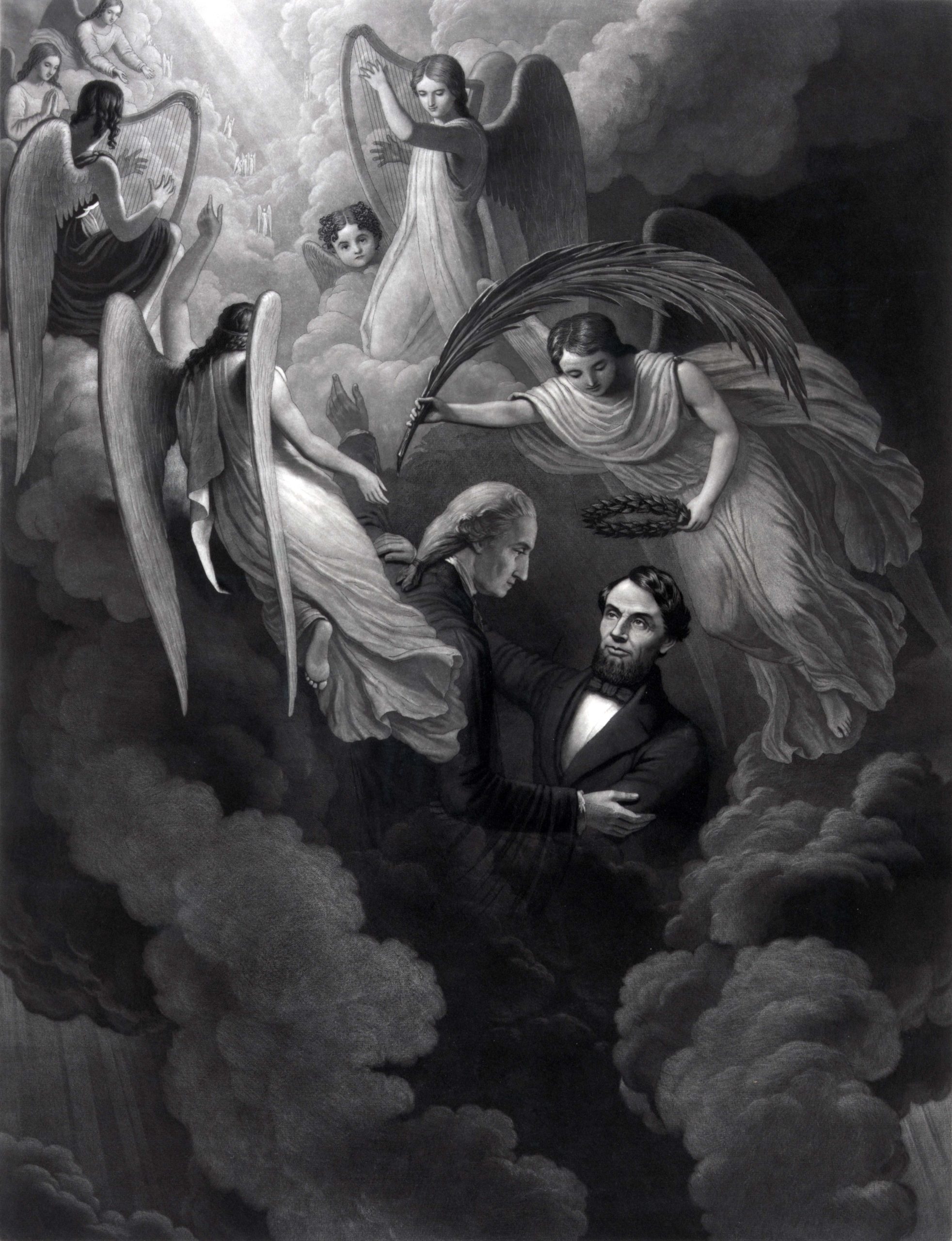

John Sartain, after a design by W.H. Hermans, Abraham Lincoln, the Martyr, Victorious, 1866, engraving, 61 x 48 cm (Library of Congress)

Lincoln was the first U.S. president to be assassinated, and Americans reacted to his death with shock. Soon after, an explosion of images of Lincoln appeared that mourned his death and depicted him as a martyr. Several illustrators imagined what happened to Lincoln’s spirit after he died, showing his apotheosis (transformation into a divine figure), such as John Sartain’s Abraham Lincoln, the Martyr, Victorious. In a long tradition of deification of leaders going back to ancient images of Roman emperors, Lincoln’s spirit ascends to heaven, where he is welcomed by George Washington and angels, some playing harps. One angel crowns him with laurels and holds a palm frond—both Roman symbols of victory (the palm was also a Christian symbol of eternal life and often depicted in images of martyred saints. The palm frond would also have reminded contemporary viewers of Jesus Christ, who was welcomed into Jerusalem with palms.

But the idealizing imagery of Lincoln in the wake of his assassination and the victory of the United States in the Civil War increasingly marginalized the most important participants in the saga of emancipation: the formerly enslaved people themselves. It also obscured Lincoln’s interactions with Indigenous people, whose suffering increased as a result of U.S. Army actions in the Civil War. Although Lincoln’s policies toward Indigenous peoples were not markedly different from those of earlier administrations, the Civil War’s impact on native communities was catastrophic. U.S. Army units forced thousands of Diné (Navajo) and Apaches in the southwest to march to a concentration camp in Bosque Redondo, New Mexico, where they were interned in conditions so unsanitary that more than a quarter of them died. The Third Colorado Cavalry attacked a settlement of Cheyenne and Arapaho women, children, and elderly people and murdered at least 150 of them in a rampage known as the Sand Creek massacre. Until recently, neither of these grim episodes has figured much in public histories of the Civil War.

Envisioning emancipation

In September 1862, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that all enslaved people living in areas then in rebellion against the United States would become forever free on January 1, 1863. Artists hoping to commemorate this world-changing event faced a unique challenge: how could they depict emancipation? The Black people who were enslaved at 11:59 pm on December 31, 1862 would look exactly the same at 12:00am on January 1, 1863 when they became legally free. Was emancipation a process of subtraction—taking away chains, perhaps—or was it the addition of something new?

Abraham Lincoln may have signed the Emancipation Proclamation, but it was enslaved people themselves who made emancipation a reality, forcing the issue long before Lincoln accepted emancipation as a war goal. Many escaped at great personal risk, often making their way to U.S Army lines and serving in the war. In addition to providing military intelligence, many of these refugees went on to enlist to fight their former enslavers directly. One person wrote the Emancipation Proclamation, while millions more enacted it—often at great cost to themselves and their families.

P.S. Duval & Son after a drawing by R. Morris Swander, Emancipation Proclamations, Allegorical Portrait of Abraham Lincoln, Philadelphia: Swander Bishop & Co., 1865, engraving, 77.4 x 62.4 cm (Brown University Library)

Visual representations of emancipation, however, focused on Lincoln’s role as author of the Proclamation, sidelining or erasing the role of Black people altogether. An 1865 engraving depicts Lincoln made of the words of the Emancipation Proclamation, with the portrait separating two vignettes below: one showing an enslaved man being lashed, another showing him being armed with a sword by Columbia (an allegorical representation of the United States) and sent off into battle with another Black man in an army uniform. Early images of emancipation, like these vignettes in the Emancipation Proclamations allegory, often portrayed formerly enslaved men joining the military and achieving full citizenship.

Dennis Malone Carter, Lincoln’s Drive Through Richmond, 1866, oil on canvas, 45 x 68 inches (Chicago History Museum)

But others saw Lincoln as the divine deliverer, like Dennis Malone Carter’s 1866 painting Lincoln’s Drive Through Richmond. Here, the artist portrays Lincoln’s April 4, 1865 visit to the recently captured Confederate capital of Richmond, where he was greeted by grateful Black and white citizens. Sunlight falling on the wall behind Lincoln’s head gives the effect of a halo.

Not all attempts to commemorate emancipation in art focused on Lincoln alone. When formerly enslaved people began collecting money after Lincoln’s death to build a monument in his honor, some designs foregrounded the Black struggle for emancipation and equal citizenship.

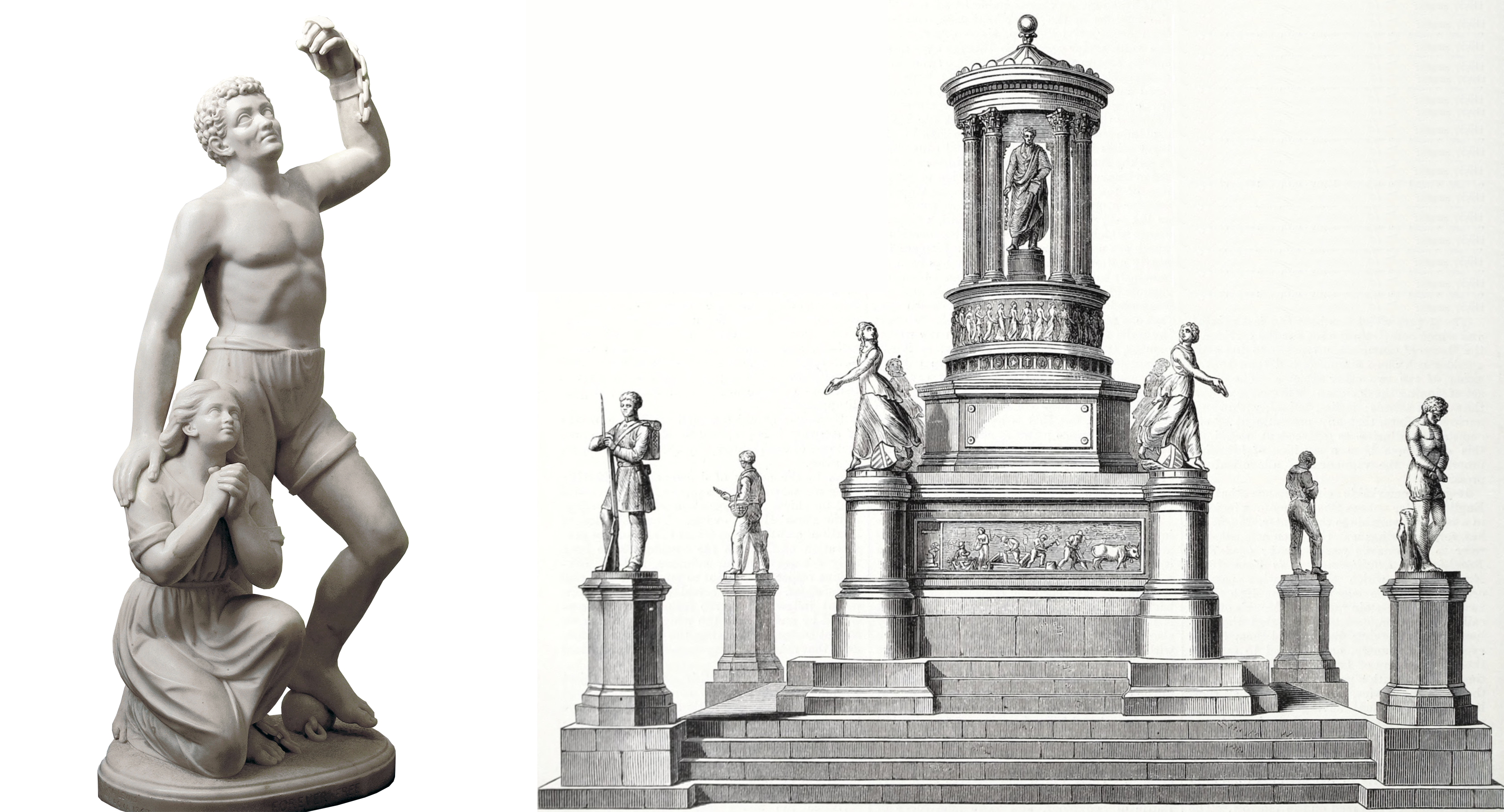

Left: Edmonia Lewis, Forever Free, 1867, marble, 106 cm high (Howard University Gallery of Art; photo: Art History Project); Right: Harriet Hosmer, early design for Freedmen’s Memorial to Lincoln, published in The Art-Journal, (January 1, 1868), London: Virtue & Co., p. 8.

Neoclassical sculptor Edmonia Lewis, an American sculptor who had both Black and Indigenous ancestry who worked in Rome, created an emancipation group called Forever Free soon after the conclusion of the Civil War. Lewis’s sculpture centers on the experience of a Black man and woman at the moment of emancipation. Overcoming the common visual trope of the kneeling slave begging for freedom seen in much abolitionist imagery, Lewis depicts a formerly enslaved man raising one arm with a broken shackle in a victorious attitude, his other hand resting on the shoulder of a kneeling woman whose own hands are clasped in prayer as if thanking God for the gift of freedom. With a protective, independent male figure and chaste, pious female figure, Lewis suggested that this newly free Black couple is finally able to participate in the family framework that was prized in the Victorian era. [5] Another proposed sculpture group, white female sculptor Harriet Hosmer’s unrealized designs for an emancipation memorial, featured a sculptural cycle of Black history with four standing male figures at each corner, representing kidnapping, enslavement, self-emancipation, and military service. [6] The figures are shown standing and appear as dignified and active agents in their own destinies.

Thomas Ball, Emancipation Memorial, 1876, bronze, Lincoln Park, Washington, D.C. (photo: Renée Ater)

Eliminating Black agency

But Hosmer’s design was ultimately discarded by the committee tasked with choosing the form of the monument. Despite being funded by the formerly enslaved, the committee sought no direction from their Black patrons, and ultimately chose to build a smaller group sculpted by American sculptor Thomas Ball. The Ball memorial group, which was erected in Lincoln Park in Washington, D.C. (and whose copy was removed from view in Boston, as discussed earlier), showed Lincoln holding the Emancipation Proclamation and bestowing freedom on a semi-nude Black man crouched at his feet. Unlike Hosmer’s active, standing men, the Ball statue’s enslaved man is passive and diminished.

The statue implies that freedom was a gift given by Lincoln to the grateful enslaved. This is problematic in several ways: first, it eliminates the agency of Black people in obtaining their own freedom; second, it presents emancipation as a single event rather than an ongoing process of securing equality and citizenship; and third, it freezes the Black man in a powerless pose, forever locked in a state of subservience—while suggesting that he ought to be grateful for it.

This change in narratives—from Hosmer’s design foregrounding Black citizenship to Ball’s forever-kneeling passive recipient of freedom—tracked with the larger social changes in the period we call Reconstruction. By the time the monument was erected in 1876, the federal government and the Republican Party had abandoned their commitment to Black equality and allowed white supremacist state governments to retake power in the South. Frederick Douglass, who gave a speech at the Ball statue’s dedication in Washington, D.C., in 1876, reportedly disliked the pose of the kneeling figure, which did not impart a “manly attitude” indicative of freedom. [7] Douglass’s remarks laid bare the tenuous relationship between Black freedom and Abraham Lincoln, stating simply that Lincoln “was pre-eminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men . . . [but] we came to the conclusion that the hour and the man of our redemption had somehow met in the person of Abraham Lincoln.” [8]

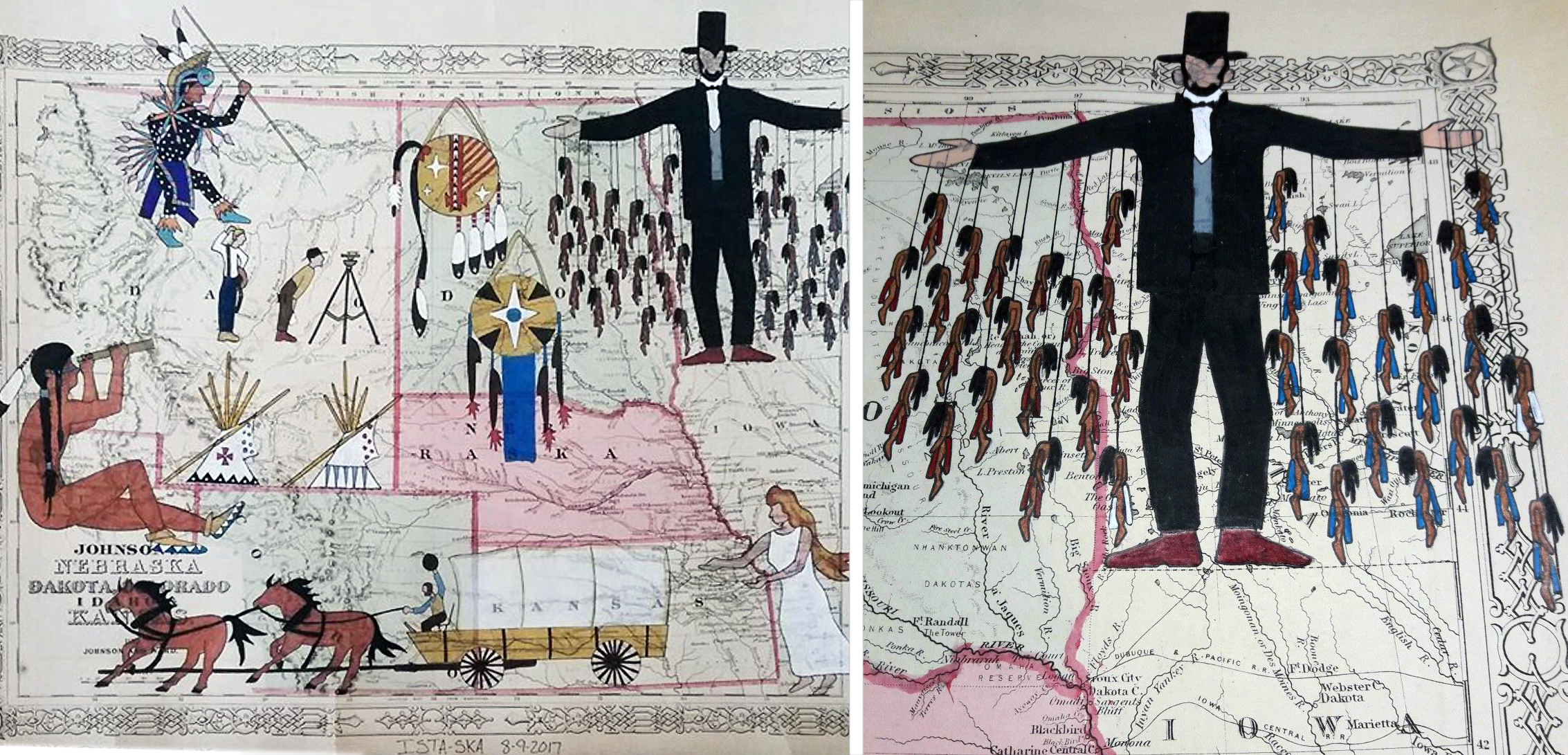

Travis Blackbird, Ledger art on map, (and detail at right), 2017, ink on antique ledger, © Travis Blackbird used by permission

Lincoln’s image and Indigenous genocide

Although many artists have depicted Lincoln as a Christ-like figure, a work of contemporary ledger art by Travis Blackbird (Omaha/Oglala Lakota) includes an image of Lincoln on a map of western states, atop the state of Minnesota. Lincoln’s stance, with his arms outstretched, ironically mimics Christ on the cross or the Virgin Misericordia, who protects the blessed beneath her cloak. In 1862, Dakotas were starving in Minnesota after white settlers pushed them off their lands and the U.S. government failed to provide the food and money it had promised in earlier treaties. A faction of Dakota men attacked the reservation administration building where unscrupulous government agents had broken the terms of the treaty by refusing to sell them food, and the uprising escalated into all-out warfare. Throughout August and September of that year, Minnesota infantry regiments recruited for the U.S. Army turned their sights on the Dakota forces. After they were defeated at the Battle of Wood Lake in late September, the Dakotas were subjected to military trials that resulted in sentencing more than 300 men to death. Abraham Lincoln commuted the sentences of most but signed an order to execute 38 Dakota men, which was the largest mass execution in U.S. history. [9]

Blackbird wrestles with this legacy by showing 38 hanged Dakota men dangling from Lincoln’s arms: Lincoln’s quasi-religious status has condemned, rather than saved these men. Blackbird positions Lincoln among other symbols of white incursion into Indigenous land, with surveyors and a covered wagon suggesting the influx of white settlers after Lincoln signed the Homestead Act in 1862. At the bottom right, a figure of Columbia drawn from John Gast’s painting American Progress symbolizes Manifest Destiny, the imperialist idea that white Americans were destined to occupy North America from Atlantic to Pacific, which spurred westward expansion and Indigenous genocide.

The Civil War was caused, in part, by westward expansion—or, more precisely, by the conflict over the future of slavery in the West. But neither white northerners or southerners envisioned a place for Indigenous people in the lands they intended to possess. For decades, U.S. history books taught the Civil War and westward expansion after the war as separate units, subtly signaling that the two topics are unrelated. But in the last decade, scholars have emphasized the connections between the war (that was largely fought in the South) and the conflict between Indigenous people and white settlers in the West. [10]

Mathew Brady, Delegation of Plains peoples to the White House, 1863, photograph (White House)

Lincoln’s policy proposals were based around reserving the West for individual white farmers to counteract the influence of slaveholders. In office, he signed The Homestead Act and the Pacific Railway Act, both signature policies of Lincoln’s administration. These acts gave Indigenous lands to white settlers and railroad companies and pushed Plains peoples onto reservations. Although Lincoln invited a delegation of Plains peoples to the White House in 1863—whom he urged not to ally with Confederates, and who in turn urged him to honor land treaties—he continued ongoing U.S. government efforts to force Indigenous people onto reservations. There was no equivalent to the Emancipation Proclamation for Indigenous peoples.

Lincoln’s legacy

Although there is much to celebrate in Lincoln’s legacy, there’s also much to critique. Looking beyond an idealized image of Lincoln helps us to see the past more clearly and to confront the legacy of the Civil War in all its complexity: a war of freedom, but one with catastrophic effects on Indigenous people. How the actions of U.S. forces have been remembered must also be viewed anew: just as white southerners championed a highly subjective and damaging narrative of the war’s causes and consequences, white northerners’ story of victory and emancipation has left out the contributions of Black Americans and erased Indigenous suffering at the hands of the army.