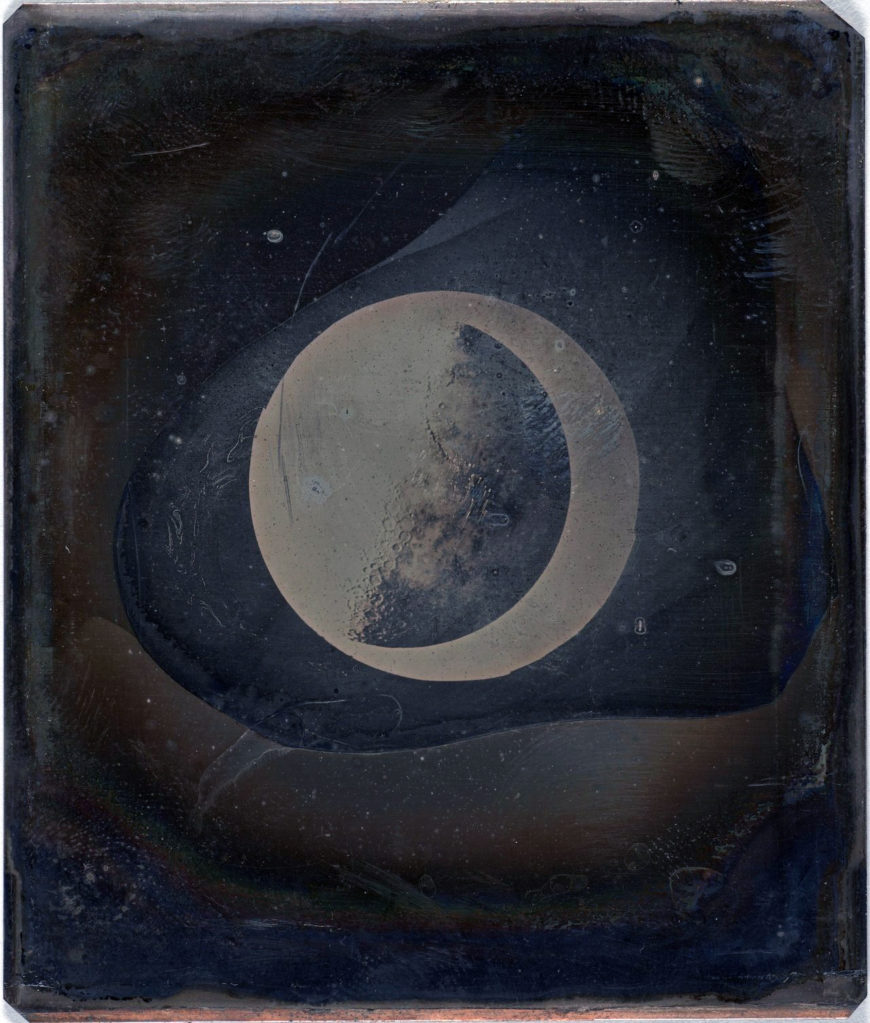

John Whipple, William Bond, and George Bond, The Moon, No. 37, 1851, daguerreotype made through Great Refractor Equatorial Mount Telescope, Harvard College Observatory, case size 4-½ x 3-¼ inches

Tilting the mirrored daguerreotype’s surface reveals a 2 ½-inch-diameter-wide image of The Moon, laterally reversed (a distortion of the daguerreotype process), and with a scattering of pitted craters and darker-gray smooth areas. As the Moon falls into darkness, the craters produce dramatic dark shadows. The unprecedented amount of detail offered by lunar photographs such as this one was celebrated in scientific and artistic societies.

The Moon daguerreotypes—made collaboratively by photographer John Adams Whipple and the father-son duo of American astronomers William and George Bond—were hailed at the Great Exhibition of 1851 as

one of the most satisfactory attempts that has yet been made to realise, by a photographic process, the telescopic appearance of a heavenly body, and must be regarded as indicating the commencement of a new era in astronomical representation. The Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue to the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations (London: Spicer Brothers 1852) [1]

The Moon daguerreotypes were said to be “of such excellence” at that Exposition that they created an excited “veritable furor,” won a Gold Medal, and further established the reputations of American astronomers William and George Bond. [2]

John Adams Whipple, a Boston-based commercial photographer who kept up his studio practice while also being the U.S.’s first manufacturer of daguerreotype chemistry, was recognized for his aesthetic, technical, and scientific accomplishments by two European cultural societies of high esteem: the Royal Society of Arts and Manufactures in London, and the French Academy of Science in Paris.

John Whipple, William Bond, and George Bond, The Moon, February 26, 1852, daguerreotype made through Great Refractor Equatorial Mount Telescope, Harvard College Observatory

Achieving clear and celebrated daguerreotypes from the unprecedented process of photographing through a telescope (at Harvard University) was anything but easy. Whipple and the Bonds met a steady stream of setbacks and accidents. They over- and under-exposed images, needed to equip their telescope with additional gadgetry, and occasionally were irritable with each other. During an early experiment, William Bond’s coat sleeve was set on fire by a beam of sunlight that was magnified by a telescopic lens. [3] William Bond fretted and quibbled with Whipple over the necessity of attaching a camera to his new telescope, and the elder Bond lamented the attention and time with the Great Refractor that Whipple’s photography commanded. [4] In addition, the telescope was so large (more than 22 feet long) that it moved slightly as photographs were exposed. The team created a timing device that allowed the telescope to accurately track the Moon and reduce the blur its movement and the Earth’s rotation caused on the photographic plate.

The daguerreotype process also had drawbacks. The process had only been introduced a couple of decades earlier, and had never been used to record light seen through telescopes, in nighttime conditions, with a severely limited light source. As one-of-a-kind images, daguerreotypes could only be reproduced by re-photographing them. That made them difficult to share. And the daguerreotype plates also needed to be small to focus sufficient light to capture an image of the Moon. [5]

Any one of these challenges would have deterred most practitioners from pursuing astronomical photography. In fact, as Alan W. Hirshfeld points out: “Despite these early successes, most professional astronomers shunned the photographic process. Photography, as it was practiced then, was noxious, imprecise, and inefficient. Few astronomers envisioned the new technology’s potential to surpass the capabilities of human sight at the eyepiece of the telescope.” [6]

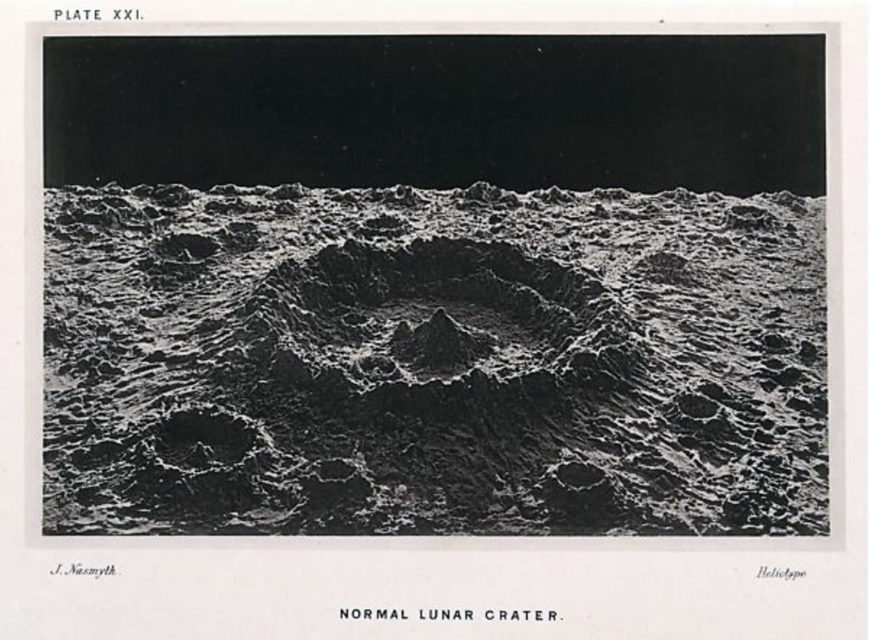

Plaster model of the Moon. James Nasmyth, Normal Lunar Crater, in The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite, 1874, heliotype, 28.5 x 23 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Nevertheless, the Bonds and Whipple—exceptions to this inclination to avoid the medium—collaborated on astronomical photography for a total of six years, made about 70 daguerreotypes, and were widely regarded as this genre’s first successful practitioners. Their meticulously-detailed daguerreotypes helped prove photography’s value to astronomy, as they replaced the previous practices of drawing Moon views and making plaster models for further scientific study. The Whipple-Bond daguerreotypes would pre-date the first photographs of the satellite’s surface by spacecraft (1964), and by a human on the Moon (1969), by almost 120 years.

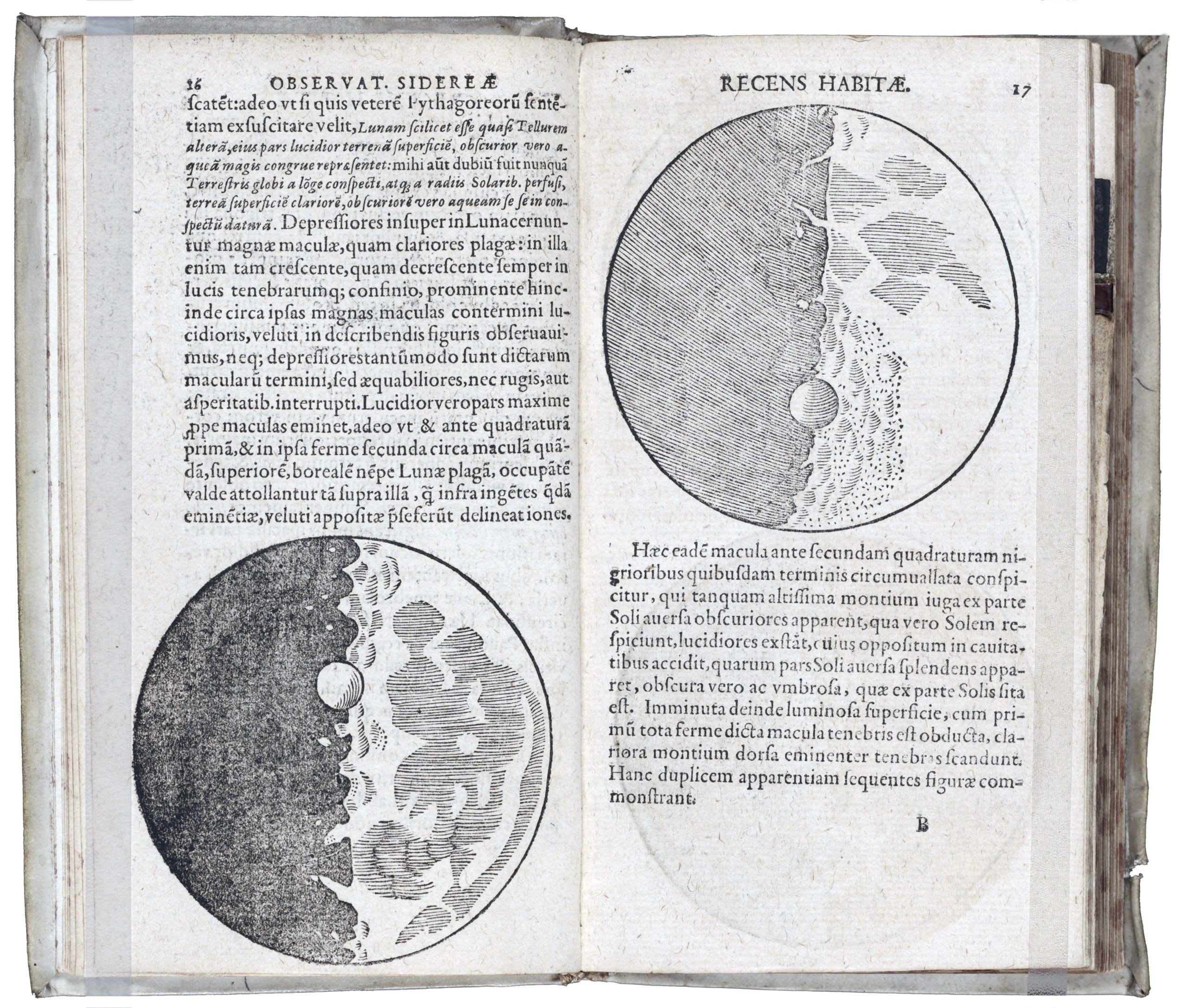

Galileo Galilei, Sidereus nuncius (in Paltheniano: Prostat Francof, 1610), pages 18–19 (Yale University Library)

A fervor for astronomy

How did this fruitful collaboration come to be? After Halley’s Comet traversed the skies in 1835, followed by The Great Comet in 1843, the public’s fervor for astronomy reached a new peak. Boston’s upper class donated the funding for building an observatory at Harvard College, and to procure a state-of-the-art, research-quality telescope for it. After all, as U.S. President (and Harvard alumni) John Quincy Adams told Congress in 1825, “Europe had more than 130 observatories, while the United States had none.” [7]

To make this photograph, Whipple exposed the light-sensitive plate to the light emanating from the star for 90 seconds. George Bond and John Whipple, Vega (Alpha Lyrae), July 16-17, 1850, daguerreotype

In 1847, the new Harvard Observatory installed a 15-inch, German-made, Great Refractor equatorial mount telescope, then the largest in the world. Starting a few months later, William Cranch Bond, former clock-maker-turned-Director of the Harvard Observatory, invited established commercial photographer Whipple to make daguerreotypes of the Sun and Moon using the new telescope, the proud centerpiece of the new observatory, in collaboration with him and his son, George. Together, Whipple and the Bonds formed a productive partnership that founded the sub-field of celestial photography. They worked for about six years to produce photographs of various celestial phenomena, including the star Vega (Alpha Lyrae, 1850), The Moon, No. 37, 1851 (above), and Jupiter (1851), among others. With these images, William Bond hoped to bolster public support for the observatory by highlighting research of “broad appeal and interest.” [8]

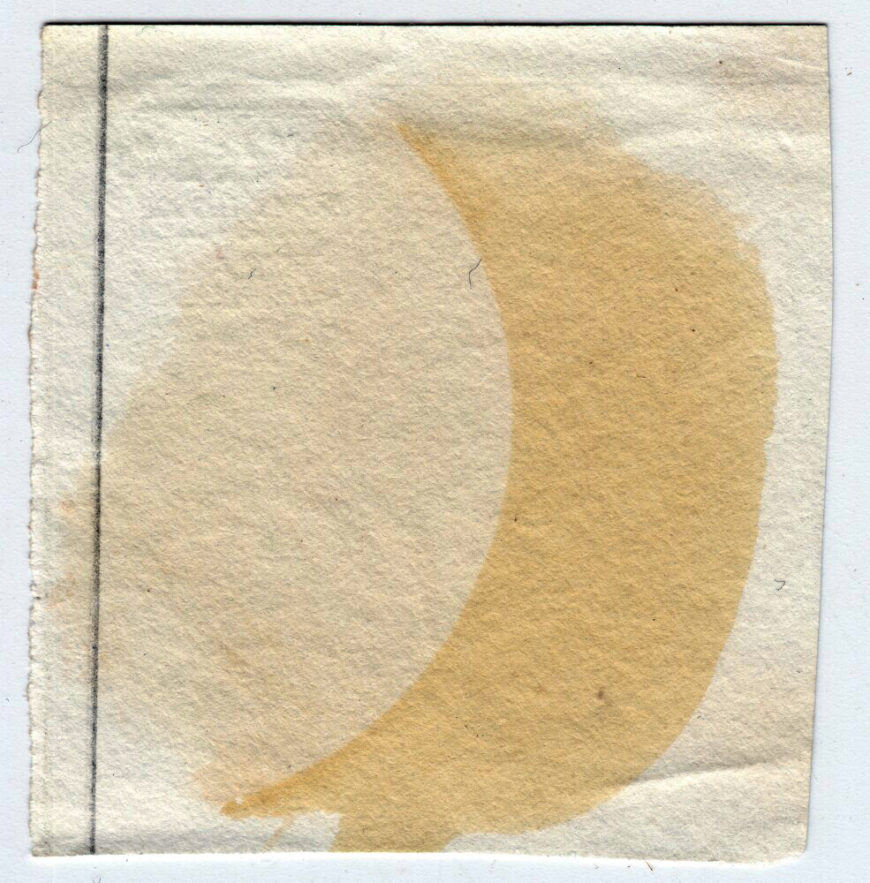

William Henry Fox Talbot, Possibly Disk of the Sun or Moon in Telescope – Experimental Image, n.d. (Bodleian Library)

Earlier attempts to photograph the Moon

Although the Whipple-Bond daguerreotypes were not the first ones made of the Moon, they were the least blurry, the most detailed, and the largest ones that survived. Louis-Jacques Mandé Daguerre claimed to had taken the first lunar daguerreotype on January 2, 1839, just five days before his invention of the medium of photography would be announced to the public. His studio and his archive were destroyed by a fire two months later, destroying the images. British pioneering photographer William Henry Fox Talbot produced several undated experimental images that resemble the Moon or Sun using his paper-based calotype process, but the images are too faint, perhaps, to make certain identification of the subject possible.

However, New York University chemistry professor John William Draper’s Moon from 1840—previously assumed to have been destroyed in a fire at the New York Lyceum in 1866—reveals the Moon about one inch wide, surrounded by a white circle and an irregularly shaped black background sky. Draper’s image, which resulted from an exposure of about 20 minutes, likely was made in the daytime, and aligned to appear on a circular uncovered part of the plate with the background masked off. This would have allowed Draper to maximize the amount of light available to illuminate the Moon’s surface, although it also added a white semi-circle around the right side of the Moon’s image. The expected night-time sky was added in a separate exposure. Although it was not the result of a single, full-frame exposure, Draper’s Moon offered unprecedented detail of the satellite’s surface details, even if his work was overshadowed by the later, larger Moon daguerreotypes of Whipple and the Bonds. [9] However, Draper’s experiments followed the official announcement of the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839 by only one year, immediately suggesting the early recognition of photography’s promise as a medium for recording scientific phenomena.