Jorge González Camarena, Presencia de América Latina, 1964–65, acrylic, 35.2 x 6 m (Universidad de Concepción, Chile; photo: Farisori, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Why is it important to study Latin American art today?

Richard Evans, Portrait of Henry Christophe, King of Haiti, c. 1816, oil on canvas, 34¼” x 25½” (University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus)

The study of Latin America and Latin American art is more relevant today than ever. In the United States, the burgeoning population of Latinos—people of Latin American descent—and consequently the rise of Spanish (and Spanglish) speakers, Latino musical genres, literature, and visual arts, require that we better understand the cultural origins of these diverse communities. Even beyond our borders, Latin American countries continue to exert influence over political and economic policies, while their artistic traditions are every day made more and more accessible at cultural institutions like art museums, which regularly exhibit the work of Latin American artists. In many ways, Latin American and Latino culture is an inescapable reality; thus, it is up to us, for the benefits of appreciation and integration, to tackle the difficult question of what it means to be from Latin America.

For many of us, Latin America is not an entirely foreign concept—in fact, our knowledge of it is most likely defined by a particular country, food, music, or artist, and sadly, it is also sometimes clouded by cultural stereotypes. What many of us often overlook is the diversity of what it means to be Latin American and Latino. Interestingly, Latin America is not as different from the United States as we tend to think, since we both share in the history of conquest and imperialism, albeit from different perspectives. Thus the study of Latin American art should not necessarily be thought of as a narrative that is entirely separate from that of the United States, but rather as one that is shared.

Félix Parra, Episodes of the Conquest: Massacre of Cholula, 1877, oil on canvas, 65 x 106 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte (INBA), Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What do we mean by Latin America?

Latin America broadly refers to the countries in the Americas (including the Caribbean) whose national language is derived from Latin. These include countries where the languages of Spanish, Portuguese, and French are spoken. Latin America is therefore a historical term rooted in the colonial era, when these languages were introduced to the area by their respective European colonizers. The term itself, however, was not coined until the nineteenth century, when Argentinean jurist Carlos Calvo and French engineer Michel Chevalier, in reference to the Napoleonic invasion of Mexico in 1862, used the term “Latin” to denote difference from the “Anglo-Saxon” people of North America. It gained currency during the twentieth century when Mesoamerican, Central American, Caribbean, and South American countries sought to culturally distance themselves from North America, and more specifically, from the United States.

Today, Latin America is considered by many scholars to be an imprecise and highly problematic term, since it prescribes a collective entity to a conglomerate of countries that remain vastly different. In the case of countries that share the same language, their cultural bond is much stronger, since, despite their potentially different pre-conquest origins, they continue to share collective colonial histories and contemporary postcolonial predicaments. Spanish-speaking countries are therefore known as Spanish America or Hispanoamérica, while those that were colonized by the Iberian countries of Spain and Portugal fall under the broader category of Iberoamérica, thus including Brazil. In addition to these Latin-derived languages, Indigenous tongues like Quechua, spoken by more than 8 million people in South America, are still preserved today. When discussing countries such as French-speaking Haiti and Spanish-speaking Mexico, the similarities become much harder to articulate.

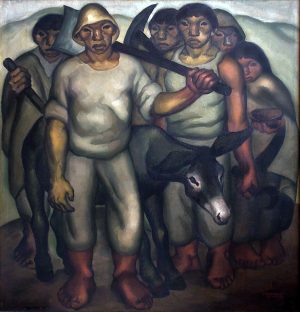

Oswaldo Guayasamín, The Workers, oil on canvas, 1942, oil on canvas, 170 x 170 cm (Fundación Guayasamín, Quito, Ecuador)

That said, the collective experiences of the conquest, slavery, and imperialism—and even today, those of underdevelopment, environmental degradation, poverty, and inequality—prove to be an undeniable unifying force, and as the artworks of these countries demonstrate, the idea of both a collective and local experience exists among the selected countries. For the purposes of clarity, the term Latin America is used loosely, whether referring to the pre- or post-conquest era. At the same time, however, this term will be challenged in order to demonstrate both the limitations and benefits of thinking of Latin American art as a shared artistic tradition.

It is anachronistic to discuss a Latin American artistic tradition before independence, and as a result, pre-Columbian and colonial art are discussed according to specific regions. However, it is best to approach the art of the 19th and 20th centuries as a whole, in large part due to the emergence of Latin Americanism and Pan-Americanism (a twentieth-century movement that rallied all American countries around a shared political, economic, and social agenda). Contemporary artists working in a globalized art world and often times outside of their country of origin give new meaning to what it means to not necessarily be a Latin American artist but rather a global one.

Geography

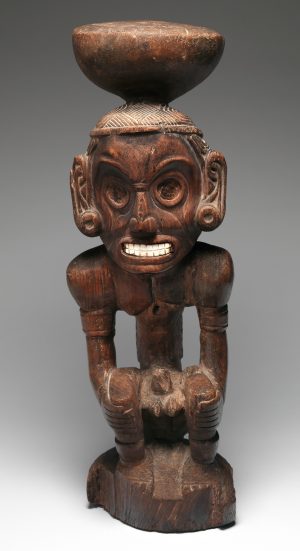

Deity Figure (Zemi), c. 1000, Dominican Republic, wood, shell, 68.5 x 21.9 x 23.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

While the countries of Latin America can be categorized by language, they can also be organized by region. Before 1492 C.E., the regions of Mesoamerica, the Isthmus (or Intermediate) Area, the Caribbean, and the Andes shared certain cultural traits, such as the same calendars, languages, and sports, as well as comparable artistic and architectural traditions. After colonization, however, the borders shifted somewhat with the creation of the viceroyalties of New Spain, Peru, New Granada, Río de la Plata, and Brazil. After independence (and still today), the countries stretching from Mexico to Honduras form part of the region of Mesoamerica (also known as Middle America since the Greek word “meso” means “middle”). Parts of Honduras and El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama, which lie to the south of Middle America, make up Central America, while all the countries to the south of Panama form part of South America. The Caribbean is sometimes considered part of Central America or, at times, entirely excluded. The United States also factors into this discussion of Latin American art—through the work of Latino, Chicano, and Nuyorican artists.

Lastly, it is important to note that when discussing specific Latin American countries, the geographical scope in question will correspond to the current, rather than former borders. While these linguistic and geographical parameters lend clarity to the study of Latin American art, they often obscure cultural differences that are not border-specific. The coastal cultures of Colombia and Venezuela, for instance, are closer to those of the Caribbean than to their mainland counterparts. This is reflected not only in the similar climate, diet, and customs of these particular areas, but also in their artistic production. The islands of the Caribbean, however, are also a geographical region (delineated by the Caribbean Sea), thus the distinction between regions depends on how and where you draw the borders—reminding us of the flexibility and variety of labels that can be employed to describe the same region.

Gold metallurgy originated in South America before spreading northward toward Panama and Costa Rica around 500 C.E., and arriving in Mesoamerica in 900 C.E. Diquís artist, Bat-Nosed Figure Pendant, 13th–16th century, gold, Costa Rica (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A similar distinction occurs in South America, where cultures vary greatly not necessarily across countries, but rather according to geographical landmarks, the two most prominent of which are the Andes Mountains and the Amazon Rainforest. Stretching from Chile to Venezuela, the Andes traverse the western portion of South America. At impressive heights and in snow-covered peaks, the Andean cultures of South America share irrigation techniques, textile traditions, and native languages, such as Quechua, that continue to this day. The Amazon, the world’s largest tropical rainforest, is contained mostly in Brazil, although it stretches into the bordering countries of Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana. Just these two landmarks, without mentioning the Pacific and Atlantic coastal cultures of South America, reveal the geographical, and thus cultural diversity of the area. Latin America is a useful, but by no means perfect term to describe a vast expanse of land that is historically, culturally, and geographically diverse.

From networks of exchange to a global trade network

From as early as the pre-Columbian era, there existed networks of exchange among the early civilizations of Latin America, through trade networks that stretched from Mesoamerica to South America. Limited by technology and transportation, forms of Indigenous contact were mainly restricted to the American continent. With the arrival of European conquistadores (Spanish for “conquerors”), the panorama changed entirely. Starting in the sixteenth century, and now exposed to Africa, through the transatlantic slave trade, and Asia, through the trade network of the Manila Galleon, Latin America entered into an era of global contact that continues to this day.

The Manila Galleon trade brought Japanese screens to Mexico, inspiring locally made objects like this. Folding Screen (biombo) with the Siege of Belgrade (visible) and Hunting Scene (reverse), c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Oscar Niemeyer, National Congress, 1956–60, Brasília, Brazil (photo: Mario Roberto Duran Ortiz, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

With the nineteenth-century struggles for independence, collaborations across countries increased, not to mention alliances were formed, that, although unsuccessful, nevertheless tried to articulate the idea of a collective Latin American entity. During the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, namely as a result of socio-political transformations, migration, exile, and diaspora (the dispersion of people from their homeland), travel became a trademark of modern art, further contributing to the internationalism of Latin American art. As a result of these networks of exchange, which began before colonization and continue to this day, Latin American art is difficult to categorize. It is, in fact, hybrid and pluralistic, the product of multi-cultural conditions.

“Non-Western” art?

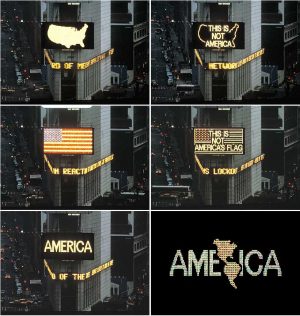

Alfredo Jaar, A Logo for America, as installed in 1987 (reprised 2014) Digital animation commissioned by The Public Art Fund, Times Square, New York, April 1987 (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift of the artist on the occasion of the Guggenheim UBS MAP Global Art Initiative, 2014) © Alfredo Jaar

It is critical to also consider the negative impact of the artificial insertion of Latin American art into Western and non-Western narratives. While the term “Western art” refers largely to Europe and North America, whose artistic tradition looks back to the classicism of the ancient Greeks and Romans, the term “non-Western art” includes everything else. This distinction has plagued Latin American art, since—except for pre-Columbian art—it mostly fits in the category of Western art history. This categorization, however, is debatable, with some scholars positing that Latin American art is a non-Western artistic tradition that owes more to its pre-Columbian roots than to its European influences. Often, when Latin American art is discussed in a Western context, it is usually presented as derivative of European or North American art, or simply treated as the “other,” meaning different from the artistic mainstream.

This notion can be countered by exposing the many ways that artists adopted, rather than imitated, these outside influences, and by demonstrating the manner through which these forms of exchange were reciprocal—rather than unilateral—as is usually discussed. A case in point can be seen in the work of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, who are usually included in textbooks on either Western or Modern art, but whose presence is marginalized in comparison to their European and North American counterparts.

Frida (Frieda) Kahlo, Frieda and Diego Rivera, 1931, oil on canvas, 100.01 x 78.74 cm (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

A survey of non-Western art would surely include Indigenous Latin American art, but it might not include any artworks from the sixteenth century (conquest) onwards. As a result—and depending on the context in which you study Latin American art—one can end up with an entirely different and fragmented view of its artistic tradition. This is even made more complicated when considering the artistic selections in the pre-Columbian and colonial sections versus those in the Modern sections, as evidenced by the number of ritual objects (considered artworks as a result of their aesthetic qualities and craftsmanship).

Only from the broader perspective of Latin American art can individual artistic traditions be better appreciated. The plurality of meaning and the inability to neatly title or categorize Latin American art is precisely what makes this area of study so unique, and therefore interesting. A living and constantly evolving field of study, Latin American art will continue to surprise you with its multifaceted and multilayered history.

Additional resources

Several chapters in our Reframing Art History textbook offer more extended discussion of Latin American art, including:

Early South America (c. 3000 B.C.E.–2nd century C.E.)

Middle South America, c. 2nd century–c. 900 C.E.

Late South America (c. 800 C.E.–16th century C.E.)

Portuguese contacts and exchanges, c. 1400–1800

Art and Nationalism in 19th-century Latin America

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”latinamerica,”]