This is the last in a series of three essays on the World’s Columbian Exposition. For an overview of the origins and ideological underpinnings of the Fair, see the introduction. To learn more about the White City and main fairgrounds, check out the second essay.

View of the Midway Plaisance during the Chicago World’s Fair, looking east. The Ferris Wheel, at center right, was the towering attraction of the Midway, built to rival the Eiffel Tower. Also visible here is the captive balloon, a hot-air balloon that would rise and descend in place, and the pagoda-like tower of the Chinese theatre just to the left of the base of the Ferris wheel. C.D. Arnold, “World’s Columbian Exposition, Midway Plaisance,” from World’s Fair: General Views and Midway, 1893 (Art Institute of Chicago).

This essay focuses on the experience of a visitor to the Midway Plaisance, a mile-long carnival area adjacent to the main fairgrounds, featuring carnival rides, performances, food stalls, and inhabited “villages” purporting to display architecture and customs from around the world.

A human curiosity shop

The Midway Plaisance is a sort of curiosity-shop, in which the curiosities are mainly men and manners.

—Julian Hawthorne [1]

When the Fair’s boosters originally conceived of the World’s Columbian Exposition, they did not intend to set aside any space for a side show, where popular amusements and “exotic” exhibits could titillate spectators. The fair was to be what they considered “high culture” (the ideas and achievements of white westerners) without any “low-brow” (a recently coined term borrowed from phrenology, which popularized the racist idea that non-whites were less evolved, or closer to heavy-browed neanderthals) entertainments.

But the popularity of the ethnological exhibits at the 1889 Paris Exposition—not to mention its handsome profits—convinced the Chicago Fair directors to include such a space. For this purpose, they decided to reserve the Midway Plaisance, a mile-long shady pleasure drive (“plaisance”) that connected Jackson Park with nearby Washington Park. In this way, the pre-existing name, Midway Plaisance, was shortened to “midway” and entered the English lexicon as a term denoting any carnival area with games, rides, and vendors.

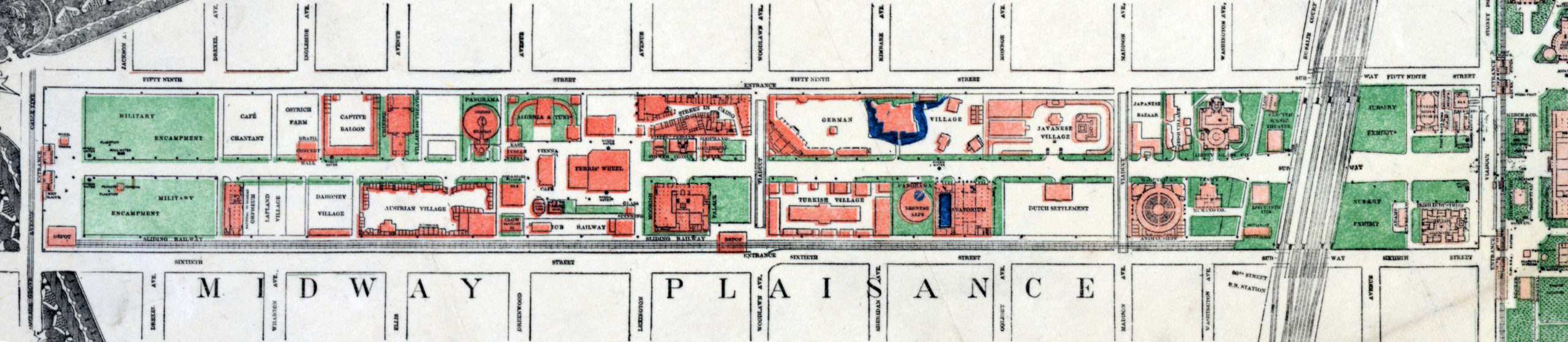

To give the Midway the sheen of educational value, the directors put Frederic Putnam, the head of the Fair’s Department of Ethnology and Archaeology, in charge. Putnam and his associates hired impresario Sol Bloom to plan the Midway’s exhibits, explaining its curious mix of spectacle and “education.” Consequently, visitors were encouraged to see the Midway not just as a carnival but as a kind of living museum of human evolution, as imagined in the racist theory of Social Darwinism then prevalent among anthropologists. At the far end of the strip were exhibits from those the Fair directors considered the “least evolved” peoples of the world (the Dahomeans and the Indigenous Americans), near the center were the “half-civilized” (Middle Easterners and Pacific Islanders), and closest to the fairgrounds were those most nearly approaching the evolutionary heights of white Americans (the Japanese, Irish, and Germans). In reality, space constraints and some turnover in attractions over the course of the Fair meant that the exhibit areas could not be so easily categorized, but the implication of the scheme was not lost on visitors. The Chicago Tribune reported that on the Midway, “an opportunity was here afforded to the scientific mind to descend the spiral of evolution, tracing humanity in its highest phases down almost to its animalistic origins.” [2]

Detail of the map of the World’s Fair, featuring the Midway Plaisance. The entrance to main fairgrounds was located on the right side. Hermann Heinze, Souvenir map of the World’s Columbian Exposition at Jackson Park and Midway Plaisance, published by A. Zeese & Co., 1893 (Library of Congress).

A visit to the Midway

If a visitor arrived at the Midway, perhaps on the day after her trip to the White City, she might be overwhelmed by the variety of sights and sounds. Unlike the white Beaux-Arts buildings of the Court of Honor, the Midway was deliberately diverse in its landscape: from the west entrance alone she may have spied an ostrich farm from California, the towers of the Chinese Theatre, a mock Bedouin encampment, and painted reindeer adorning the entrance to Lapland village. A mile long and six hundred feet wide, the Midway included popular amusements along with pavilions constructed by national delegations. Most shows and exhibits charged an additional entrance fee, as opposed to the White City exhibitions, which were free with an entrance ticket.

For many visitors, the Midway was the real attraction of the World’s Fair. Those looking for thrills could ride the 264-foot high Ferris wheel (the first ever engineered on such a scale, built by George Washington Gale Ferris himself), ascend in a captive hot air balloon, or zoom around on the refrigerated “ice railway” (toboggan roller coaster). The Midway also offered an education (of questionable accuracy) in world cultures, with food, exhibits, and performances from countries that both were, and were not, officially represented within the White City. Several nations sent delegations to inhabit “villages” where they would exhibit their homes, style of dress, and customs to visitors, while selling food and merchandise.

The western end of the Midway: The Wild West, the Wild East, and Dahomey village

Exterior of the Sitting Bull exhibit, topped by a stuffed buffalo. The paintings on the exterior depict both “Custer’s Last Stand” at the Battle of Greasy Grass and the death of Sitting Bull outside his cabin. “Entrance to Sitting Bull’s Log Cabin, Midway Plaisance,” 1893 (Chicago00).

It’s possible that our visitor may have come to the Midway after taking in a performance at Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World, a touring rodeo of cowboys, Indigenous Americans, and sharpshooters that was unaffiliated with the World’s Columbian Exposition but located a few blocks away from the Fair. The showman and entrepreneur Buffalo Bill had originally intended to exhibit at the Midway but balked when the Fair’s organizers demanded 50% of his profits. They would bitterly regret their decision not to negotiate a smaller cut after the Wild West show’s six-month run reportedly raked in a million dollars, the equivalent of $30 million in 2021 dollars. [3] Among other acts, the Wild West show offered reenactments of famous battles of the Indian Wars, which cast Plains peoples as savages whose attacks on white settlers and the U.S. military must be avenged by white frontiersmen.

Within the Midway, exhibitors tried to capitalize on the popularity of the Wild West show by adding both a “Wild East Show” (featuring trick riders from North Africa and the Middle East) and a display of Sitting Bull’s Log Cabin. The cabin—disassembled and transported from its South Dakota location after Sitting Bull’s death at the hands of police—reinforced the idea that Indigenous Americans had been conquered, along with the frontier, and what had been theirs was now the property and even plaything of white Americans. The parade of symbols showing defeated Indigenous people reinforced the Fair’s overall message that Manifest Destiny in North America was complete.

If our visitor progressed, the next most notable exhibit she would encounter was the Dahomean village, where more than 100 Fon people from the Kingdom of Dahomey demonstrated music, dance, and religious rituals. Amid the Second Franco-Dahomean War, a French impresario named Pené brought the Dahomeans as an exhibit to Chicago. Known for their fierce female warriors—often called ‘Amazons’ in popular culture—and for their rumored cannibalism, the ethnology department felt that the Dahomeans would serve as an example of the state of nature from which humanity had arisen. The Chicago press portrayed the Fon as savages, “blacker than buried midnight and as degraded as the animals which prowl the jungles of their dark land,” and they were frequent targets of racist caricature, depicted as the least-evolved people at the World’s Fair. [4] At the far end of the Midway, billed as a carnival attraction, the Dahomeans were cast as the antithesis of everything that the White City represented.

Exterior view of the Dahomey Village, with painted advertisements depicting Dahomean men and women wielding weapons. C.D. Arnold and H.D. Higinbotham, Dahomey Village—On the Midway, in Official Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893.

Two Dahomean men. The man on the left is dressed in an American flag and jacket, while the man on the right wears traditional clothing. “From Far Away Dahomey,” 1893 (Friends of the White City).

The center of the Midway: rides and orientalist spectacles

The Ferris wheel was the monumental attraction of the Chicago World’s Fair. Standing 264 feet tall, its cars could each hold up to 60 people at a time. Approximately 38,000 passengers rode the Ferris wheel each day it operated. Also visible in this photograph is the ice railway in the right foreground, the dome of the Moorish Palace, and some of the minarets of Cairo Street. C.D. Arnold and H.D. Higinbotham, The Ferris Wheel, in Official Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893.

Not everything on the Midway was intended to be an object lesson in Social Darwinism. Past the Dahomey village our visitor could see a panorama of the eruption of Kilauea (the U.S.-backed coup of the Hawaiian throne in January 1893, still being contested that summer, had increased white Americans’ interested in the island nation), ride the enormous Ferris wheel or the ice railway, or stop into the Zoopraxigraphical Hall, the world’s first commercial motion picture theater, where Eadweard Muybridge gave lectures on locomotion and demonstrated moving pictures on his “zoopraxiscope.”

But this central part of the Midway was also devoted to North Africa and the Middle East, with an Algerian and Tunisian village, a Moorish Palace, and Egypt’s popular Midway attraction, Cairo Street. Cairo Street aimed to immerse visitors in an Egyptian streetscape featuring houses, shops, a Temple of Luxor replica, and a mosque topped with a minaret (thought to be one of the first mosques in the United States, it was a site of worship for the Muslim citizens who worked at the Fair in addition to a landmark). Visitors could ride camels, see a simulated wedding procession, and view a belly dancer called “Little Egypt,” whose “hootchy-kootchy” dance became an international sensation. These exhibits contrasted an orientalist view of the east as exotic, sexualized, unchanging, and superstitious, against the rational, chaste, developed, and pious West exemplified by the White City.

The eastern end of the Midway: Pacific and European connections

As our visitor drew closer to the White City, there were villages celebrating Europe: a German village and an Irish village featuring a replica of Blarney Castle. These were interspersed with a Javanese village, a Samoan village, and a Japanese bazaar. Unlike the Dahomeans, the Javanese were lauded in the American press as friendly and hardworking, but childlike. (Japan, like its European counterparts, had both an official national pavilion in the main fairgrounds and a village on the Midway thanks to its early and enthusiastic participation in the Fair; China, whose government understandably resented the U.S. Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, had refused to participate, and the Chinese village on the Midway was operated by Chinese Chicagoans who saw the Fair as an opportunity to promote cultural understanding). [5] The incorporation of Japan reflected U.S. interests in the newly open nation, while the positive, if patronizing, images of the Samoans in the American press helped to lay the groundwork for popular support of annexing American Samoa in 1899.

Samoan performers singing in front of a dwelling. (Friends of the White City)

There was a certain logic to this combination of European and Pacific nations: the former—especially the Irish and Germans—were the most recently assimilated ethnicities in the American body politic. The latter were among the nations with whom the U.S. government was most keen to open trade relationships, and whom they eyed as potential imperial subjects. Each was next door to the grand celebration of American cultural and industrial might that was the White City, but remained separate.

Conclusion: “The World as Plaything”

Julian Hawthorne, son of Nathaniel and keen cultural critic, claimed that the Midway should be named “The World as Plaything,” a set of humans, landscapes, and objects that invited American visitors to view them as toys. [6] Although the Fair’s promoters had not originally intended to include the Midway attractions, they were integral to the narrative of evolution and empire at the Chicago World’s Fair. Within the main fairgrounds was the “civilized” world, capped by the homogenous order of the Court of Honor, which represented what the Fair directors considered the highest achievements of men and whose architecture looked back to ancient Greece and Rome to claim the heritage of western civilization. Outside was the deliberately disordered Midway, with its carnival barkers, jumble of architectural styles, and exoticized cultures. And all of it was for sale, or there for the taking, encouraging white visitors to view the resources and lands of Asia, Africa, and the Americas as theirs for the taking.

Just five years after the World’s Fair and the Midway closed in 1893, the United States expanded its empire outside the bounds of North America, formally annexing Hawai’i (after staging a coup that deposed Hawaiian Queen Liliuokalani in 1893) and taking possession of former Spanish colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific after its victory in the Spanish-American War. Was it a coincidence that the United States, having claimed ownership of Christopher Columbus’s mantle with its World’s Columbian Exposition, now claimed the lands his voyages had brought into the Spanish empire? Or that the people of Cuba, Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the Philippines found themselves part of an American empire that would cast them as members of a permanent sideshow, adjacent to but never able to enter the white city of Washington, D.C.? Perhaps, but the Chicago World’s Fair certainly primed white Americans to think in these terms as it transitioned from one frontier to the next.

Notes

- Julian Hawthorne, “The Lady of the Lake,” Lippincott’s Magazine, Aug 1893.

- “Through the looking Glass” Chicago Tribune 1 Nov 1893, 9, quoted in Robert Rydell, All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916 (University of Chicago Press, 1984), p. 65

- Joy S. Kasson, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: Celebrity, Memory, and Popular History (Hill and Wang, 2000), p. 129.

- Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, p. 66.

- Huping Ling, Chinese Chicago: Race, Transnational Migration, and Community since 1870 (Stanford University Press, 2021), p. 63.

- Hawthorne, “Foreign Folk at the Fair,” Cosmopolitan Magazine, 15 (1893), pp. 569- 570, quoted in Rydell, All the World’s a Fair, p. 64.

Additional resources

Walk down the Midway with the Chicago 00 Project