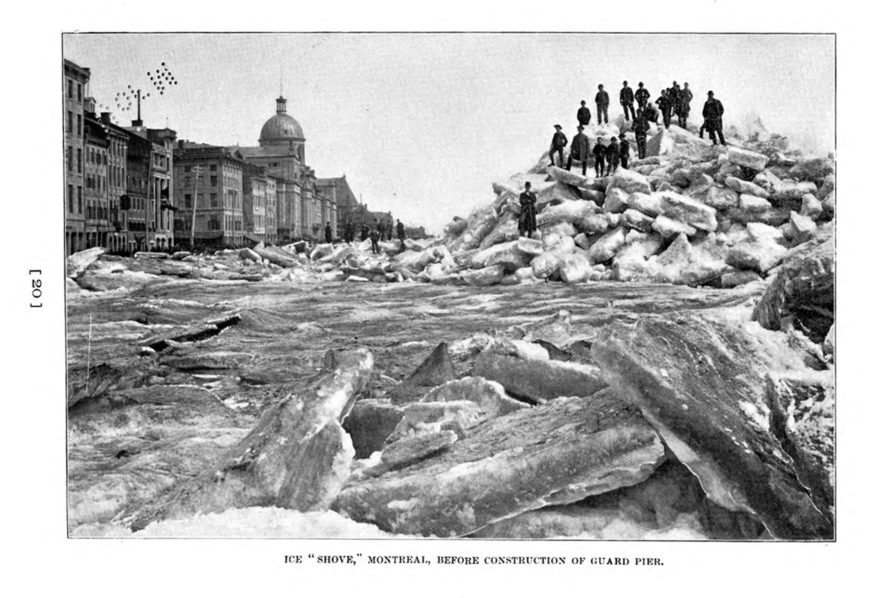

William Notman, Ice Shove, Commissioner Street, Montreal, 1884, silver salts on glass, gelatin dry plate process, 20 x 25 cm (VIEW-1498, McCord Museum, Montreal, Quebec)

The movement of winter ice is so powerful that it can physically change the shape of waterways, destroy entire harbors, block key economic trade routes, and in the most devastating instances, take human life. One of the more spectacular forms of movement is an ice shove, which follows the total ice blockage of a river. Upward pressure from the rising water level behind the blockage forces the ice to suddenly and rapidly jut, or shove, outward. As water levels recede, they leave behind both the piled ice and a hollowed area underneath. But, perhaps the greatest power of this natural force is the way it captures the popular imagination with equal parts wonder and fear as it is photographed and circulated in images such as William Notman’s Ice Shove, Commissioner Street, Montreal from 1884.

A harbour frozen over

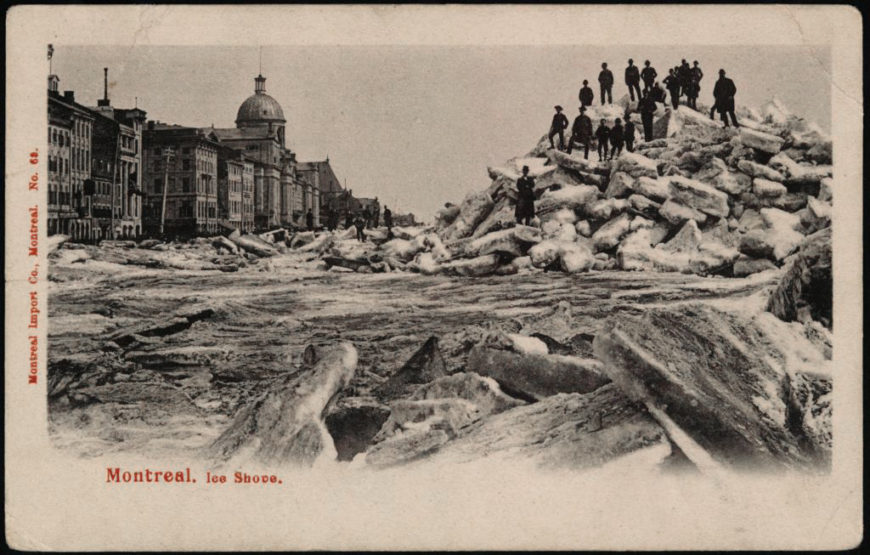

In Notman’s Ice Shove, large pieces of protruding ice fill the foreground as a massive rupture of the ice shove juts into the sky on the right side of the photograph. Posed atop that ice shove are more than a dozen indistinguishable figures standing triumphantly, as though they had summited a mountain peak. The small size of the figures reveals the enormity of the shove, which appears to reach the scale of the buildings along the left edge of the image. The ice pushes directly against the stone buildings that run the length of the port, emphasizing the harbour front’s close call with total destruction.

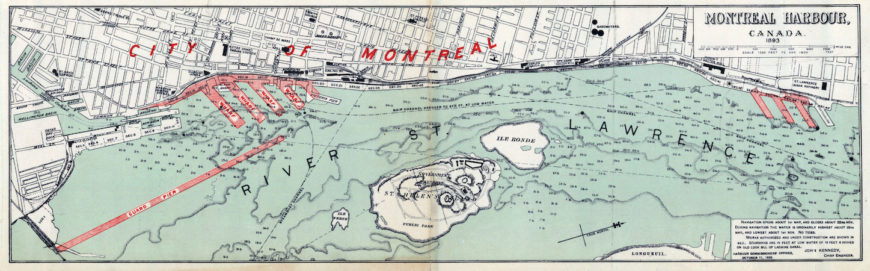

Map of Montreal Harbour, 1893 (Port Montreal)

Throughout the nineteenth century, from December to May, the port in Montreal, Quebec, along the Saint Lawrence River, was blocked by ice and closed to shipping. While the economic heart of the city came to a frozen standstill, the ice gained popularity as a tourist attraction for those who were tempted by its danger and wanted to view its impressive formations. The shoves were a subject of wonder and fascination for the city’s residents, but also for people who were curious about the dramatic stories of damage and peril. Photographs like Notman’s offered viewers the ability to tour the shoves for themselves, just as we see those doing in the photograph, and were reproduced in many formats—books, magazines, newspapers, pamphlets, albums, keepsakes, and especially postcards—that circulated the images as far as the postal service could take them. Spectacular ice shoves warranted the effort of hauling cumbersome photographic equipment, including a heavy, large-format camera and tripod, as well as glass negatives and photographic chemicals, out into the elements—not just once, but every year that the ice shove occurred in the port.

Notman and internationalism

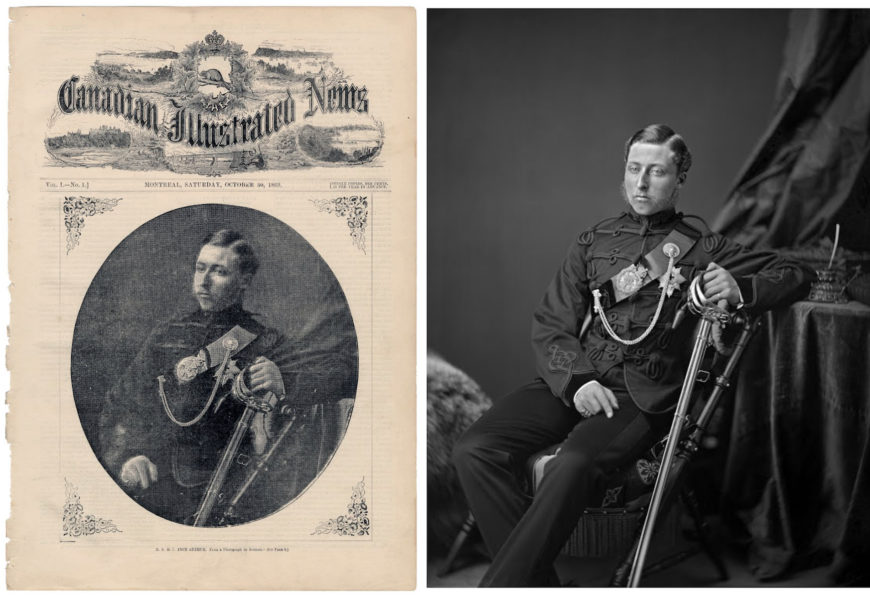

Scottish-born, Montreal-based photographer Notman operated a prolific studio business that catered to a range of photographic needs—from portraiture to collectible landscape scenes. The ice shove was a subject that he photographed several times as it occurred in the port throughout the years, a spectacular site that was sure to be of interest to his clientele. His photographs were brought to the attention of Queen Victoria after Notman photographed her son, the prince of Wales in 1860. Soon after, Notman touted himself as “Photographer to the Queen,” which he had inscribed into the stone over his studio doors as a way to bolster his reputation. By 1865 he had set up studio branches throughout Canada and into the United States. As a result, he was among the first Canadian photographers to gain an international reputation.

William Notman & Son, Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill, Montreal 1885, silver salts on glass, gelatin dry plate process, 17 x 12 cm (McCord Museum, Montreal, Canada)

Like other commercial photographers in the late nineteenth century, Notman also photographed celebrities and events of public interest—including Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show that made a stop in Montreal in 1885 on its nearly thirty-year tour of North America and Europe. In Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill, Notman famously captures Hunkpapa Lakota (Sioux) leader and former warrior-turned-performer Sitting Bull along with legendary plainsman and showman William “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

Left: Prince Arthur William Patrick Albert, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, Montreal, QC, Canadian Illustrated News (30 October 1869); right: William Notman, Albert, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, Montreal, QC, 1869, silver salt on glass, 25 x 20 cm (McCord Museum, Montreal)

Picturing a precarious port: the circulation of photographs

On Oct. 30, 1869, Notman’s portrait of Prince Arthur appeared on the front page of the inaugural issue of Montreal’s Canadian Illustrated News. The photograph was reproduced as a Leggotype, a halftone printing process that enlarged, reduced, or reversed photographs for print publication in a way that would simulate a continuous gradation of tone. This technological feat cleared the way for highly detailed photographic reproduction to reach a wide-ranging audience through printed newspapers and periodicals.

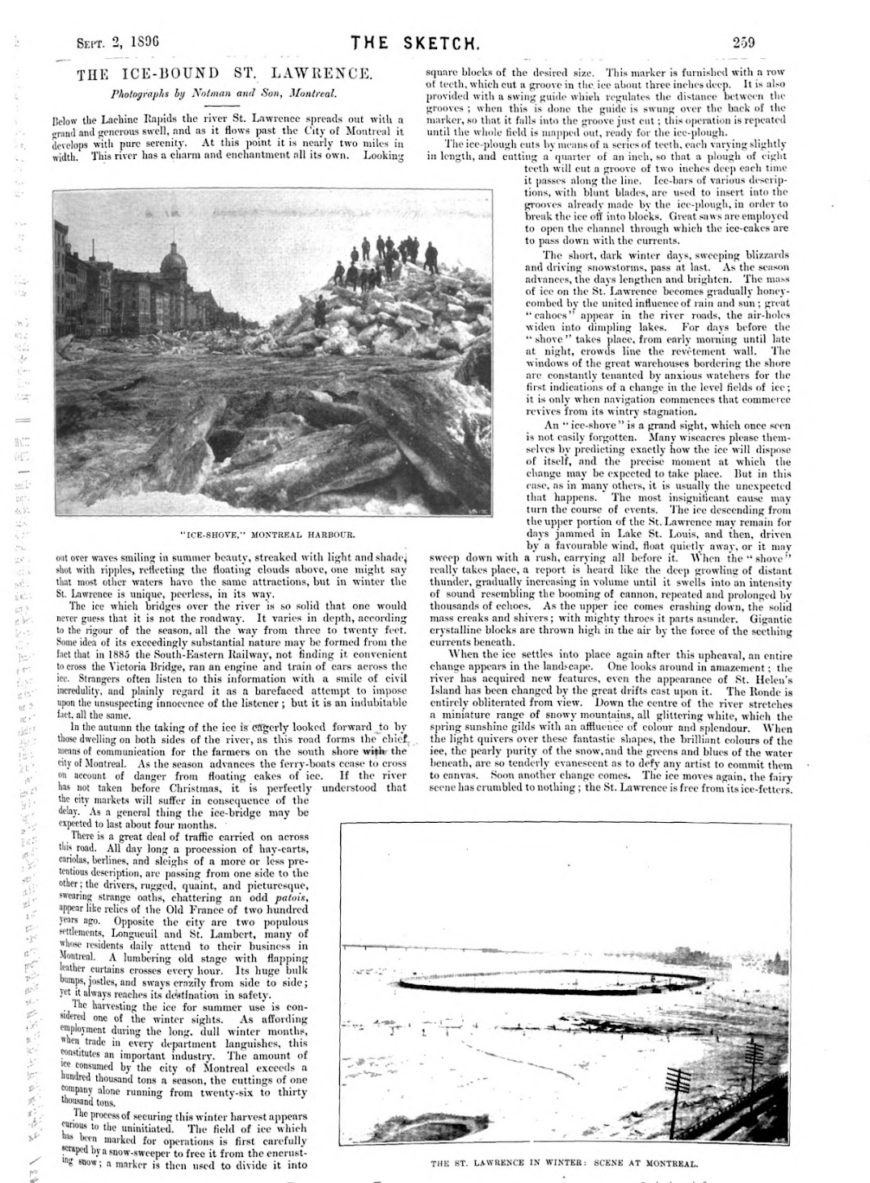

“The Ice-Bound St. Lawrence,” The Sketch 188.15 (September 2, 1896), p. 259

Decades later, Notman’s 1884 photograph of the ice shove was printed in the September 1896 issue of The Sketch, a popular British illustrated magazine, to accompany the story “The Ice-Bound St. Lawrence.” It casts the winter port vividly, with wonder and nostalgia:

Down the center of the river stretches a miniature range of snowy mountains all glittering white, which the spring sunshine gilds with an affluence of colour and splendour. When the light quivers over these fantastic shapes, the brilliant colours of the ide, the pearly purity of the snow, and the greens and blues of the water beneath are so tenderly effervescent as to defy any artist to commit them to canvas.“The Ice-Bound St. Lawrence,” The Sketch (September 2, 1896) [1]

Notman’s photo of the ice shove, p. 20 in Thomas C. Keefer, Ice floods and winter navigation of the lower St. Lawrence,… (Ottawa: J. Hope & sons, 1898)

In addition to The Sketch, which described the shove’s spectacular presence and beauty, Notman’s photograph also appeared in a government report (by Thomas C. Keefer) to demonstrate and document the disaster, as well as on postcards (such as the one below) produced by a variety of manufacturers over the next decade.

“Montreal, Ice Shove,” postcard, Montreal import Co. (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

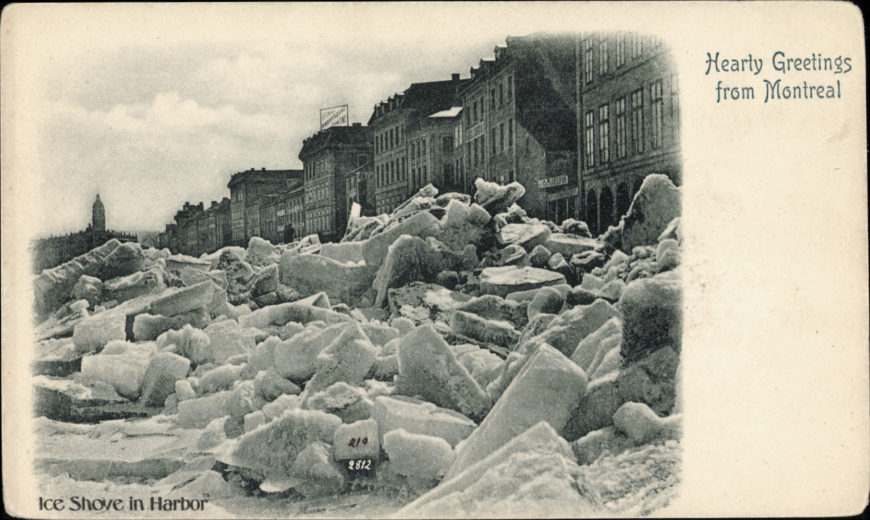

A similar postcard with a photograph taken by Notman of the ice shove in 1875 not only indicates an enduring interest in the phenomenon of the ice shove, but also a reflection of something quintessential about Montreal’s resilience as a community with its caption: “Hearty Greetings from Montreal.”

“Hearty Greetings from Montreal, ice shove in Harbor,” 1875, postcard (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec)

Photographs such as Notman’s offered spectacular views of popular events and scenes while also providing a way for people to imagine the failure or success of a Canadian city’s ability to cope with the forces of nature.

Notes:

[1] “The Ice-bound St. Lawrence.” The Sketch 188.15 (September 2, 1896), p. 259.

This essay is brought to you through a partnership with Open Art Histories.

This essay is brought to you through a partnership with Open Art Histories.

Additional resources:

Demonstration of halftone process

Sarah Parsons, “William Notman, Life & Work,” (2013–2014).

Port Montreal, “Where were the first port operations located in Montreal?”

“The Ice-bound St. Lawrence,” The Sketch 188.15 (September 2, 1896).

Douglas Borthwick, History of Montreal, Including the Streets of Montreal. Their Origin and History. (Montreal: D. Gallagher, 1897).

Elizabeth. Cavaliere, “Flood Watch: The Construction and Evaluation of Photographic Meaning in Alexander Henderson’s Snow and Flood After the Great Storms of 1869,” in The Photograph and the Collection, ed. Graeme Farnell (Edinburgh and Boston: Museums Etc., 2013), pp. 244–267.

Charles N. Forward, “The Development of Canada’s Five Leading National Ports.” Urban History Review 10, no. 3 (February, 1982), pp. 26–27.

Jason Gilliand, “Muddy Shore to Modern Port: Redimensioning the Montréal Waterfront Time-Space.” The Canadian Geographer 48, no. 4 (2004), pp. 463–465.

David Harris, “Alexander Henderson’s Snow and Flood after Great Storms of 1869.” Revue d’Art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 16, no. 2 (1989), pp. 155-160, 262–272.

Jeffrey H. Jackson, “Envisioning Disaster in the 1910 Paris Floods.” Journal of Urban History vol. 37, no. 2 (December 2010), pp. 176–207.

Thomas C. Keefer, “Ice Floods and Winter Navigation of the Lower St. Lawrence” in From the Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada. Second Series 1898–99 Volume 4 Section 3. (Ottawa: J. Hope & Sons; Toronto: The Copp-Clark Co., 1898), pp. 6–7.

Sarah Parsons, William Notman: Life and Work (Toronto: Art Canada Institute, 2014).

Joan M. Schwartz, “Documenting Disaster: Photography at the Desjardins Canal, 1857.” Archivaria 25 (January 1987), pp. 147–54

Thomas C. Keefer. “Ice Floods and Winter Navigation of the Lower St. Lawrence.” In From the Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada. Second Series, volume 4, section 3 (Ottawa: J. Hope & Sons; Toronto: The Copp-Clark Co., 1898), pp. 3–17.

Stanley Triggs, William Notman: The Stamp of a Studio (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario / Coach House Press, 1895).