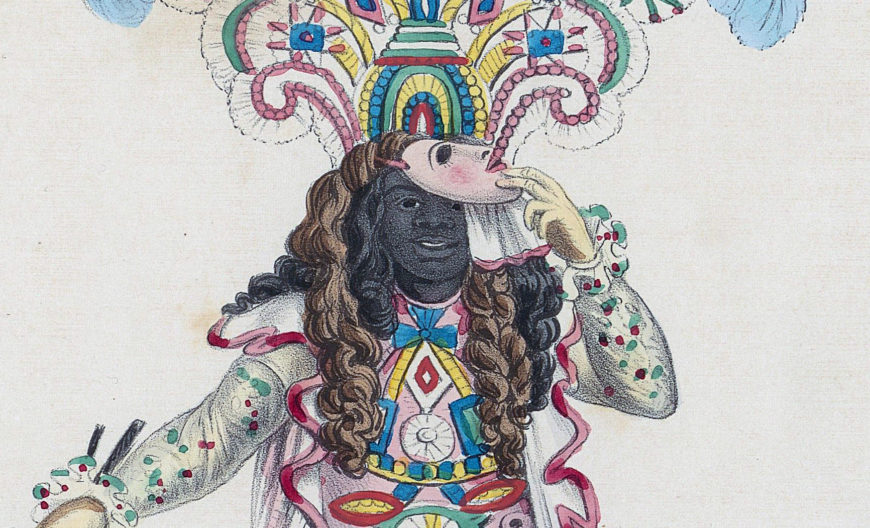

Isaac Mendes Belisario, “Koo Koo, or Actor Boy” from Sketches of Character, In Illustration of the Habits, Occupations, and Costume of the Negro Population in the Island of Jamaica, 1837–38, hand-painted lithographic print (Yale Center for British Art)

Crowned by feathers and draped in color, a young Black man lifts his mask and smiles at the viewer. He wears an auburn wig over his own dark tresses as he shows off his outfit. This image is included in Isaac Mendes Belisario’s Sketches of Character, In Illustration of the Habits, Occupations, and Costume of the Negro Population in the Island of Jamaica, published in Kingston, Jamaica between 1837 and 1838. This ambitious series (which appeared in three installments) focused on Jamaica’s Black population, particularly their carnival traditions and occupations. It was produced during apprenticeship, the four-year period (1834–38) between the abolition of slavery and full emancipation, where enslaved people in Jamaica became laborers known as apprentices and engaged in the same work they did for their former enslavers. This transition could have inspired Belisario to record important aspects of Black life and cultural expression.

Sketches of Character

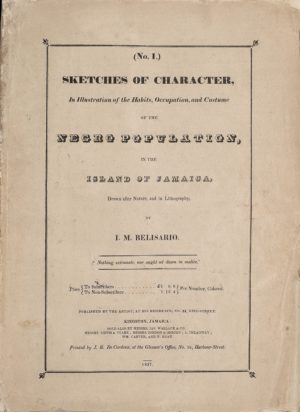

Isaac Mendes Belisario, cover, No. 1, Sketches of Character, In Illustration of the Habits, Occupations, and Costume of the Negro Population in the Island of Jamaica, 1837–38, hand-painted lithographic print (Yale Center for British Art)

In the three print installments of Sketches of Character, we find a total of twelve hand-painted, lithographic prints accompanied by text written by the artist. In the preface to the first publication, Belisario states his intentions to create a faithful representation of his subjects and their habits. He alludes to the possible future loss of these traditions due to the island’s rapidly changing society. He also noted that he wished to avoid caricature. [1] While Belisario refrains from sharing his personal views on emancipation, he attempts to frame his subjects in a positive light. Belisario, a white Jewish man, seems aware of the prevalence of racial caricature at the time and its role in propagating prejudice and stereotypes, yet at times he draws on the racist visual and linguistic codes he appears to wish to escape.

Most of the prints that comprise Sketches of Character are focused on different carnival and masquerade customs that developed among the enslaved population. By the late 18th century, these had become part of the Christmas and New Year’s public celebrations and were a staple of holiday events in Jamaica. In many places of the Americas, Christian carnivals and feasts became settings for syncretism. The local population, including Indigenous peoples and those of African ancestry, converged around carnival, creating or appropriating traditions, adding elements and significance of their own. Participants mostly made their own costumes, buying the materials themselves or with the assistance of sponsors, and organized themselves into character and event troupes for the parades. The first two installments in the series are almost exclusively dedicated to this subject, providing illustrations of the costumes; the order in which groups of characters, dancers, and musicians paraded; and the activities they engaged in.

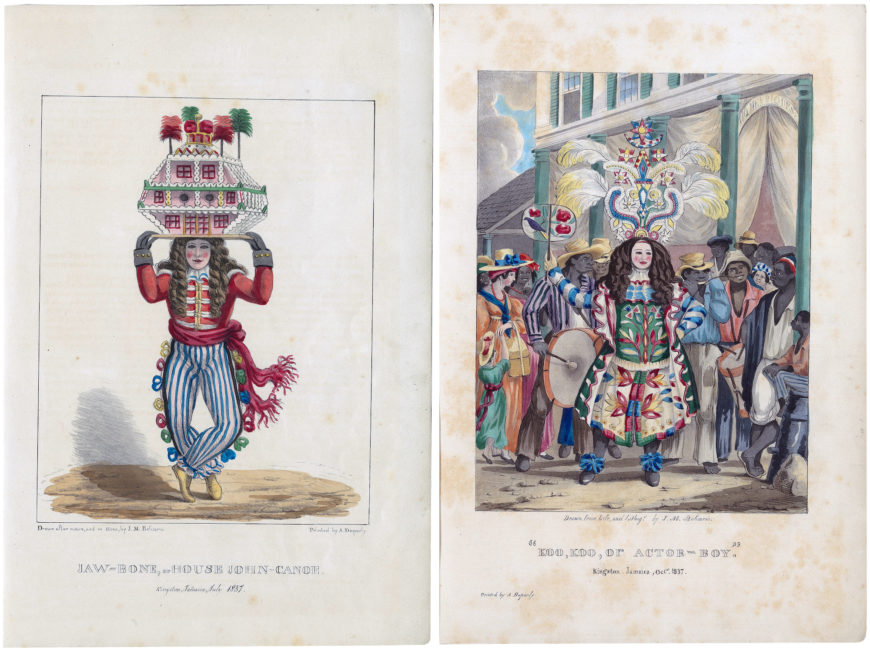

Isaac Mendes Belisario, “Jaw-Bone, or House John Canoe” (left) and “Koo Koo, or Actor Boy” (right) from Sketches of Character, In Illustration of the Habits, Occupations, and Costume of the Negro Population in the Island of Jamaica, 1837–38, hand-painted lithographic prints (Yale Center for British Art)

Two of the most striking figures are “Jaw-Bone, or House John Canoe”, and “Koo Koo, or Actor Boy,” two characters whose costumes combine visual and cultural aspects from both African and European traditions. John Canoe was part of the Jonkonnu masquerade, which has roots in West African religious practices from the Igbo, Yoruba, and Ga cultures, which still held religious significance through slavery and the 19th century. He wears a military jacket and sash, striped pants, and a long curly wig and is represented mid-dance, balancing an impressive headdress shaped like a colonial manor with a crown and palm trees. In the text Belisario points to Merry Andrew, a jester-type character from British theater tradition, as a possible reference.

Actor Boy was part of another celebration, where performers engaged in theatrical competitions reciting Shakespeare and also participated in costume competitions. Actor Boy wore extravagant clothes and combined European accessories, including long wigs and fans that look back to the 18th century, with elaborate headdresses and textiles drawn from Kongolese traditions. [2]

Detail, Isaac Mendes Belisario, “Koo Koo, or Actor Boy” from Sketches of Character, In Illustration of the Habits, Occupations, and Costume of the Negro Population in the Island of Jamaica, 1837–38, hand-painted lithographic print (Yale Center for British Art)

Both John Canoe and Actor Boy wear whiteface masks. These could stem from Kongolese rituals, where white masks were used to indicate the presence of ancestral spirits through the characters. [3] The use of white masks and European accessories also allowed the performers to subvert the racial and cultural boundaries that defined British colonial society.

These appropriations speak to the freedom found in the context of carnival, which historically has been a moment where social norms and boundaries blur and are turned on their heads. The masquerades were both a method of relief and resistance for the Black population against a violent colonial system. Black participants could openly rejoice in their traditions while pushing back at a system that oppressed them, combining cultural references that allowed them to express themselves and protest their condition. [4] Dances and character troupes were often financed by white, free Black, and mixed people (both individuals and groups of people sponsoring troupes). [5] Carnival spoke to Jamaican society at large, with all sectors participating in one way or the other and the costumes and dances fascinated revelers and observers—including Belisario.

Isaac Mendes Belisario, “Red Set Girls and Jack in the Green” from Sketches of Character, In Illustration of the Habits, Occupations, and Costume of the Negro Population in the Island of Jamaica, 1837–38, hand-painted lithographic print (Yale Center for British Art)

The intermingling of African and European costumes is present in another illustration entitled “Red Set Girls and Jack in the Green,” which shows a group of five female figures who participated in dancing competitions with other Set Girls. Their style is modeled on European dress, here represented in a stylized manner by the artist. Their colorful ensembles are based on the fashionable silhouettes of the early 1830s, with puffy sleeves decorated with ribbons and topped with straw hats and pink feathers. They are accompanied by an impressive figure completely covered in palm fronds, named in the title, Jack in the Green is reminiscent of the Jack in the Green found in May Day celebrations in England (where a character covered in green foliage accompanied milkmaids and chimney sweepers in their parades). [7] The full body costume is also suggestive of those used for the figures of Egungun and Zangbeto, from Yoruba and Ogu festivals respectively.

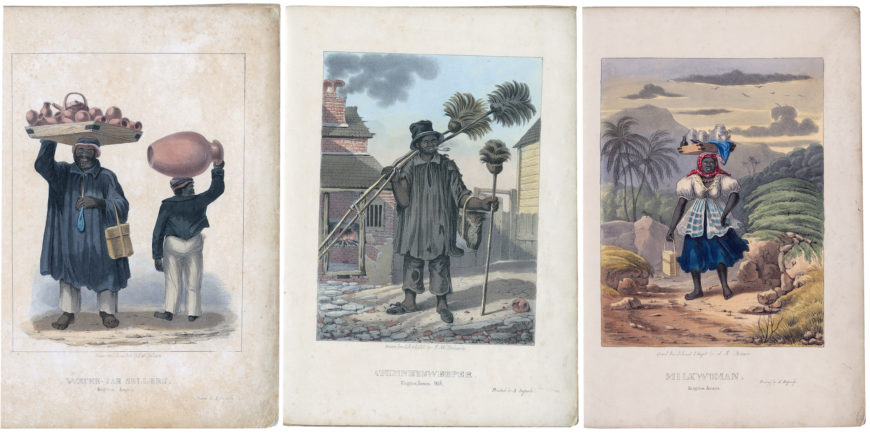

Isaac Mendes Belisario, “Water-Jar Sellers,” “Chimney Sweeper,” and “Milkwoman” from Sketches of Character, In Illustration of the Habits, Occupations, and Costume of the Negro Population in the Island of Jamaica, 1837–38, hand-painted lithographic print (Yale Center for British Art)

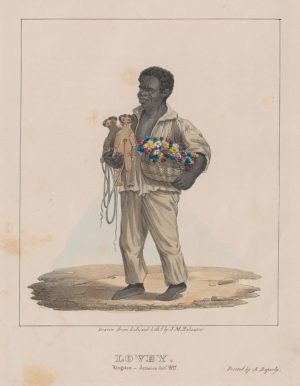

Isaac Mendes Belisario, “Lovey,” from Sketches of Character, In Illustration of the Habits, Occupations, and Costume of the Negro Population in the Island of Jamaica, 1837–38, hand-painted lithographic print (Yale Center for British Art)

The third (and final) installment is focused on what the artist describes as the “Cries of Kingston.” These five images show some of the occupations of the Black population, such as water-jar sellers, a chimney sweeper, and a milkwoman. These are represented as figural types in compositions not dissimilar to those found in the Cries of London publications, which seem to be Belisario’s main artistic reference.

The only portrait in the series depicts a man named Lovey. The 51-year-old apprentice, originally named Kangga and who was from Congo, was a well-known vendor and puppeteer. While Belisario presents Lovey sympathetically in his written description, the portrait veers into caricature. He portrays Lovey in an almost child-like body, with exaggerated facial features. Here and in other illustrations, like “Creole Negroes,” the artist stumbles in his objective. The pervasiveness and impact of visual and written stereotypical models from ethnological and folklore publications become apparent.

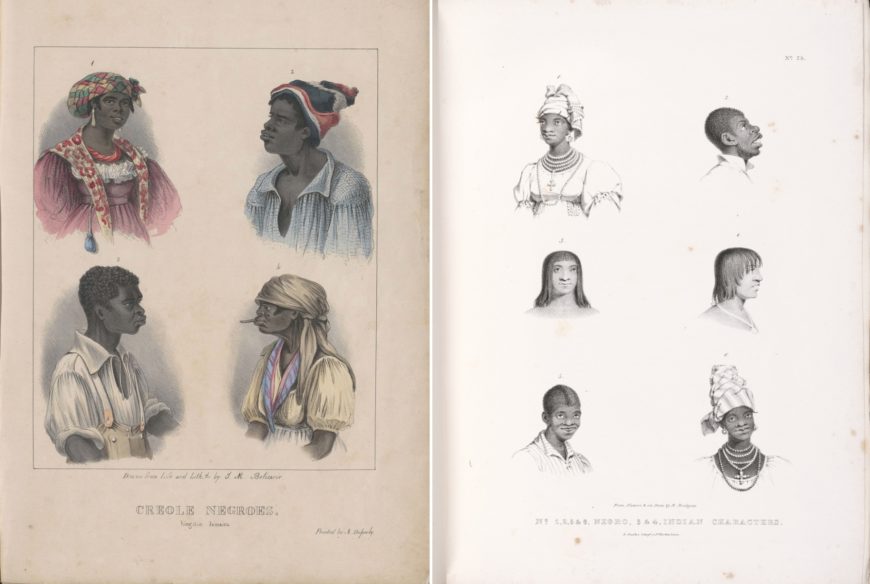

Left: Isaac Mendes Belisario, “Creole Negroes,” from Sketches of Character, In Illustration of the Habits, Occupations, and Costume of the Negro Population in the Island of Jamaica, 1837–38, hand-painted lithographic print (Yale Center for British Art); right: Richard Bridgens, West India scenery: with illustrations of Negro character, the process of making sugar, &c. from sketches taken during a voyage to, and residence of seven years in, the island of Trinidad (London: Robert Jennings & Co., 1836) (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library)

The composition for “Creole Negroes” is similar to the ethnographic prints that appeared in Richard Bridgens’s West Indian Scenery (1836) which focused on Trinidad and plantation life. Bridgens espoused pro-slavery and racist views both through word and illustration, and used ethnographic language to describe the perceived inferiority of those of African ancestry.

By comparison, Belisario’s Sketches often comes across as ambivalent about its subjects, and he is not explicitly pro- or anti-slavery in the text. At times he describes the figures as “primitive” and “savage,” using the language of contemporaneous racist publications he is clearly familiar with. However, this contrasts with his interest in the traditions and people that inspired his publication—particularly the sections devoted to carnival. “Creole Negroes” and his portrait of Lovey are deeply racist, while many of the carnival illustrations seem more positive and genuine. Sketches often results in an ambiguous reading. His stated intentions may have been different from a work like Bridgens’s, but Belisario does not fully reject some of these racist ideas.

Belisario worked on Sketches at a decisive moment in Jamaica, between the abolition of slavery in 1833 and the culmination of apprenticeship. [8] Its publication may reflect the optimism of many people toward the end of apprenticeship; a feeling not shared by all, especially anti-abolitionists, and plantation owners whose businesses depended on enslaved labor. Economic anxieties amongst this sector, racism, and legal measures to control and keep the newly freed population in slave-like labor were the cause of immense social and political tension between 1834 and 1838.

A life between Kingston and London

Born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1795 to a Sephardic Jewish family, Belisario spent much of his youth in London. He studied under English landscape painter Robert Hills between 1815 and 1818. Yet he worked primarily as a stockbroker, maintaining a side practice as a portraitist and exhibiting in the Royal Academy in 1831.

He moved back to Jamaica around 1832, where he dedicated himself to an artistic career. His return seems to have been motivated by health concerns and perhaps by the passing of the Jewish Emancipation Act by the Jamaican Assembly, which granted the Jewish population full civil liberties, six months after free people of color had achieved the same rights. [9] Belisario remained on the island for the next 15 years.

Belisario produced portraits and landscapes for members of Jamaica’s upper class. His paintings for plantation owners pull from the English picturesque tradition that appealed to landowners in the colonies. His compositions for the Marquess of Sligo, like that of his Cocoa Walk Estate, are picturesque renderings of idyllic plantations. These images were far-removed from the harsh reality experienced by plantation laborers whose conditions had not significantly improved since abolition. These landscapes tend to be panoramic views of the planter’s property, showcasing their dominion over the land and the figures that inhabit it. Black figures tend to be few and are represented at a distance and in the context of the planter’s property.

Belisario’s interest in the lives of the Black population and masquerade may speak to his experience as a Jewish man in British society. While considered white, Jews in Jamaica suffered social and legal marginalization since the time of the Spanish occupation. Discriminatory legislation had long limited their political and economic development. Until recently they couldn’t participate in government, vote, or join the military. Jews and their businesses in Jamaica were also heavily taxed in comparison to other groups until the 1820s. While they could have servants and enslaved peoples, there were measures to control how many; this limited their involvement in the plantation economy, but they participated in the slavery auction system.

Belisario was likely descended from Conversos, and was therefore deeply aware of the ways he and his family had to negotiate their Jewishness in a Christian society. [10] These experiences could have attracted him to the Jamaican masquerades, as its very nature disrupted social boundaries. While his stance on slavery is unknown, the fact that this series exists and his commissions from the Marquess of Sligo and Chief Justice Joshua Rowe, who both had abolitionist sympathies, may point to the artist’s anti-slavery sentiments. [11] The ambivalence evident in Sketches of Character on the matter of emancipation may come from both an attempt to not alienate his white, Christian clientele and to advance himself and the Jewish community in Jamaica. [12]

Detail showing Actor Boy in front of the shop owned by Miguel Q. Henriques, Isaac Mendes Belisario, “Koo Koo, or Actor Boy” from Sketches of Character, In Illustration of the Habits, Occupations, and Costume of the Negro Population in the Island of Jamaica, 1837–38, hand-painted lithographic prints (Yale Center for British Art)

Jewish businesses had been closely linked to Jonkonnu and the enslaved population for decades before abolition, providing costume supplies and other essentials. Since Jews observe Shabbat on Saturdays, they were able to open their stores on Sundays, which allowed those enslaved to patronize their establishments on their day off. [13] Belisario includes one of these shops in his illustration of the winning Actor Boy of 1836. Here, the parade stopped in King Street before the entrance of the store of Moses Q. Henriques, a Jewish merchant and friend of the artist, where many shopped for the textiles used for their costumes. [14] The syncretism and expression of Jamaican masquerades in the 19th century, as represented by Belisario, captures the complex interconnections of its diverse society.