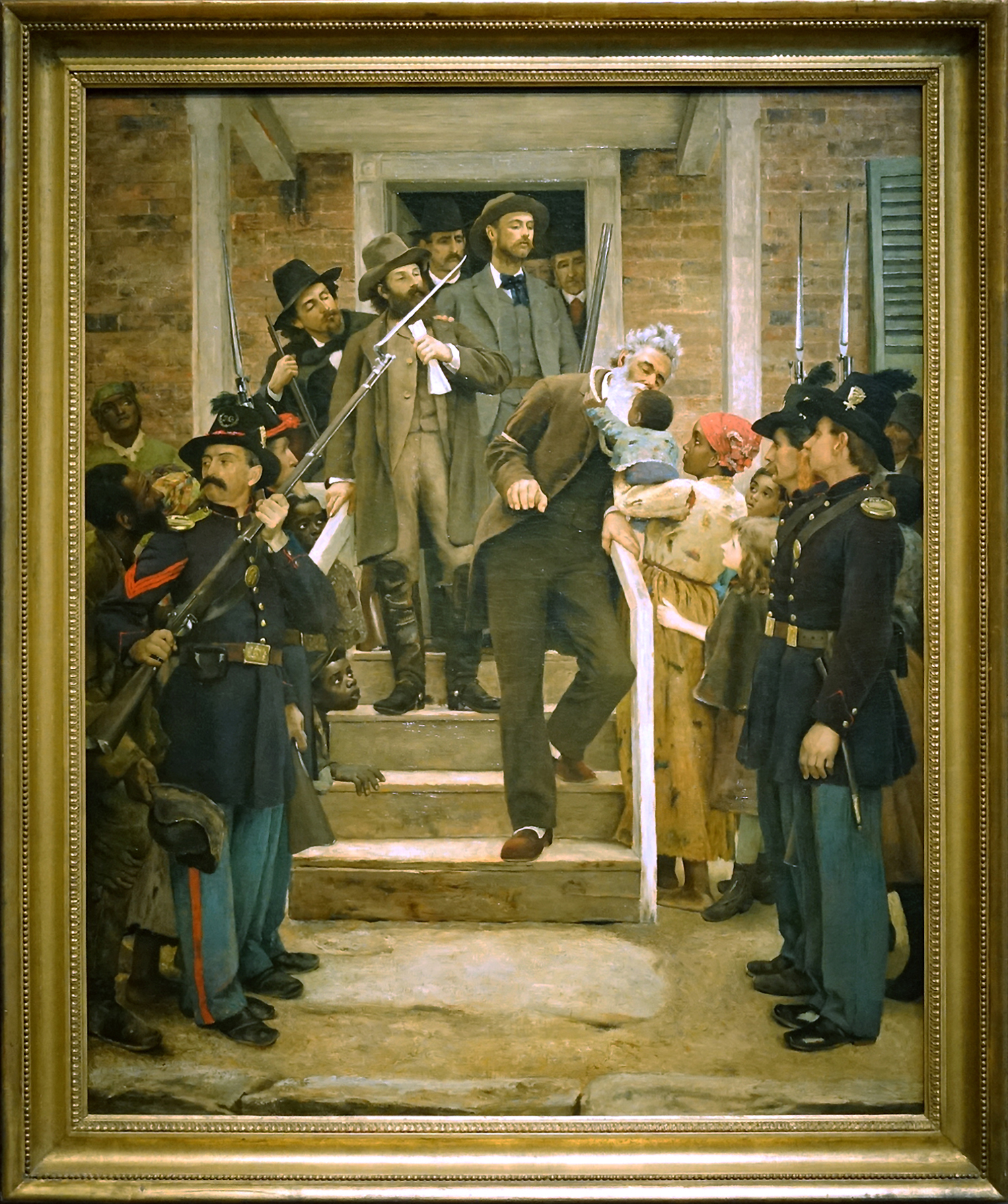

Thomas Hovenden, The Last Moments of John Brown, c. 1884, oil on canvas, 117.2 x 96.8 cm (de Young Museum, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; photo: Steven Zucker, CC NY-NC-SA 2.0)

“I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.” —John Brown, shortly before his execution, 1859

Who was John Brown?

Martyr. Murderer. Prophet. Madman. All of these words have been used to describe John Brown, the fiery abolitionist who led violent attacks against supporters of slavery in the years before the U.S. Civil War. A white man born into a deeply religious family of Connecticut abolitionists in 1800, Brown dedicated his life to a holy war against slavery. He scorned the tactic of moral suasion then in vogue among northern abolitionists, believing that only armed uprising could counter the evil of slavery. In 1859, he and a group of followers attempted to seize the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia) and distribute weapons to enslaved people so they could rise up against slaveholders. The plan failed and Brown was captured, tried, and executed amidst a media frenzy.

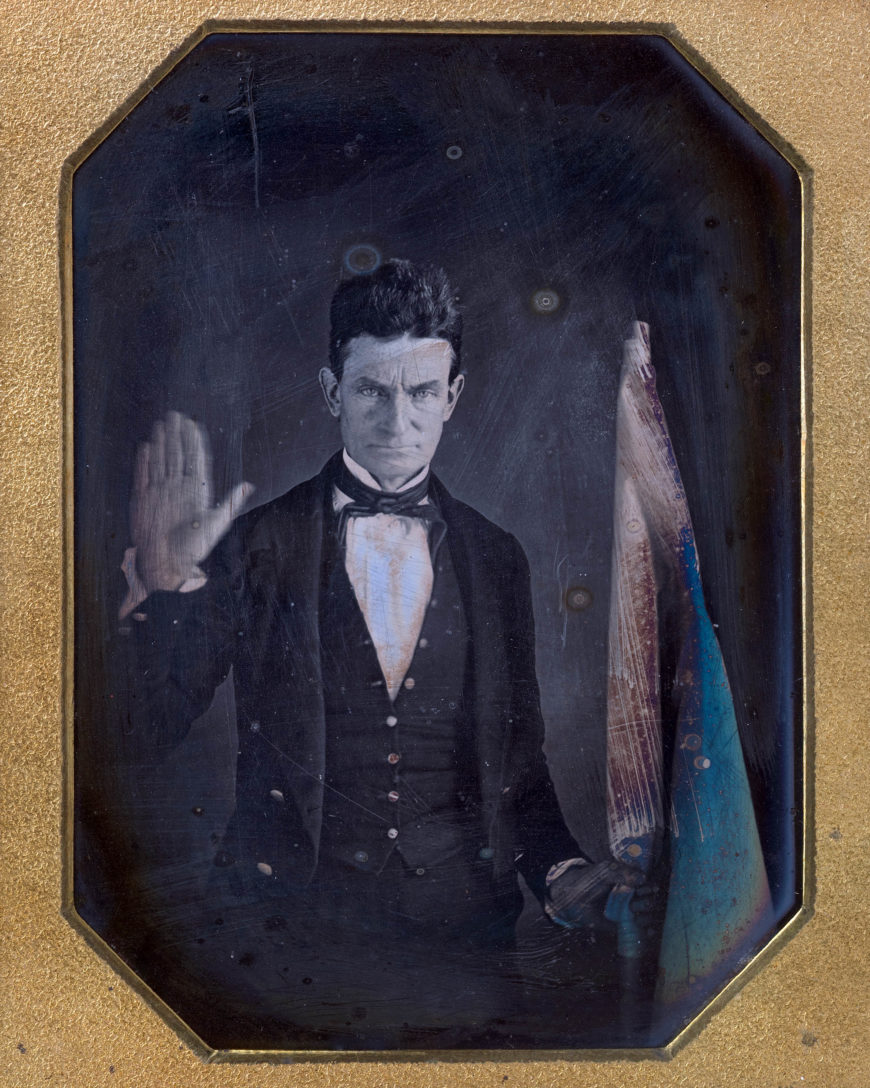

Daguerreotype depicting John Brown c. 1846. Brown was not, at this time, a well known figure, although he was active in abolitionist circles. Here, Brown poses with a determined look, holding up his left hand (photographic images such as this daguerreotype did not reverse images, so in order to appear that he was holding up his right hand in the finished image he had to hold up his left hand in reality) as though he is making an oath. In his right hand, he holds a flag believed to represent the “Subterranean Pass-Way,” a strategic initiative Brown envisioned that would transport enslaved people to freedom on a grand scale. The daguerreotypist, Augustus Washington, was an African American photographer with a studio in Hartford, Connecticut. Washington later emigrated to Liberia. Augustus Washington, John Brown, daguerreotype, 4 1/2 x 7 3/4 x 7/16 in. (11.4 x 19.7 x 1.1cm), Hartford, Connecticut (National Portrait Gallery)

From some perspectives, Brown could be considered a failure: his plan to bring about a massive uprising of enslaved people never came to fruition, and he was hanged for treason years before the Thirteenth Amendment outlawed slavery. But from other perspectives, Brown succeeded beyond his wildest dreams: his execution elevated him to the level of an abolitionist martyr, garnering sympathy for the cause he was willing to die for. His actions contributed to such paranoia among slaveholders about the future of slavery in the United States that slave states seceded when anti-slavery candidate Abraham Lincoln was elected president, putting in motion the events that ultimately would lead to slavery’s downfall.

John Steuart Curry, Tragic Prelude (detail), 1937–42, oil and egg tempera 11′ 6″ x 31 feet (Kansas statehouse, Topeka) This mural, in the Kansas State Capitol building, depicts John Brown as a fanatic, Moses-like figure, striding forward as clouds part in the sky (not unlike the parting of the Red Sea), in a composition reminiscent of Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People. He holds a rifle (the so-called “Beecher’s Bible” rifle sent to abolitionists fighting in the Kansas Territory) and an actual Bible featuring the Greek letters alpha and omega (a reference to Christ in the Book of Revelation, describing the Apocalypse). In the distance, covered wagons move right to left (westward). Behind Brown are figures holding the flag of the United States and the battle flag of the Confederacy. In the foreground, men wearing the uniforms of soldiers on each side of the Civil War lay dead at Brown’s feet. Beside his left knee we can make out soldiers violently assaulting a Black family. Curry depicts John Brown’s role in Bleeding Kansas as a “tragic prelude” to the Civil War, with tornadoes and prairie fires in the background representing the coming destruction. Curry did not revere Brown, describing him as a “bloodthirsty, god-fearing maniac.” [1]

The growing sectional divide of the 1850s

In the first half of the 19th century, the U.S. government worked to maintain the balance of political power between free and slave states by ensuring that their numbers remained equal. But, as the country expanded west to territories across the Mississippi River, with American settlers displacing the Indigenous inhabitants and forming new states, that balance began to falter. Several events in the 1850s contributed to a growing belief among anti-slavery activists that the “Slave Power,” as they called it, had gained control of the U.S. government: the introduction of a brutal Fugitive Slave Law (1850) required northern citizens to assist in the capture of enslaved people who had escaped; the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854) repealed an earlier ban on slavery in new territories north of the Missouri Compromise line; and the Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) ruled that Black Americans were not U.S. citizens.

Detail, John Steuart Curry, Tragic Prelude , 1937–42, oil and egg tempera 11′ 6″ x 31 feet (Kansas statehouse, Topeka)

John Brown first became a nationally known figure in 1856 through his actions in the Kansas Territory, three years before the raid on Harpers Ferry. Kansas was then the site of a territorial civil war known as Bleeding Kansas, the result of the Kansas-Nebraska Act’s provision allowing the residents of the territory to vote on whether to allow slavery. Pro- and anti-slavery settlers attempting to sway the vote flooded the region, and quickly came to blows. Among the ranks of “Free-Staters” were John Brown and five of his sons, who had come to Kansas to take up arms in defense of abolition.

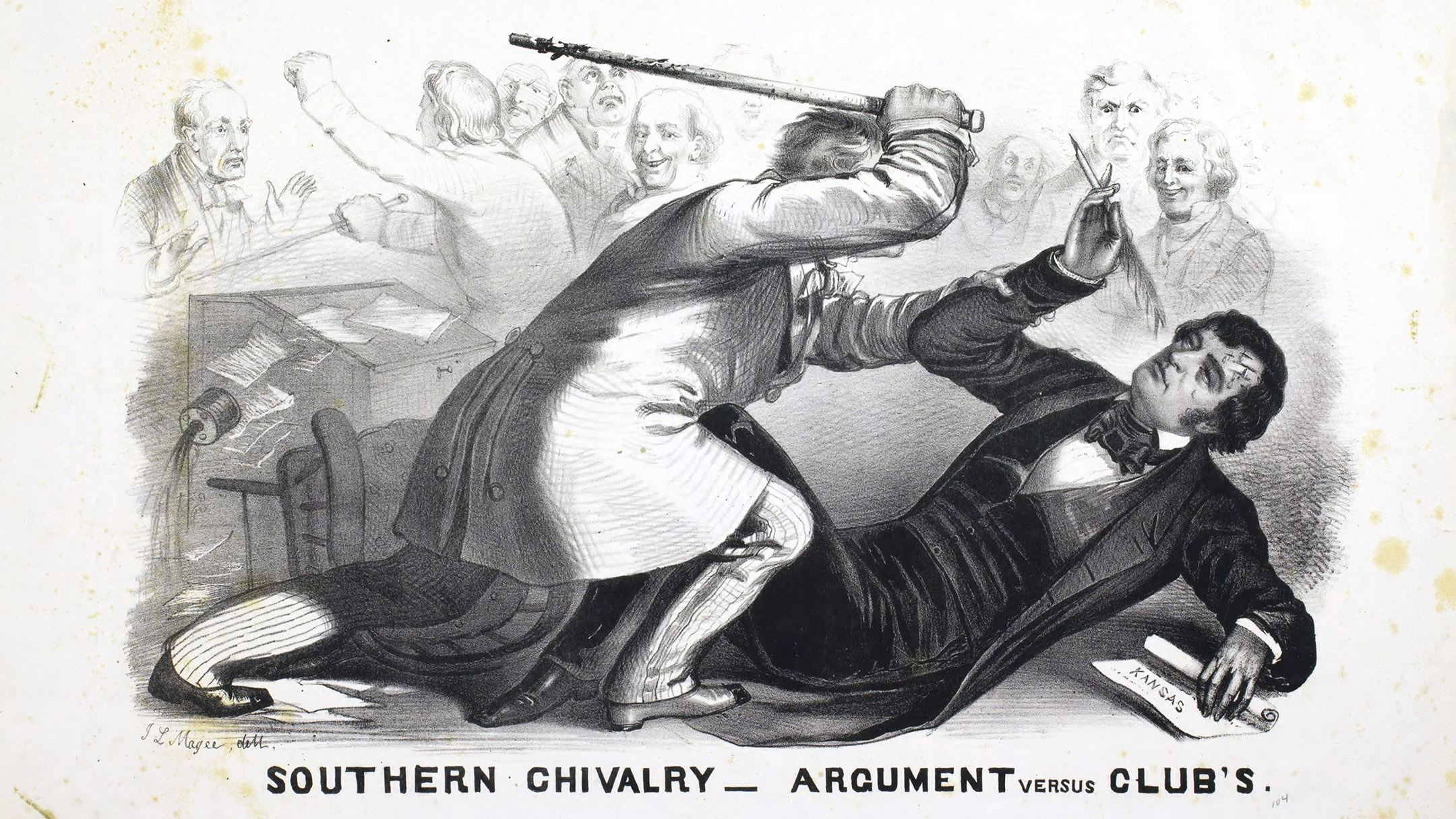

In May 1856, Brown led his sons and three other men in what came to be known as the Pottawatomie Massacre, a three-day rampage during which they murdered five members of the pro-slavery territorial district court in front of their families, hacking them to death with broadswords. Brown was enraged by two recent attacks on abolitionists by pro-slavery forces—the violent attack on the town of Lawrence, Kansas, then an abolitionist center, and the caning of abolitionist Charles Sumner on the Senate floor.The Pottawatomie Massacre escalated the violence in Kansas to a fever pitch, drawing federal troops to the territory. Brown and his allies engaged in battle with pro-slavery forces throughout the summer of 1856, becoming a ruthless leader whom southern slaveholders feared and northern abolitionists admired.

This political cartoon depicts the pro-slavery congressman Preston Brooks attacking the anti-slavery Senator Charles Sumner with a cane on the Senate floor. The title, “Southern Chivalry — argument versus club’s” ironically mocks this attack as “southern chivalry” since Sumner had criticized Brooks’s uncle as a lover of slavery in a recent speech (the “Crime Against Kansas” speech, which Sumner holds in his left hand). Here, Sumner is depicted bleeding, pen in hand, with a dignified expression while Brooks (whose face is blocked by his arm) raises a mangled cane to strike him again. John Brown was enraged by the attack on Sumner, which motivated his actions at Pottawatomie. John L. Magee, Southern chivalry – argument versus club’s, 1856, lithograph, 13.23 x 19 in. (The Library Company of Philadelphia)

The raid at Harpers Ferry

Although he was under indictment for the Pottawatomie murders, Brown managed to evade capture and make his way to the northeast, where he was received enthusiastically by abolitionists. Brown had long cherished the idea of leading a large-scale rebellion of enslaved people, like the Haitian Revolution or Nat Turner’s rebellion, and he spent several years traveling through New England and Canada, raising money, gathering weapons, and preparing for battle.

Brown eventually determined that he would lead a team of men to the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, distributing its weapons as he marched south to liberate enslaved Black people from plantations. Harpers Ferry was a strategic location not only because of its firearms cache but also for its position as a major rail and river junction (railroads and rivers were then the easiest ways to transport people and goods long distances). Brown believed that he would grow an ever larger army as the freed people joined him. He consulted with notable Black abolitionists about his plan, including Frederick Douglass—who counseled him against the action—and Harriet Tubman, who helped him recruit participants.

Map depicting U.S. state and territory boundaries in 1859, featuring the location of important events in the life of John Brown (underlying map © Google)

In October 1859, Brown and a group of twenty-one Black and white men captured the armory and took hostages, alerting the enslaved residents nearby of their plan. However, most of the enslaved people near Harpers Ferry were loath to trust an unknown white man, and to Brown’s surprise, the massive uprising that he had predicted failed to materialize. A train conductor raised the alarm, local militias pinned Brown and his men inside the armory, and by the following day U.S. Marines under the command of Robert E. Lee (the future Confederate general) arrived and demanded their surrender. Brown refused, and the Marines stormed the armory, wounded Brown, and took him and his seven remaining men (the others had died or escaped) prisoner.

Map depicting Harpers Ferry, a strategic location at the junction of railroads and rivers. Although Harpers Ferry was located in the slave state of Virginia, it was quite close to the free state of Pennsylvania (underlying map © Google)

The subsequent trial of Brown and his men for murder, inciting slave rebellion, and treason was widely reported in the national press. His speech upon conviction, in which he proclaimed that “if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I submit; so let it be done!” was printed in 50 newspapers, including on the front page of The New York Times.

John Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859. The story that he paused to kiss a Black infant on his way to the gallows was first circulated by Brown’s friend and supporter, journalist James Redpath, in a biography published just months after the execution to raise money for Brown’s widow and children.

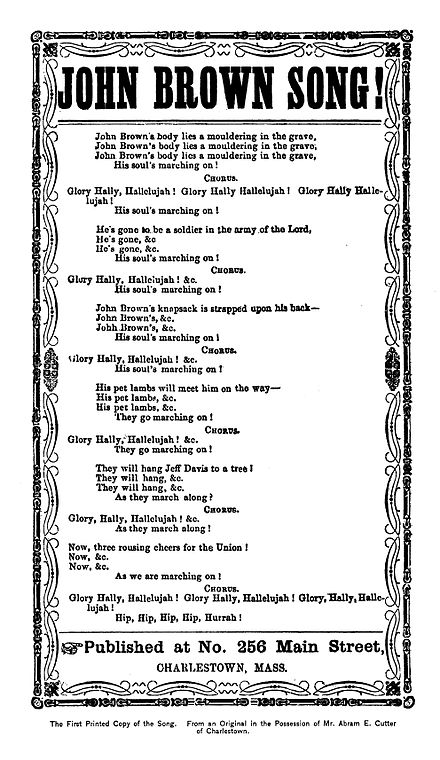

Songsheet featuring the lyrics of the “John Brown Song,” later called “John Brown’s Body.” Julia Ward Howe wrote new lyrics for the melody, producing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which became the anthem of U.S. forces during the Civil War. James E. Greenleaf, et. al., “John Brown Song!”, 1861.

John Brown in American memory

Although abolitionists praised Brown, many Republican politicians—including Abraham Lincoln—sought to distance themselves from him. [2] But once the Civil War was underway, Brown’s courageous fight against slavery took on new resonance. The song “John Brown’s Body,” a Civil War marching song, provided the inspiration for “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

Brown’s complex legacy has been viewed in different lights in the century and a half since his death. Frederick Douglass, who had to flee to England to escape possible retribution for his knowledge of Brown’s plans, later gave a speech praising him, saying that “If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he did at least begin the war that ended slavery.” [3] During the Jim Crow era, when mainstream American memory of the Civil War downplayed the importance of emancipation, many white historians portrayed Brown as a zealot and a madman, although Black intellectuals and artists, like W.E.B. DuBois and Jacob Lawrence, portrayed him sympathetically. Controversy over John Brown’s actions, and whether it’s acceptable to use violence to challenge social injustice, remains with us today.

Notes:

- Quoted in R. Blakeslee Gilpin, John Brown Still Lives!: America’s Long Reckoning with Violence, Equality, & Change (UNC Press, 2011), 154.

- Lincoln denied that Republicans supported Brown in his speech at Cooper Union in New York City on February 27, 1860: “You charge that we stir up insurrections among your slaves. We deny it; and what is your proof? Harpers Ferry! John Brown! John Brown was no Republican; and you have failed to implicate a single Republican in his Harper’s Ferry enterprise.”

- Frederick Douglass, “John Brown: An Address,” Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, May 30, 1881.

Additional resources:

Read about Augustus Washington’s daguerreotype of John Brown in Smithsonian Magazine

See Jacob Lawrence’s Legend of John Brown series at the Detroit Art Institute

Learn about John Brown’s “Holy War” from the American Experience on PBS

Hear the evolution of the John Brown song at Teachinghistory.org