In this portrait of Olympia and Laure, Manet is inventing what beauty could be for the modern world.

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 130 x 190 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] There’s a long tradition of the female nude represented in the most erotic, sensuous way, clothed by mythology or clothed by sheer beauty.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:15] It’s a tradition that goes back to the ancient Greeks and Romans — in sculptures, for example, of the goddess Venus modestly covering her body after her bath — and Manet, in this painting that we’re looking at here at the Musée d’Orsay, is clearly drawing on those traditions but doing something radically modern.

Dr. Zucker: [0:35] The immediate model for Manet was Titian’s “Venus of Urbino,” except he’s stripping away the academic technique of the representation of space, of the turn of the body, but he’s also stripping away that veil of mythology.

[0:48] By academic art, we’re talking about the kind of art that was sanctioned by the official Academy that was associated with the government of France.

Dr. Harris: [0:57] It didn’t challenge, particularly. It satisfied.

Dr. Zucker: [1:01] For one, because it had the stamp of the official state. These were the leading artists of the time, that were saying, “This art is of quality.” Of course, it had a ready market value. But at the same time, it was art that was formulaic, that was expected.

Dr. Harris: [1:15] Well, there was an idea that there was a definition of great art, and there was no point in looking for what was new or different, because great art was self-evident. Great art was based on the classical and the Renaissance.

[1:30] What someone like Manet is doing is challenging those very established ideas, ideas that seemed as natural as the sun coming up in the morning. She’s not a Venus. Her name is Olympia. She looks very much like a real woman in a real apartment in Paris.

Dr. Zucker: [1:49] How do you know she looks like a real woman as opposed to a Venus?

Dr. Harris: [1:53] Her features are not idealized. They’re not perfected. When we look at ancient Greek sculpture or Renaissance paintings of the nude, we have a woman who’s perfectly beautiful, and you can see her face is asymmetrical and her lips are a little bit too thin. She doesn’t have that perfection.

Dr. Zucker: [2:11] In addition, the representations of the academic artists always show Venus or other nudes in a coy way. This woman is looking directly at us. She is sentient. She is thinking. She’s confronting us, even as we look at her.

Dr. Harris: [2:27] There was a real problem for the viewers of this painting. There’s no way to look at her and pretend that it was about beauty. One was confronted by her sexuality.

Dr. Zucker: [2:38] This woman was recognized as a courtesan, that is, as a kind of prostitute.

Dr. Harris: [2:42] The name Olympia was common for prostitutes at that time in Paris.

Dr. Zucker: [2:47] What we’re seeing here is Olympia’s servant handing her flowers that presumably have just come from one of her customers. Look at the way that Olympia’s looking out towards us. We must have, as the customer, walked into the room, and startled the cat at the foot of the bed as well as the two figures.

Dr. Harris: [3:05] When we use the word prostitute, we think of a figure of much lower class. Here, we have a woman who’s a higher-class prostitute.

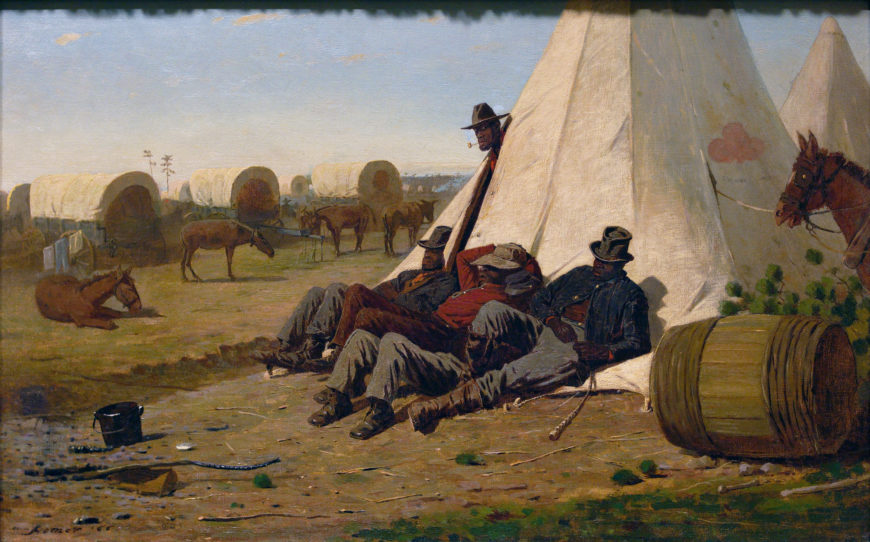

Dr. Zucker: [3:14] Important new scholarship has helped us to better understand one of the two primary figures in this painting.

Dr. Harris: [3:20] New scholarship by Denise Murrell helps us see that this is part of his attempt to capture modern life in Paris. And modern life in Paris was decidedly diverse.

Dr. Zucker: [3:31] Murrell’s research opens up this painting. It tells us that this is a painting that is not just a reprise of the Venus in Titian’s “Venus of Urbino.” It expresses modernity in its inclusion of a Black woman, a woman who had posed for him for a gorgeous portrait, and even before that, on the side of a painting of children in the Tuileries Gardens.

Dr. Harris: [3:52] There was a small Black community in the northern part of Paris. After 1848, when territorial slavery was finally outlawed in France, that population grew. Laure lived only 20 minutes away from Manet, and close to many of the other painters and prominent artists of the time.

Dr. Zucker: [4:13] Look at the way that Manet paints Laure in relationship to Olympia. Olympia is static, almost like a sculpture, whereas Laure seems to be momentary, seems to be a part of the modern world, seems to be in motion.

Dr. Harris: [4:26] We do not know Laure’s last name. We think that she was likely from the Caribbean or from Africa, but Laure is mostly lost to history.

Dr. Zucker: [4:35] Importantly, this scholarship notes that Manet has dressed her in modern clothing, but with a reference still to the Caribbean. That can be seen in her head wrap.

Dr. Harris: [4:45] Most images at this time of Black figures were either exoticized, romanticized, or they’re ethnographic. In other words, they are an attempt to capture a certain type. But Manet seems more interested in presenting Laure as a modern Black woman in Paris.

Dr. Zucker: [5:04] The reaction of the press was pretty vicious.

Dr. Harris: [5:07] The press said Olympia looked like a cadaver. Manet outlined her in black, and hardly modeled her flesh.

Dr. Zucker: [5:14] Some of the caricatures that were made of this emphasized the shadow on her hands and feet. Some of the press actually spoke of her hands being filthy. It’s interesting that those are the only areas where there’s significant modeling.

Dr. Harris: [5:27] Where one would expect to see modeling on the female nude would be in the abdomen, around the breasts. Here Manet’s kept that really flat. The areas that we do see shadow are unexpected, so the press interpreted her hand as drawing attention to her sexuality, even though nudes for centuries had shown women with their hand placed across their genitals.

Dr. Zucker: [5:50] You mentioned the kind of flatness of her body. Some art historians even said, she’s a bit of a paper cutout. Manet, in so much of his work, really does reject the clear articulation of represented space and confronts the viewer with the complexity of painting on a two-dimensional surface.

[6:09] An area where you can really see that are, for instance, in the way the toes peek out from under her slipper. There is this awkwardness that reminds us that all of this is illusion, and that in fact, there is just this two-dimensionality of this canvas.

Dr. Harris: [6:22] Manet is saying, “I’m not going to pretend that my painting isn’t paint. I’m not going to present you with this perfect illusion, the way that academic artists are doing, where you don’t even see a brush stroke.” He’s insisting on unmasking that illusion, and then he’s insisting on unmasking the illusion of our own interests. In looking at these images, he’s reminding us that our interest here is a sexual one.

Dr. Zucker: [6:52] In so many traditional representations of the nude, because the figure is not looking out at us, we can comfortably look at her. Here, we’re confronted by her gaze and by her thinking. There is a much more problematic experience here.

Dr. Harris: [7:07] That’s in the fact that she’s a real woman, she’s contemporary, and the way she picks her head up, the way she looks out at us, the angularity of her body. People at the time, in 1865, recognized it.

Dr. Zucker: [7:19] This is a painting that is about art making and about the conventions that exist in art and making us, the viewer, aware of those conventions even as we look at this painting.

Dr. Harris: [7:30] Manet is saying, “Let’s be honest about the materials. Let’s be honest about the subject and our own motives and desires.” The great poet and art critic, Charles Baudelaire, called on artists to paint the beauty of modern life. I think Manet is taking up that call.

Dr. Zucker: [7:47] Manet is inventing what beauty could be for the modern world.

[7:52] [music]

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 130 x 190 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

“They are raining insults upon me!”

Manet’s complaint—”They are raining insults upon me!” to his friend Charles Baudelaire pointed to the overwhelming negative response his painting Olympia received from critics in 1865. Baudelaire (an art critic and poet) had advocated for an art that could capture the “gait, glance, and gesture” of modern life, and, although Manet’s painting had perhaps done just that, its debut at the salon only served to bewilder and scandalize the Parisian public.

Cat (detail), Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 130 x 190 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Mocking the classical past

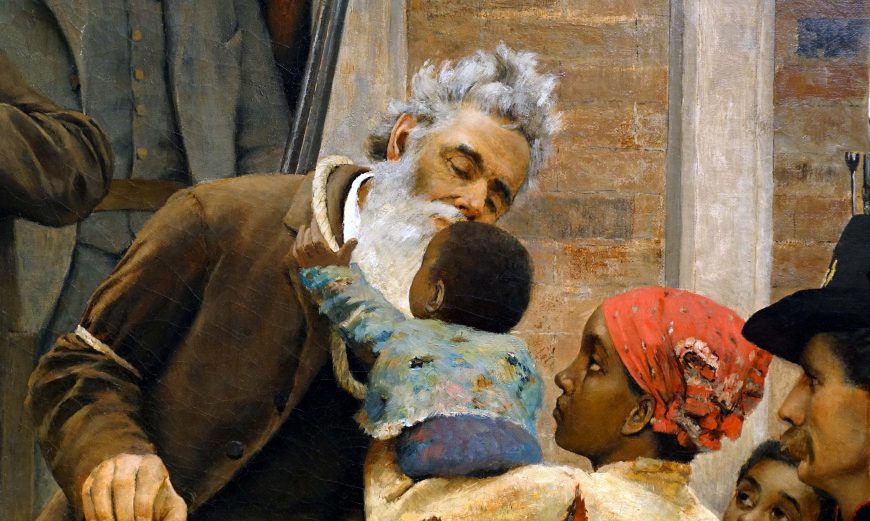

Olympia features a nude woman reclining upon a chaise lounge, with a small black cat at her feet (image above), and a Black female servant behind her brandishing a bouquet of flowers (image below). It struck viewers—who flocked to see the painting—as a great insult to the academic tradition. And of course it was. One could say that the artist had thrown down a gauntlet. The subject was modern—maybe too modern, since it failed to properly elevate the woman’s nakedness to the lofty ideals of nudity found in art of antiquity —she was no goddess or mythological figure. As the art historian Eunice Lipton described it, Manet had “robbed,” the art historical genre of nudes of “their mythic scaffolding…”[1] Nineteenth-century French salon painting (sometimes also called academic painting—the art advocated by the Royal Academy) was supposed to perpetually return to the classical past to retrieve and reinvent its forms and ideals, making them relevant for the present moment. In using a contemporary subject (and not Venus), Manet mocked that tradition and, moreover, dared to suggest that the classical past held no relevance for the modern industrial present.

Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538, oil on canvas, 119.20 x 165.50 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As if to underscore his rejection of the past, Manet used as his source a well-known painting in the collection of the Galleria degli Uffizi—Venus of Urbino, a 1538 painting by the Venetian Renaissance artist Titian (image above)—and he then stripped it of meaning. To an eye trained in the classical style, Olympia was clearly no respectful homage to Titian’s masterpiece; the artist offered instead an impoverished copy. In place of the seamlessly contoured voluptuous figure of Venus, set within a richly atmospheric and imaginary world, Olympia was flatly painted, poorly contoured, lacked depth, and seemed to inhabit the seamy, contemporary world of Parisian prostitution.

Why, critics asked, was the figure so flat and washed out, the background so dark? Why had the artist abandoned the centuries-old practice of leading the eye towards an imagined vanishing point that would establish the fiction of a believable space for the figures to inhabit? For Manet’s artistic contemporaries, however, the loose, fluid brushwork and the seeming rapidity of execution were much more than a hoax. In one stroke, the artist had dissolved classical illusionism and re-invented painting as something that spoke to its own condition of being a painted representation.

Left: Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538, oil on canvas, 119.20 x 165.50 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 130 x 190 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The birth of modernist painting

It was for this reason Manet is often referred to as the father of Impressionism. The Impressionists, who formed as a group around 1871, took on the mantle of Manet’s rebel status (going so far as to arrange their own exhibitions instead of submitting to the Salon juries), and they pushed his expressive brushwork to the point where everything dissolved into the shimmering movement of light and formlessness. The 20th century art critic Clement Greenberg would later declare Manet’s paintings to be the first truly modernist works because of the “frankness with which they declared the flat surfaces on which they were painted.”[2]

Gustave Courbet, A Burial at Ornans, begun late summer 1849, completed 1850, 124 x 260 inches, oil on canvas (Musée d’Orsay, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Manet had an immediate predecessor in the Realist paintings of Gustave Courbet, who had himself scandalized the Salons during the 1840s and ‘50s with roughly worked images of the rural French countryside and its inhabitants. In rejecting a tightly controlled application of paint and seamless illusionism—what the Impressionists called the “licked surfaces” of the paintings of the French Academy—Manet also drew inspiration from Spanish artists Velasquez and Goya, as well as 17th century Dutch painters like Frans Hals, whose loosely executed portraits seem as equally frank about the medium as Manet’s some 200 years later. But Manet’s modernity is not just a function of how he painted, but also what he painted. His paintings were pictures of modernity, of the often-marginalized figures that existed on the outskirts of bourgeois normalcy. Many viewers believed the woman at the center of Olympia to be an actual prostitute, coldly staring at them while receiving a gift of flowers from an assumed client, who hovers just out of sight (Manet here puns on the way French prostitutes often borrowed names of classical goddesses). The model for the painting was actually a salon painter in her own right, a certain Victorine Meurent, who appears again in Manet’s The Railway (1873) and Auguste Renoir’s Moulin de la Galette (1876).

Face (detail), Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 130 x 190 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Disturbingly familiar but startlingly new

Manet had created an artistic revolution: a contemporary subject depicted in a modern manner. It is hard from a present-day perspective to see what all the fuss was about. Nevertheless, the painting elicited much unease and it is important to remember—in the absence of the profusion of media imagery that exists today—that painting and sculpture in nineteenth-century France served to consolidate identity on both a national and individual level. And here is where the Olympia’s subversive role resides. Manet chose not to mollify anxiety about this new modern world of which Paris had become a symbol. For those anxious about class status (many had recently moved to Paris from the countryside), the naked woman in Olympia coldly stared back at the new urban bourgeoisie looking to art to solidify their own sense of identity. Aside from the reference to prostitution—itself a dangerous sign of the emerging margins in the modern city—the painting’s inclusion of a Black woman tapped into the French colonialist mindset while providing a stark contrast for the whiteness of Olympia. The Black woman also served as a powerful emblem of “primitive” sexuality, one of many fictions that aimed to justify colonial views of non-Western societies.

Servant (detail), Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas, 130 x 190 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

If Manet rejected an established approach to painting that valued the timeless and eternal, Olympia served to further embody, for his scandalized viewers, a sense of the modern world as one brimming with uncertainty and newness. Olympia occupies a pivotal moment in art history. Situated on the threshold of the shift from the classical tradition to an industrialized modernity, it is a perfect metaphor of an irretrievably disappearing past and an as yet unknowable future.