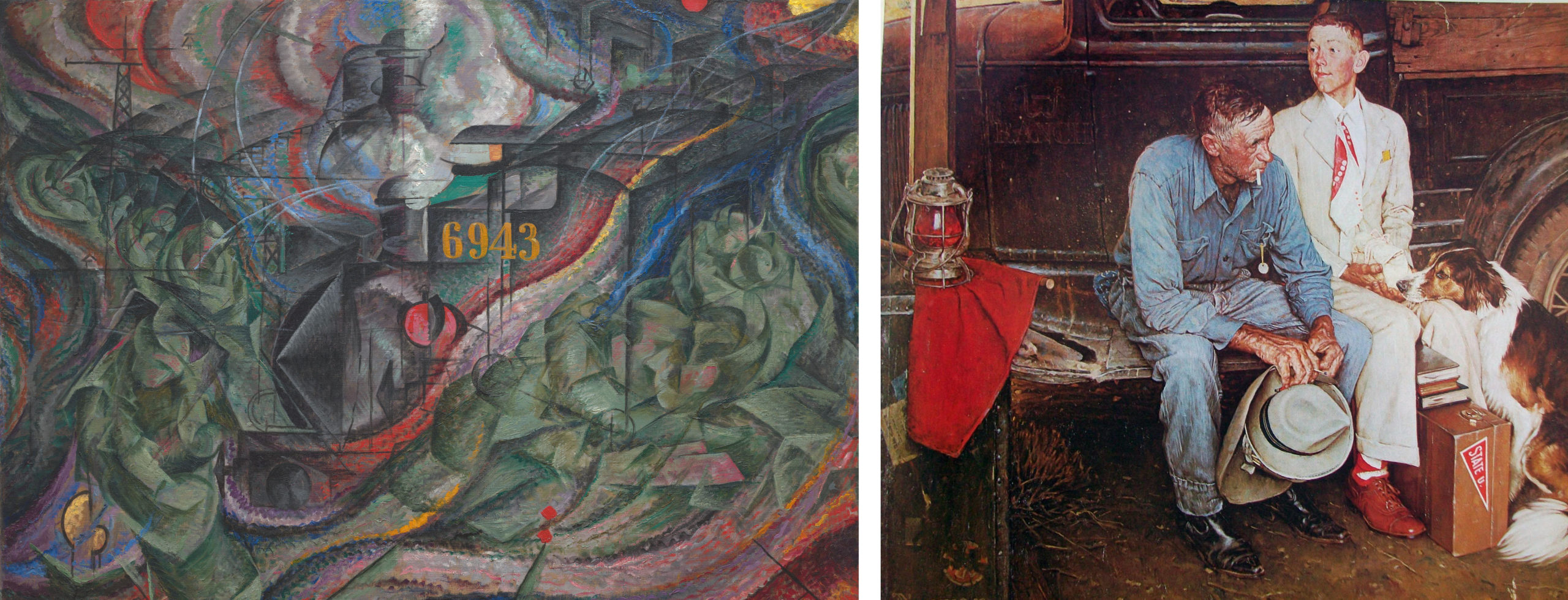

Left: Umberto Boccioni, States of Mind: The Farewells, 1911, oil on canvas, 70.5 x 96.2 cm (MoMA); Right: Norman Rockwell, Breaking Home Ties, 1954, oil on canvas, 112 x 112 cm (private collection)

If asked, most people would probably say that modern art is not true to reality. Indeed, modern art is practically defined by its bizarre distortions of reality; this is one reason why Norman Rockwell, whose work is more recent than Umberto Boccioni’s, is not considered a modern artist. But looking like reality — what art historians call “naturalism” — is only one way of being true to reality. As we shall see, the attempt to create art that was more true to reality than traditional naturalism was the motivation for some of the most radical modern art, even including Boccioni’s States of Mind: The Farewells.

Impressionism and optical realism

When the Impressionist style first appeared on the art scene of the 1870s, many hostile viewers dismissed it as art by “lunatics” whose color perception was questionable and who did not have the technical skills to properly finish their paintings. Some critics claimed, however, that Impressionist paintings were more accurate than traditional naturalistic representations. Their argument was that the Impressionists represented their perception of objects rather than the objects themselves, and that the colors we perceive are often not identical to an object’s actual or “local” color.

Left: Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral (The Portal and the Tour d’Albane in full Sunlight) also called Harmony in Blue and Gold, painted 1893, dated 1894, oil on canvas, 107 x 73 cm (Musée d’Orsay); Right: Rouen Cathedral, Portal, Morning sun, 1893, oil on canvas, 92.2 x 63.0 (Musée d’Orsay)

In the 1890s, Monet created dozens of paintings of Rouen Cathedral at different times of day and in different weather. At dawn, the cathedral was tinged with blue light; in the late-afternoon, it was radiant with oranges and yellows; while on cloudy days it was a duller grayish tan. By recording how the appearances of objects are affected by different lighting conditions, the Impressionists argued that their paintings were more accurate representations of the way we see the world. What appears at first sight to be a radically unrealistic style is in fact more true to the way things actually look.

Top: Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m (Musée du Louvre); Bottom: Edgar Degas, The Race Track: Amateur Jockeys near a Carriage, between 1876 and 1887, oil on canvas, 66 × 81 cm (Musée d’Orsay)

Discarding artificial conventions

The Impressionists recognized that much traditional art was accepted as true to reality only because it was familiar, not because it was accurate. For example, methods of composition taught in Academies tended to emphasize a central focus, equal balance on both sides, and a clear depiction of spatial recession, as in David’s Oath of the Horatii. Such compositions are, in fact, very artificially staged. When we move through the world, we are more likely to encounter scenes like the one represented in Degas’s The Race Track: awkwardly unbalanced, abruptly cropped, and spatially ambiguous. Critics who supported the Impressionists argued that artists like Degas were correcting artificial conventions and making art more true to reality.

Although the Impressionist style was new, this form of argument was not. In the sixteenth century artists and critics tried to draw a distinction between a true naturalism and a false naturalism (often derogatorily called “Mannerism“). False naturalism involved copying the work of other artists, and thus understanding nature only at second hand. The solution, some felt, was to discard the conventions of art and return to a more careful study of the original source, nature itself, just as the Impressionists did.

Is naturalism true to nature?

Impressionist artists sought greater truth to nature through more careful observation, but there is a sense in which our eyes inevitably distort the objects they perceive. Three ways they do so are embodied in the artistic techniques of linear perspective, diminution, and foreshortening.

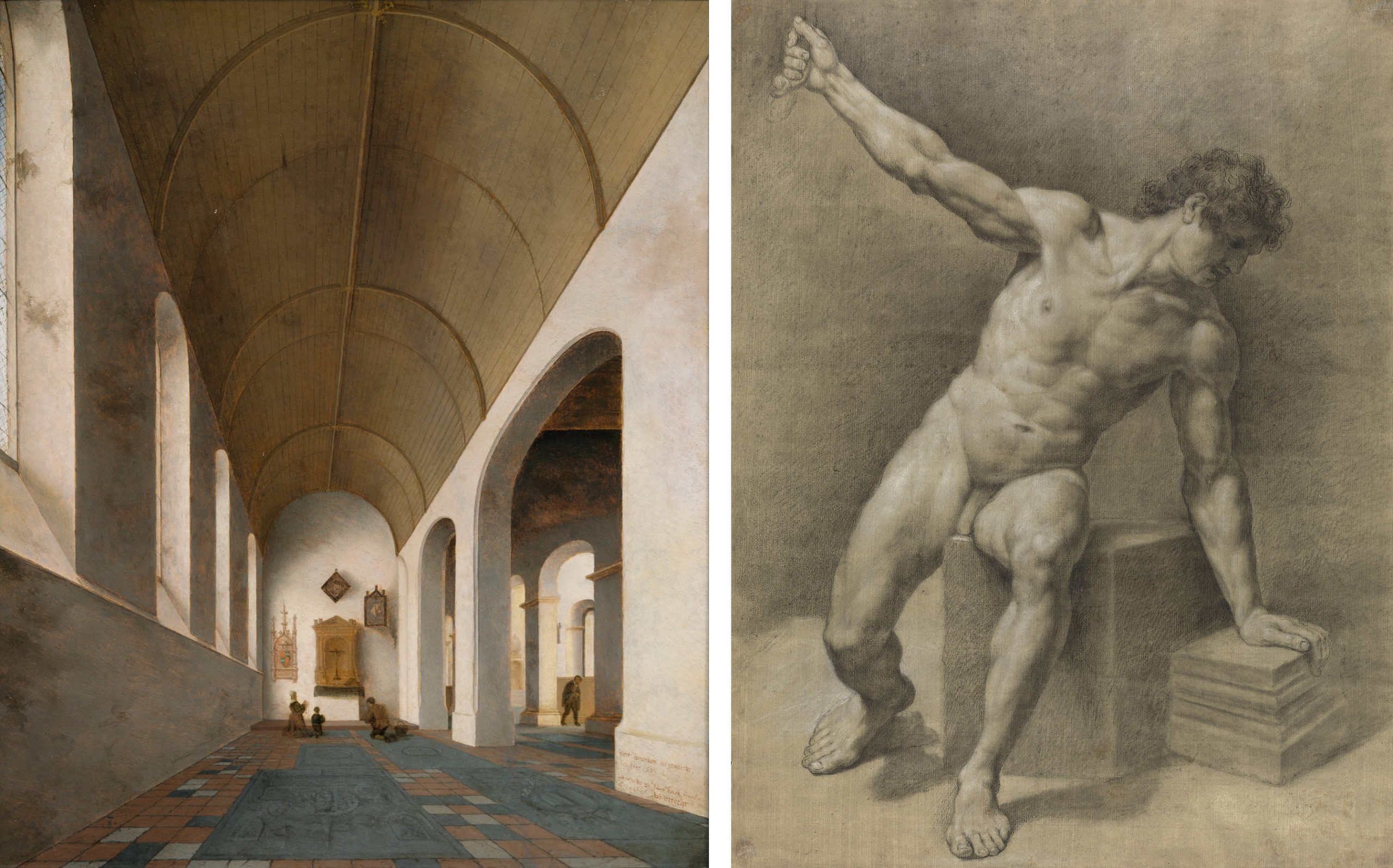

Left: Pieter Saenredam, St Antoniuskapel in St Janskerk, Utrecht, 1645, oil on panel, 41.7 x 23 cm, (Centraal Museum, Utrecht); Right: Anton von Maron, Academic nude study, late 18th or early 19th century, black and white chalk on paper, 52.7 x 39.4 cm (private collection)

In linear perspective, what are actually parallel lines in real life (such as railroad tracks or the edges of floor tiles) converge in the representation. This effect, seen above in the Saenredam painting of a church interior, is integral to what is popularly considered a realistic style, but it is obviously not true to reality. Each of the tiles on the floor is in fact square. Similarly, with diminution, objects appear to get smaller the farther away they are, but this is just an optical trick; each of those windows is in reality the same size.

Foreshortening occurs when we view an object from an angle at which it recedes away from us, so that the object appears to be contracted, shorter than its actual length. In the Academic figure study above on the right, the two thighs appear to be of different lengths and shapes simply because one is viewed parallel to the picture plane while the other is receding sharply away from it. In actual reality, of course, both thighs are very similar (mirror images) in length and shape.

Correcting for perceptual distortion

The style we colloquially call “realistic” is not literally true to reality, then. It is only a record of our perception of reality, from one angle, at one distance, at one moment in time, and in one kind of light, and all of these factors can distort the object. Some Modern art movements sought a representational system that would be more accurate to the true shapes of objects, rather than representing them deformed by perception.

Jean Metzinger, Le Goûter, 1911, oil on cardboard, 29 7/8 x 27 5/8 inches (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Cubist paintings seem at first sight to be even more bizarrely distorted and unrealistic than Impressionist paintings. In the Salon Cubist Jean Metzinger’s Le Goûter, objects appear to be twisted and broken up, but this is done in order to correct the distortions of perspective and foreshortening. Metzinger shows things from multiple perspectives so we can better understand their true shapes. The left side of the tea cup on the table is seen from the side at eye level, but from that angle you wouldn’t be able to tell that the cup has a round opening, so the right side is seen from above to complete our understanding of the round lip and concave shape of the cup. Similarly, one of the woman’s eyes is viewed in profile, while the other is seen facing us, and her left shoulder is seen from above, while the right is more straight on. Cubism doesn’t “distort” objects; it shows them from multiple angles in order to give us more information about their true shapes than would be visible in traditional naturalistic representation.

Modernism and science

Another way of justifying the apparent distortions of modern art came in the form of appeals to science. Modern science provided a stream of new images that sparked artists’ imaginations, as well as new theories that radically altered people’s understanding of reality.

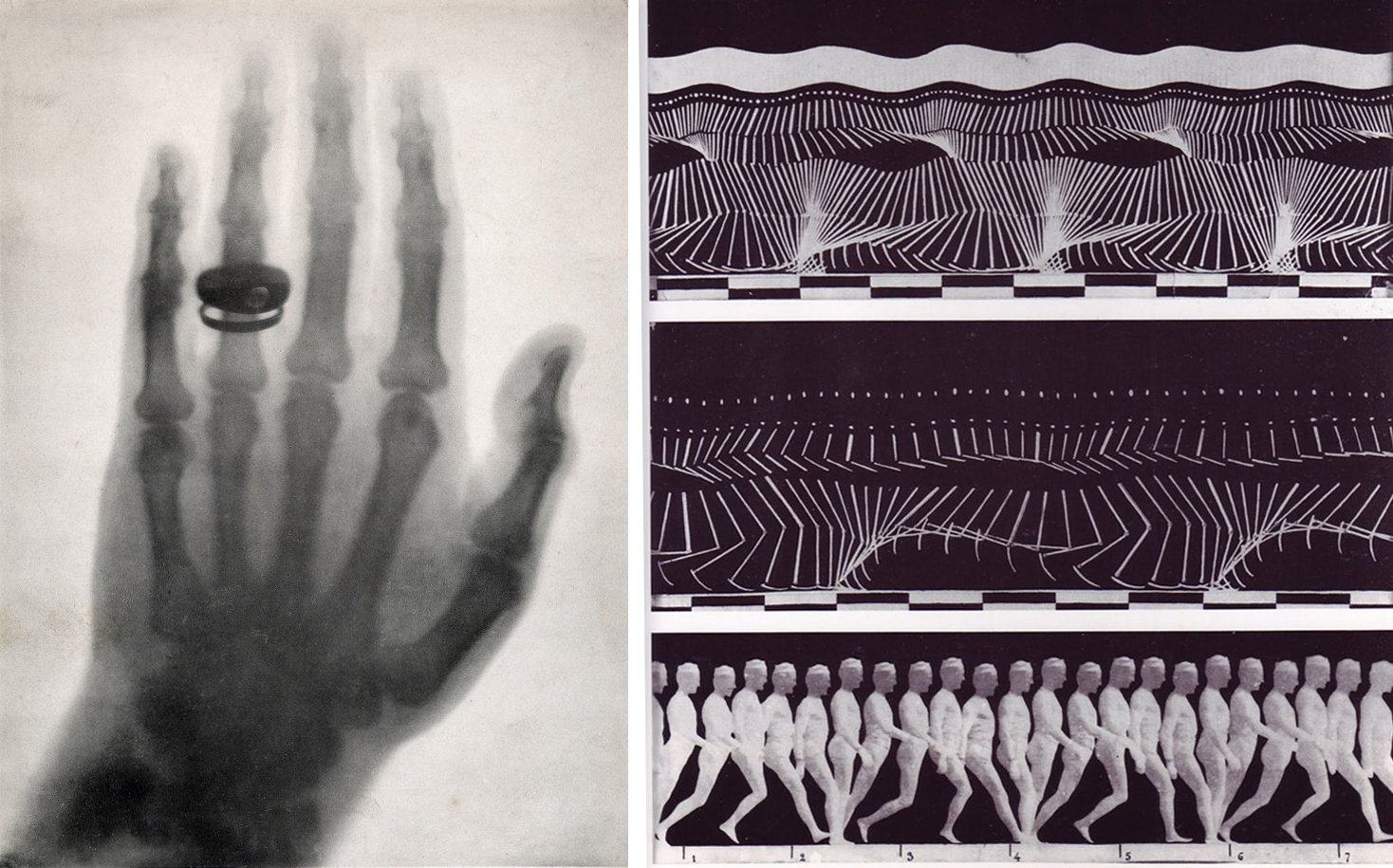

Left: Wilhelm Röntgen, X-ray photograph of the hand of Albert von Kölliker, from Eine Neue Art von Strahlen (Würzburg, 1895); Right: Étienne-Jules Marey, photographs showing human locomotion, c. 1895

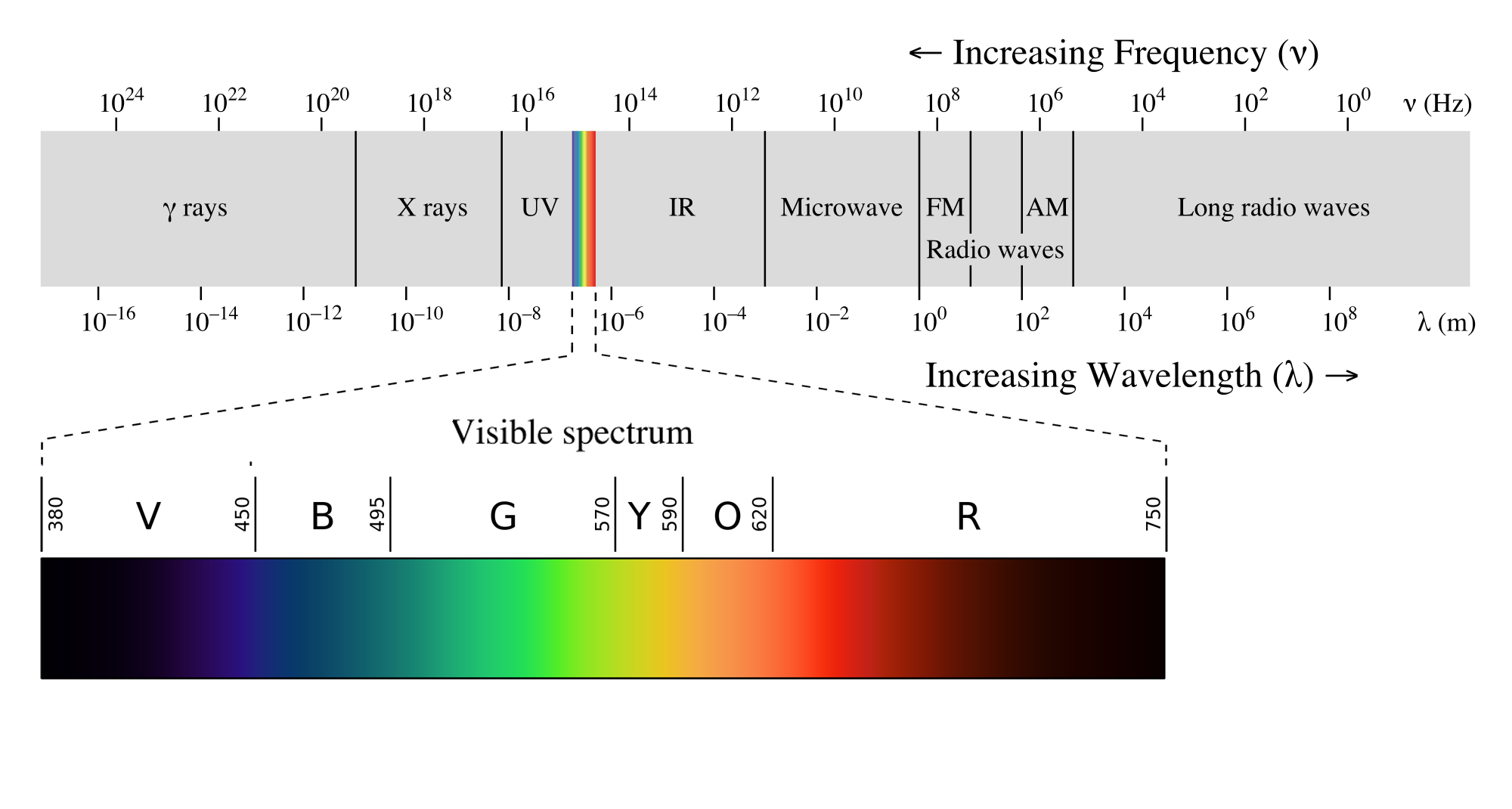

Beginning in the seventeenth century, new technologies based on the use of optical lenses provided evidence of microscopic and macroscopic worlds hitherto unsuspected. The discovery of wavelengths beyond the visible spectrum, including infrared and ultraviolet light as well as x-rays, gamma rays, and radio waves, made it clear that the human senses are very limited instruments for understanding the objective world. The visual culture of modern science provided new ways of representing and understanding reality. Stop-motion photography made rapid actions visible for study, and x-ray photography allowed peeks into the interior of solid forms, resulting in visions of reality beyond traditional naturalism.

Diagram of the electromagnetic spectrum (image: Philip Ronan, Gringer, CC BY-SA 3.0)

One work that attempted to represent this new super-sensory reality was Italian Futurist Umberto Boccioni’s States of Mind: The Farewells (1911). The only clearly legible feature in the painting is the number 6943 stenciled on what we gradually discern is the engine of a dark-gray train engine spewing steam in a station. The train is represented, Cubist-fashion, from multiple perspectives. The nose cone is in profile, while the body of the train recedes in a zig-zag toward the upper right then upper center of the canvas. In front of the train in green are a series of a couples saying goodbye (their two heads and embracing arms are clearest in the lower left) — or perhaps they are one couple, viewed multiple times in the manner of stop-action photography in order to show motion through time.

Two truss structures on the left suggest the radio towers that were constructed across Europe in the first decades of the twentieth century after the Italian Guglielmo Marconi harnessed radio waves for wireless communication. Correspondingly, the remainder of the composition is permeated with wave-forms in bright colors to suggest their high energy. Many forms of electromagnetic energy such as radio waves are invisible to the eye, but nonetheless permeate the world. Altogether, the work makes visible the new understanding of nature achieved by modern physics and presents a glimpse of reality beyond the limitations of the human senses.

Modernism and spiritualism

Modern artists’ quest for truth to realities beyond human perception was also influenced by the explicitly non-scientific approaches of spiritualism. Although spiritual visions and discoveries are often seen as subjective, many modern artists saw them as revealing objective truths. They claimed their depictions of these discoveries were glimpses of a higher reality than that available to the human senses.

Left: Hilma af Klint, Group X, No. 1, Altarpiece (Altarbild), 1915. Oil and metal leaf on canvas, 93 1/2 x 70 11/16 inches (237.5 x 179.5 cm); Right: Piet Mondrian, Composition, 1929, oil on canvas, 45.1 x 45.3 cm (Guggenheim Museum)

The Swedish artist Hilma af Klint painted a series of works called The Paintings for the Temple between 1905 and 1915 based in part on mystical visions she received from a spiritual guide. Around the same time, the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian undertook a close study of nature to eventually discover what he felt were the basic “building blocks” of all natural and artistic form: the primary colors red, yellow, and blue; the primary values black and white, and horizontal and vertical lines. Although both of these artists produced some artworks that are entirely non-representational in the sense that they do not look like nature, both argued that their spiritual quest revealed a higher reality than that available to the senses.

These artists all remind us that what is popularly considered ”realistic” in art is in fact only based on sense perceptions, which are inevitably partial, and which in many cases distort reality. By observing nature more closely, discarding artificial conventions, correcting for perceptual distortions, absorbing new scientific theories, and engaging in spiritual investigations, many modern artists rejected traditional naturalism in order to seek higher truths.