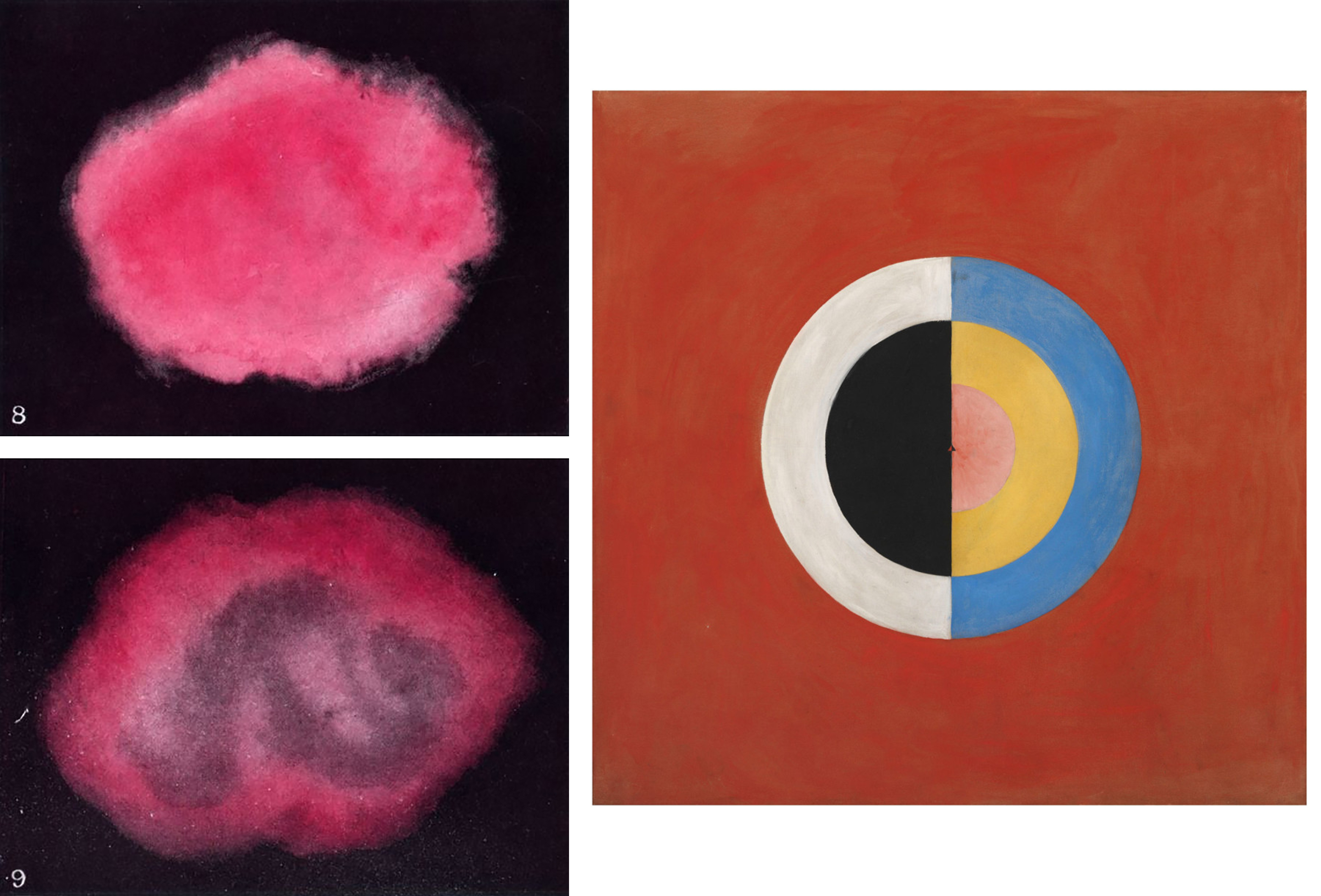

Left: Figures 8 and 9 from Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater, Thought Forms, 1905 (London: The Theosophical Publishing House LTD); right: Hilma af Klint, Group IX/SUW, No. 17. The Swan, 1915, oil on canvas, 150.5 × 151 cm (Moderna Museet / Stockholm)

On the left, two amorphous pinkish clouds float against a black field; and on the right, a nested set of hard-edged, bisected disks converge toward a tiny equilateral triangle. These images look like they belong in the milieu of mid-twentieth century Abstract Expressionism, but they were actually produced almost half a century earlier by two remarkable women, Annie Besant and Hilma af Klint. They provide the first hints of the way in which abstract art was underwritten by a very surprising

source: an occult spiritualist movement called Theosophy. Many early abstractionists, including Vassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Kasimir Malevich, and František Kupka, as well as Hilma af Klint, cited Theosophy as a direct source for their ideas and works.

The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875, was probably the most influential spiritualist organization of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century. Theosophy was a highly eclectic mixture of religious, philosophical, and occultist ideas. One of the founders, Madame Blavatsky, wrote books that mix elements of Hinduism and Buddhism with Ancient Greek philosophy and modern science.

The Society had no formal dogma or established rituals, and had multiple, sometimes competing, centers and leaders around the world. Its members generally believed that there were truths beyond the reach of science, and that throughout history certain enlightened individuals or Mahatmas (including Abraham, Jesus, Buddha, and Confucius) used spiritual discipline to grasp these truths and obtain supernatural powers.

Symbolism

The connection between Theosophy and formally-innovative modern art begins in the late-nineteenth century, when some artists and writers reacted strongly against the materialism of an age dominated by science and industrialization. In an 1892 essay, the art critic Albert Aurier decried the futility of scientific reasoning in the face of the deeper mysteries of life:

The nineteenth century, after having proclaimed for eighty years, in its infantile enthusiasm, the omnipotence of observation and of scientific deduction, after having affirmed that no mystery could survive its lenses and its scalpels, seems finally to realize the vanity of its efforts, the puerility of its boasts.Albert Aurier, “Les peintres symbolistes,” in Textes critiques, 1889-1892 (Paris: Ecole nationale supérieur des Beaux-Arts, 1995), pp. 29-30 (authors’ translation)

Aurier saw hope for the future in a new art movement called Symbolism, led by Paul Gauguin. Gauguin’s work demonstrates his rejection of science and modernity most obviously in its turn away from the modern, urban subjects preferred by the Impressionists in favor of rural and religious subject-matter. His Vision after the Sermon, which Aurier described as the first masterpiece of the new movement, shows a group of Breton peasant women leaving church and having a collective vision of the Biblical patriarch Jacob wrestling an angel (Genesis 32:22-32).

Paul Gauguin, Vision after the Sermon (or Jacob Wrestling with the Angel), 1888, oil on canvas, 72.20 x 91.00 cm (National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh)

Equally important is the work’s style, which rejects what had been a constant in Western art since the Renaissance: a basis in naturalism. Anatomy in Gauguin’s work is rendered with the crude simplicity of a medieval woodcut. There is very little chiaroscuro to indicate volume, and the ground is painted a virtually unmodulated red, defying expectations of both spatial recession and naturalistic color choice.

Paul Sérusier, Portrait of Paul Ranson in Nabi costume, 1890, oil on canvas, 51 x 46.5 cm (Musée d’Orsay)

Following Gauguin, a number of Symbolist artists affirmed this linkage of a simplified or abstracted style with higher spiritual content. Prominent among these was a group who called themselves The Nabis, after the Hebrew word for “prophet.” They were influenced by the Theosophist Edouard Schuré, whose book Les Grands Initiés (1889) recounts the esoteric wisdom of an eclectic group of spiritual “initiates,” including Krishna, Hermes, Moses, Pythagoras, Plato, and Jesus.

Paul Sérusier’s Portrait of Paul Ranson shows the Nabi artist in an elaborate blue-and gold robe, holding a gold staff decorated with symbols, and reading from a medieval-style illuminated manuscript. Behind him a red circle creates a mystic halo, and also shows the flat bright colors and abstract designs favored by the Nabis.

Although the juxtaposition of Ranson’s 19th century pince-nez, waxed mustache, and well-trimmed goatee with this Medieval and esoteric regalia is somewhat incongruous (and may well have been intended to be tongue-in-cheek), it does demonstrate the spiritual aspirations of the group.

Spiritual visions

Theosophists often claimed that the “initiated” had an ability to directly perceive spiritual manifestations in the world around us. The Besant and Klint works with which we began were the result of such visions. Besant was a medium who was able to perceive color auras or “thought-forms” emanating from individuals that revealed their emotional and spiritual state. The upper pink cloud of “vague pure affection” was seen issuing from someone who was “happy and at peace with the world, thinking dreamily of some friend,” while the one below shows affection intermixed with “the dull hard brown-gray of selfishness,” and thus indicates affection based upon the pleasure of favors received or anticipated [1].

Klint was a member of a group of five women in Sweden who used séances to communicate with the spirits of deceased Mahatmas in order to recover lost wisdom. She claimed that her series of Paintings for the Temple were

…painted directly through me [by these spirits], without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.as quoted by Moderna Museet

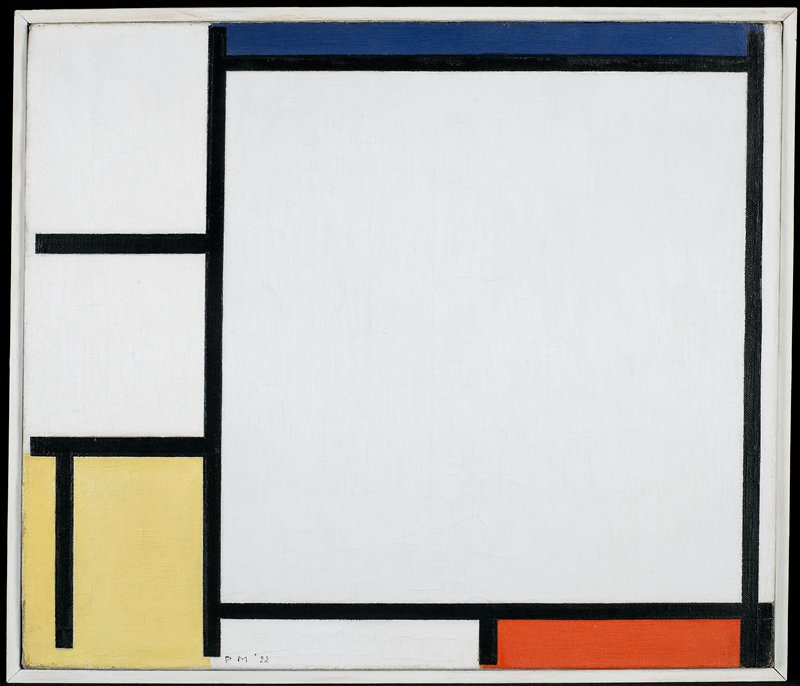

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Blue, Red, Yellow, and Black, 1922, oil on canvas, 41.9 x 48.9 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Theosophy and Modernism

Theosophy aligned so well with modern art because it validated the idea that European art’s traditional naturalistic style, which (they believed) merely imitates the surface appearances of nature, is inadequate to explain the deep underlying mysteries of the universe. For the theosophists and the artists who were influenced by them, there are truths inaccessible to the scientific method, and a meta-reality beyond the reach of human perception. Theosophy was a source for many artists who sought higher spiritual truths and a non-perceptual basis for their art, and it validated the idea that a fully spiritual art would leave behind all basis in natural objects and would be fully abstract.

Vassily Kandinsky, Study for Painting with White Form, 1913, watercolor, opaque watercolor and ink on paper, 27.6 x 37.8 cm (MoMA)

It is important to recognize, however, that the styles inspired by Theosophy were remarkably diverse, ranging from Mondrian’s rigidly rectilinear geometry to Kandinsky’s improvisational painterly exuberance. The spiritual meta-reality appeared to different artists in remarkably diverse guises.

Theosophy was also undoubtedly compelling to some artists because of its suggestion that the artists themselves could be counted among the initiates, and that they had a mission to enlighten humankind. In his treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1909), Kandinsky imagines the spiritual evolution of humankind as an upward-moving triangle articulated with different levels of enlightenment, from the ignorant masses at the base to the few initiates at the apex. Those toward the top of the triangle cannot be understood by those below them – thus helping to explain the poor critical reception of innovative modernist art such as Kandinsky’s – but nonetheless are leading humanity upward in their spiritual evolution.

Notes:

- Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbetter, Thought Forms, New York: John Lane, 1905, pp. 40-42.

Additional resources:

Sixten Ringbom. “Art in ‘The Epoch of the Great Spiritual’: Occult Elements in the Early Theory of Abstract Painting.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. vol. 29 (1966), pp. 386–418.

Maurice Tuchman, et al. The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 (New York, London, and Paris: Abbeville Press, 1986).