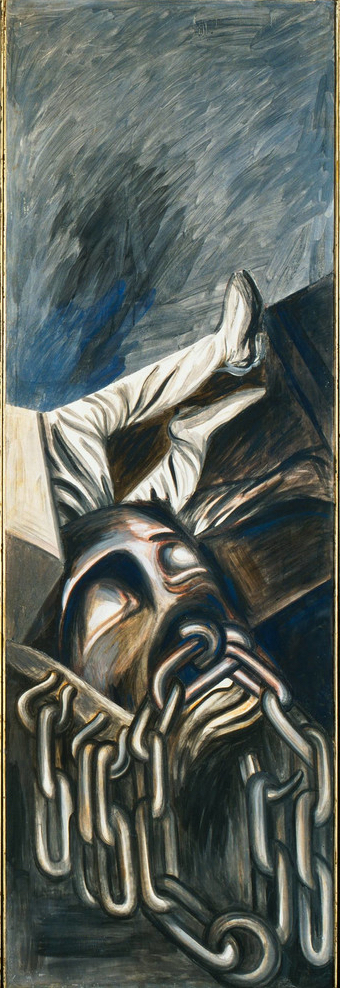

José Clemente Orozco, Dive Bomber and Tank, 1940, fresco, six panels, 275 x 91.4 cm each, 275 x 550 cm overall (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Humanity

José Clemente Orozco painted the mural Dive Bomber and Tank in front of visitors at The Museum of Modern Art in 1940. The fresco was made in conjunction with the exhibition, “Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art,” and Orozco captivated his audience over a frantic ten-day period through his performance and his powerful imagery.

Detail, José Clemente Orozco, Dive Bomber and Tank, 1940, fresco, six panels, 275 x 91.4 cm each, 275 x 550 cm overall (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Against the backdrop of World War II and the infamous blitzkriegs of the Nazis, Orozco depicted the effects of modern warfare on humanity. Interestingly however, and because weapons of war dominate most of the composition, any hint of the human figure is lost, except for three human legs that sprout from the debris, and upon close inspection three metallic human faces—or masks—chained to the debris. These faces are buried under large, heavy, industrial weapons, that include tank treads and the disassembled parts of a bomber. Through this superimposition, Orozco makes clear the triumph of war over humanity, or as he put it “the subjugation of man by the machines of modern warfare.” [1]

Abstraction

For all the certainty of this statement, there is significant ambiguity in the painting. The upturned legs could be those of helpless victims or those of the bomber pilots. The artist purposely leaves these questions unanswered, offering little narrative detail or visual clarity. Indeed Orozco claimed that these panels could be arranged in any order (a Surrealist strategy), and not necessarily in sequential order (as they are usually shown at MoMA). As a result of their interchangeability, the panels each function independently though collectively they create multiple abstract compositions.

His interest in abstraction distinguished Orozco from his closest contemporaries, Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros (together these muralists were known as Los Tres Grandes, “the three great ones”). These abstract tendencies can be seen in Dive Bomber and Tank in the relative lack of detail, expressionist brushstrokes, repetition of form, and monochromatic palette.

The attention to the circular forms of the chain links and metallic bolts, and the rectangular shape of the tank treads create a composition that is at once representational and abstract. The fact that these forms are disconnected from each other, a result of the dismembered state of the bomber and tank, and the logistical arrangement of the panels, render the mural even more abstract.

War

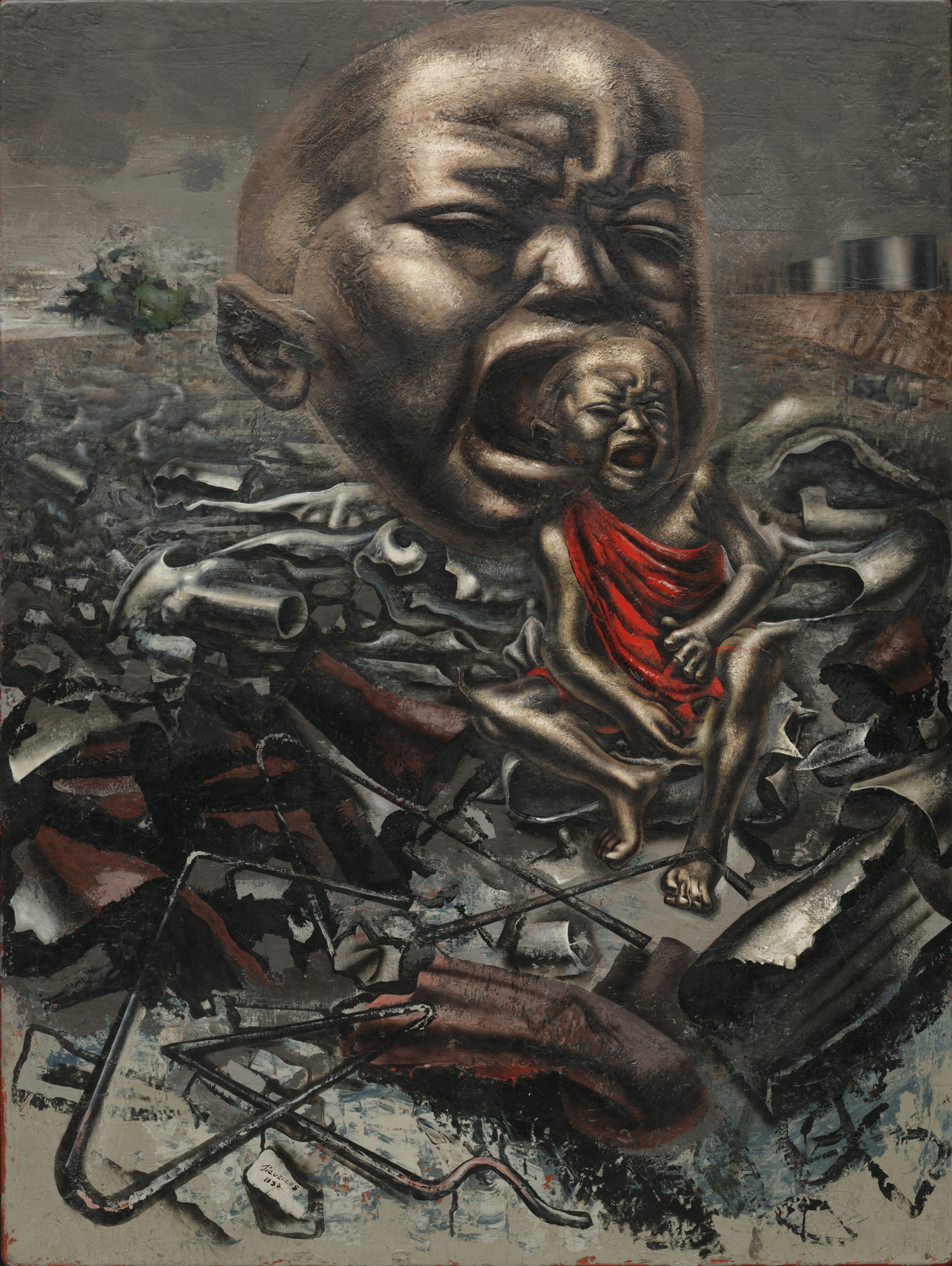

David Alfaro Siqueiros, Echo of a Scream, 1937, enamel on wood, 121.9 x 91.4 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

While Orozco stated that this mural had “no political significance,” war was the dominant reality in 1940 and focused the attention of other artists at the time. Pablo Picasso had documented the effects of the Spanish Civil War in his painting Guernica in 1937—the same year that David Alfaro Siqueiros painted the powerful Echo of a Scream. Picasso’s Guernica had been on exhibit at MoMA from late 1939 to January 1940 and the Siqueiros had been in MoMA’s collection since 1937. Together these artists articulated a clear anti-war message that rivaled the more traditional heroic narratives common in history painting. Devoid of the geographical specificity that characterized Picasso’s Guernica, Orozco—like Siqueiros—represented a condemnation of war that can be easily applied to any place or people, fitting given that violence was now world-wide. The fact that Dive Bomber and Tank lacks any specific political symbols or historical details makes the mural that much more universal.