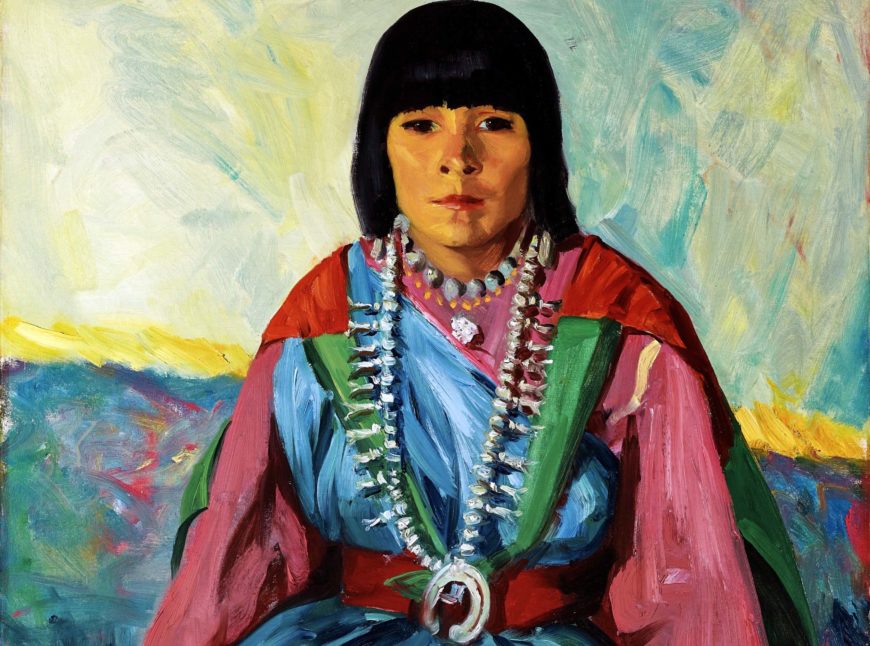

Robert Henri, Tom Po Qui (Water of Antelope Lake/Indian Girl/Ramoncita), 1914, oil on canvas; 40-½ x 32-½ inches (Denver Art Museum)

Robert Henri produced this striking portrait of Ramoncita Gonzales (Tom Po Qui) (Tewa, San Juan Pueblo) in 1914, at the onset of the First World War. The date of the painting, the vibrancy of Henri’s palette, and the sitter’s Indigenous Pueblo identity are key to unpacking the significance of the work.

Robert Henri, Snow in New York, 1902, oil on canvas, 81.3 x 65.5 cm (National Gallery of Art, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 )

Henri was, by this time, an important figure in the American art world, and was recognized as a leading figure in the development of the Ashcan School style of painting. He had been the main organizer of a renegade group of artists known as The Eight. Tom Po Qui was painted six years later, relatively late in his career, and here we see a shift in style.

A new vibrancy

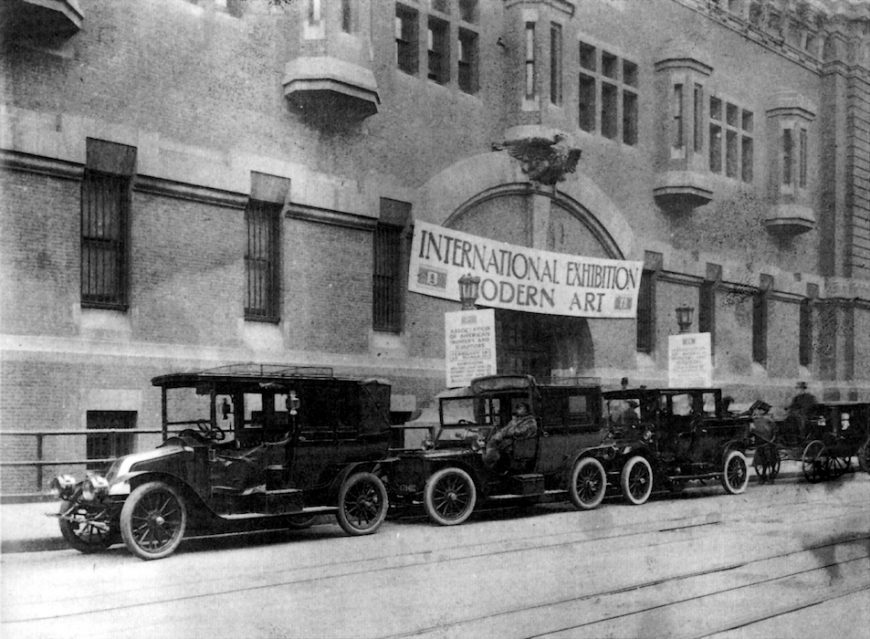

Just a year prior to the production of this work, the New York art world had been rocked by the 1913 Armory Show (also known as the International Exhibition of Modern Art), which was the first major exhibition of modern art staged in the United States. While some American artists (including Henri) were included in the show, it was the Europeans who really shocked audiences with their avant-garde styles, including Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism. For American viewers who had only recently become accustomed to the gritty realism of Henri and his fellow Ashcan School painters, the experimental European works were shocking.

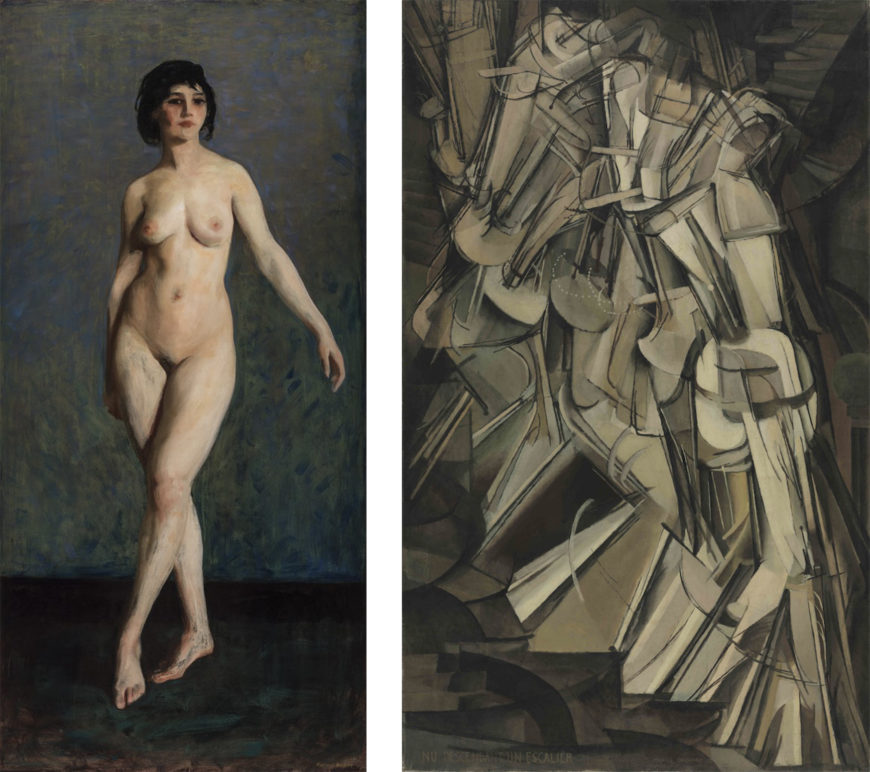

left: Robert Henri, Figure in Motion, 1913, oil on canvas, 196.2 x 94.6 cm (Terra Foundation for American Art); right: Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912, oil on canvas, 151.8 x 93.3 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

In fact, one of Henri’s contributions to the show, Figure in Motion, is often compared to Marcel Duchamp’s famed Cubist composition Nude Descending a Staircase (No.2) as a way to underscore the resolutely representational character of American Realism with the flat planes and abstracted quality of the European avant-garde. While Henri’s work remained figurative in the years after the Armory show, his technique grew looser and his palette became lighter and brighter, likely due in part to experiencing Fauvist works at the Armory.

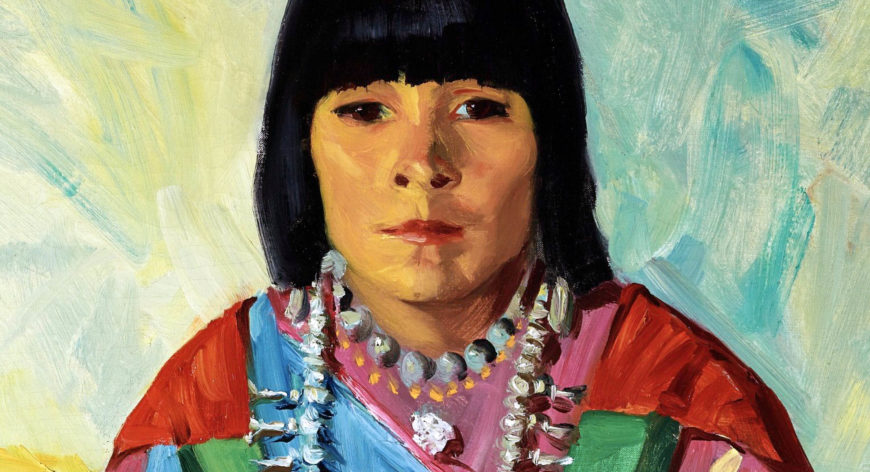

Robert Henri, Tom Po Qui (Water of Antelope Lake/Indian Girl/Ramoncita) (detail), 1914, oil on canvas; 40-½ x 32-½ inches (Denver Art Museum)

However, the vivid colors of Tom Po Qui cannot be explained by exposure to European modernist styles alone; that Henri was in California when he painted this canvas is also important. New York-based Henri typically spent summers abroad, traveling to various European locales (significant previous trips included Ireland, Holland, and Spain). However, World War I broke out in the summer of 1914, which made international voyages untenable. Like many Americans whose travel plans were restricted to domestic trips, Henri turned his eye westward. He took the train out to California, settling for the summer months in La Jolla.

Robert Henri, Tom Po Qui (Water of Antelope Lake/Indian Girl/Ramoncita) (detail), 1914, oil on canvas; 40-½ x 32-½ inches (Denver Art Museum)

Henri was particularly drawn to the intense light of southern California, declaring the conditions ideal for painters. His affinity for this light can be seen in the portrait of Tom Po Qui, where the backdrop of the painting is not the dark, interior spaces common in his earlier work, but rather a loosely-painted setting evocative of the sunlight-dappled coastal region where he found himself. The patchy brushwork and bright colors may show evidence of the influence of European modernists such as Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse, but also the impact of working out west.

“My People”

Henri was not only attracted to the light of California; he was also drawn to the diverse population of the area. Throughout his career, Henri was invested in finding new and interesting people to paint, seeking out models of varying social positions, professions, regions, and ethnicities. In California, he was especially interested in finding sitters of what he understood to be diverse racial identities. During what would eventually be three trips to the area, he painted Black, Chinese American, Mexican American, and American Indian sitters. In a 1915 article predicated on these works, Henri stated: “I was not interested in these people to sentimentalize over them, to mourn over the fact that we have destroyed the Indian, that we are changing the shy Chinese girl into a soubrette, . . . I am looking at each individual with the eager hope of finding there something of the dignity of life, the humor, the humanity, the kindness.” [1]

left: Robert Henri, Sylvester, 1914, oil of canvas, 81.2 x 66. cm (Terra Foundation for American Art); right: Robert Henri, Tam Gan, 1914, oil on canvas, 60.96 x 50.8 cm (Albright-Knox Art Gallery)

Today we read his rhetoric as problematically racist and patronizing, particularly in light of the article’s proprietary title, “My People.” But Henri’s desire to paint these sitters as dignified individuals nonetheless defies the more virulent racial stereotyping typical of the era, even as his approach could devolve into exoticism.

Robert Henri, Tom Po Qui (Water of Antelope Lake/Indian Girl/Ramoncita) (detail), 1914, oil on canvas; 40-½ x 32-½ inches (Denver Art Museum)

Tom Po Qui is a prime example of such portraiture. On the one hand, the work appears to present Gonzales as an ethnic type, her colorful Native clothing and dazzling silver jewelry highlighted in a manner that seems to render her a decorative object, presented to be consumed by non-Native audiences eager to see depictions of exotic American Indian culture. Yet Gonzales stares out of the canvas with self-possession, evenly meeting the viewer’s gaze in a way that disrupts the interpretation of this work as entirely exploitative. The agency of this sitter cannot be ignored, and indeed the historical record regarding Gonzales’s identity as a Pueblo artist and performer in her own right brings further nuance to analysis of this painting.

Painted Desert

Henri painted Gonzales not in La Jolla, but in nearby San Diego, at the site of the Panama-California Exposition, which would open in 1915. The Panama-California Exposition was held between January 1, 1915 and January 1, 1917 in San Diego’s Balboa Park, to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal and to promote tourism in the region. Construction was underway for the Exposition’s various exhibits, including the “Painted Desert,” an ethnographic exhibit with a large-scale reconstructed pueblo that would display hundreds of Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache performers. Organizers asked several Pueblo families to travel from their homes in New Mexico to the site early and to aid in construction. Gonzales was among them, arriving with her cousin Maria Martinez and Maria’s husband Julian. While Julian Martinez served as a construction foreman, Gonzales and Maria Martinez constructed the large pots that served as chimneys in the living spaces for the reconstructed Pueblo. When the fair opened, they would continue producing pottery, this time for sale to the visitors who flocked to the exposition. Tourist interest in Pueblo pottery during this period spurred a revival in the practice, which had almost died out in the late nineteenth century.

Unknown photographer, Maria Martinez and Ramoncita Gonzales making pottery, Painted Desert Exhibit, Panama-California Exposition, 1915 (photo: San Diego Museum of Man)

Fairgoers occasionally purchased pots, but they also visited the Painted Desert exhibit to simply observe the Indigenous peoples residing there, undertaking activities deemed traditional—including pottery production. Visitors watched as Maria Martinez and Ramoncita Gonzales shaped and fired their vessels, with Julian Martinez providing the painted designs. These Pueblo figures were artist/performers; they agreed to present themselves as Native peoples living in a traditional manner in exchange for wages paid by the fair organizers. Likewise, as artists such as Henri visited the fairgrounds in search of models, Pueblo performers agreed to sit, or we might say, perform their traditional identity.

Robert Henri, Tom Po Qui (Water of Antelope Lake/Indian Girl/Ramoncita) (detail), 1914, oil on canvas; 40-½ x 32-½ inches (Denver Art Museum)

Gonzales likely selected her attire for Tom Po Qui; it is the same types of clothing and jewelry that we see her and other Pueblo women wearing when the exposition opened. As customary Pueblo livelihoods were threatened by encroaching white culture, Gonzales and others turned to the production of tourist wares and performance as “Show Indians” as a matter of survival. Images such as Tom Po Qui are reminders of the exploitative and exoticizing practices that led Pueblo people like Gonzales to take up the performance of their Indigenous identity for financial security. It is worth noting however, that simultaneously, this work documented the agency of Native peoples in the early years of the twentieth century, as they adapted Indigenous traditions to the needs of their modern lives.