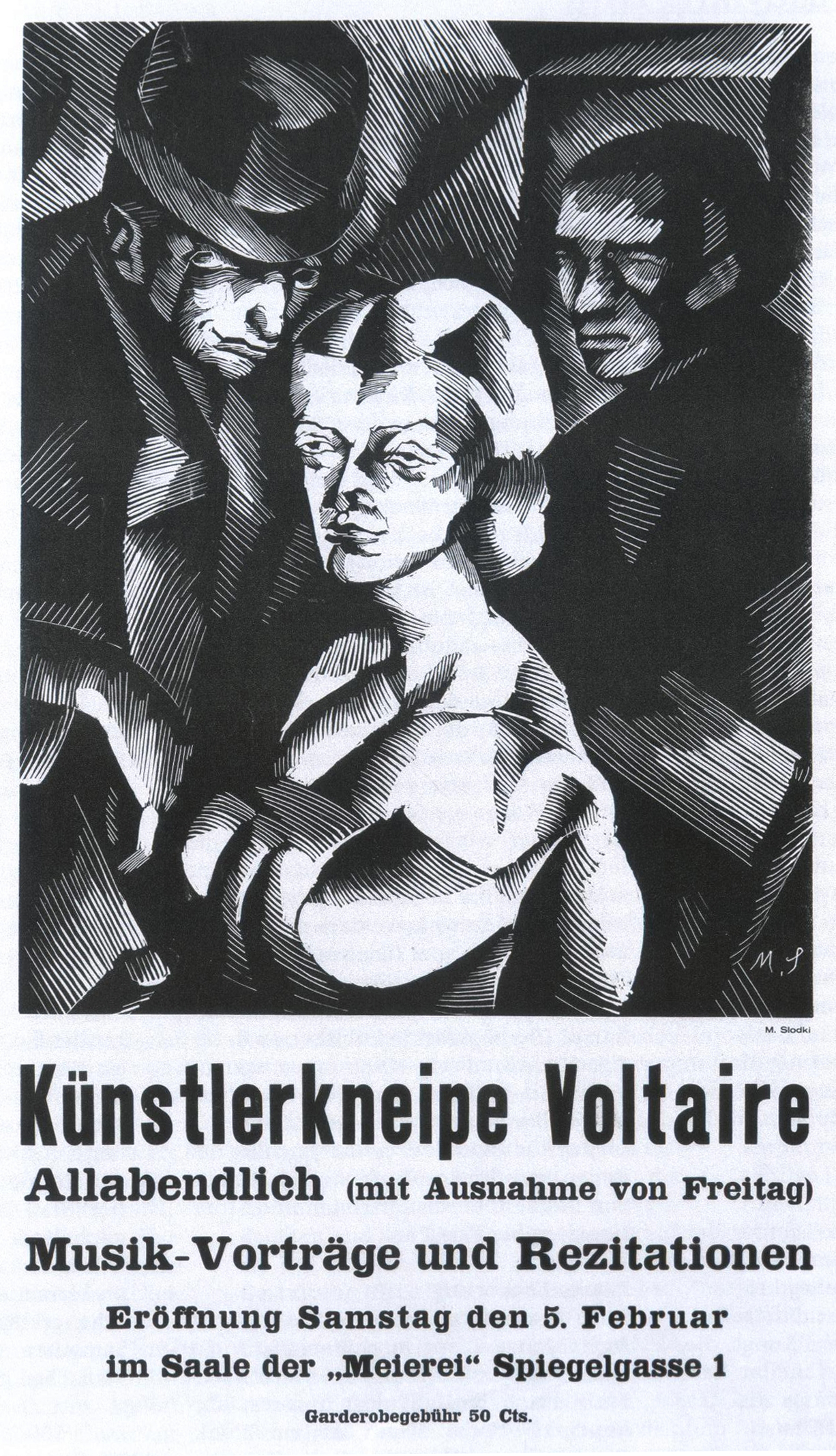

The Dadaists produced a bewildering variety of art, but the roots of Dada were in performance. The movement was founded in 1916 when German writer Hugo Ball and poet/performer Emmy Hennings received permission from the owner of the Meirei café in Zurich, Switzerland to use a small room as a venue for art performances. Ball recorded the opening of the Cabaret Voltaire in his diary on 2 February:

Under this name a group of young artists and writers has been formed whose aim is to create a center for artistic entertainment. The idea of the cabaret will be that guest artists will come and give musical performances and readings at the daily meetings. The young artists of Zurich, whatever their orientation, are invited to [make] suggestions and contributions of all kinds.Translated in Leah Dickerman, ed., Dada (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2006), p. 22.

Artists and writers of many nationalities who had fled to neutral Switzerland to escape World War I responded to this invitation. In addition to Ball and Hennings, the core of the Zurich Dada group included the Romanians Tristan Tzara and Marcel Janco (Iancu) and the Germans Hans Arp, Sophie Täuber, and Richard Huelsenbeck.

Ball and Hennings invited artists “whatever their orientation” and contributions “of all kinds,” setting the stage for a wildly diverse output that included Ball’s poetry, Hennings’ songs, Janco’s masks, Arp and Täuber’s abstract weavings and constructions, and Huelsenbeck’s chants. The disparate group was united by anti-war sentiment as well as general iconoclasm and irreverence, indicated by the name Voltaire, which referred to the 18th-century French satirist of religion and established authority.

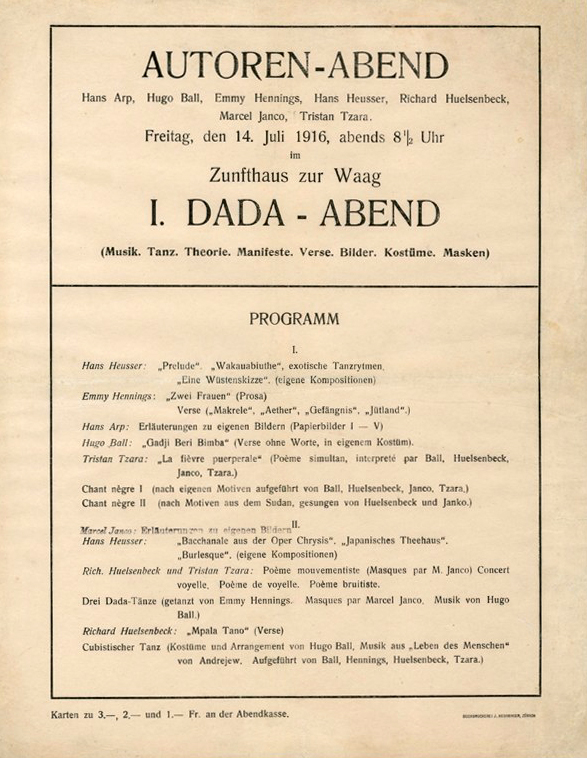

A Dada soirée

Tristan Tzara documented the program of a Dada soirée held on 26 February 1916 in prose as breathlessly cascading and chaotic as the evening itself must have been:

DADA!! the latest thing!!! bourgeois syncope, BRUITIST [noise] music, the new rage, Tzara song dance protest — the bass drum — red light, policemen — songs cubist tableaux postcards Cabaret Voltaire song — simultaneous poem … two-step alcohol advertisement smoking toward the bells / we whisper: arrogance / Ms. Hennings’ silence, Janco declaration. transatlantic art = people rejoice star projected on Cubist dance in bells.Tristan Tzara, “Chronique Zurichoise,” entry for 26 February 1916, in Richard Huelsenbeck, ed., Dada Almanach (Berlin, 1920), p. 11.

Despite its apparent randomness, this is a fairly straightforward listing of the kinds of performances the Dadaists favored, which, like a cabaret variety show, included dance, music, poetry recitations, costumed performances, and audience participation. However, most of these popular art forms were distorted beyond recognition.

Dada poetry

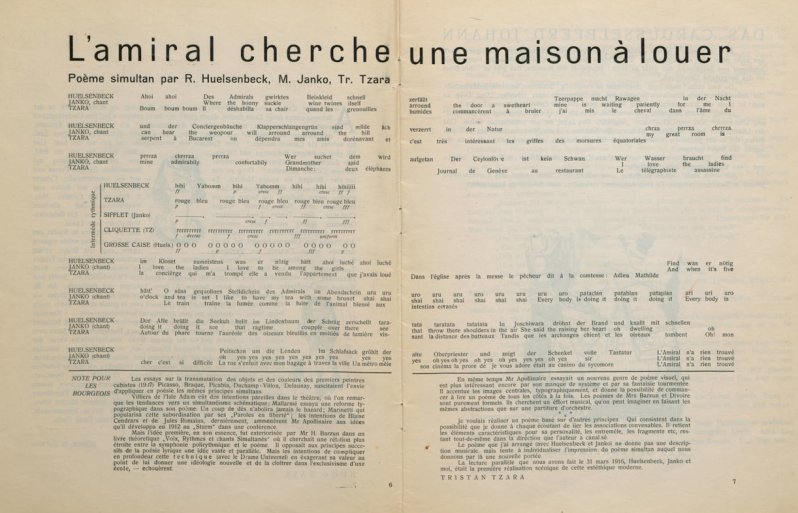

L’amiral cherche une maison à louer text, recited 30 March 1916, as published in the journal Cabaret Voltaire, 1916

For one type of recitation mentioned by Tzara, the “simultaneous poem,” different lines of text were read at the same time by different performers. In L’amiral cherche une maison à louer (The admiral is looking for a house to rent), three voices speak/sing the text simultaneously, Huelsenbeck in German, Janco in English, and Tzara in French, while playing a siren whistle, rattle, and bass drum. The performance provides a sensory and semantic cacophony that is only resolved in the final bleak line, when all three performers together recite in French, “The admiral found nothing.”

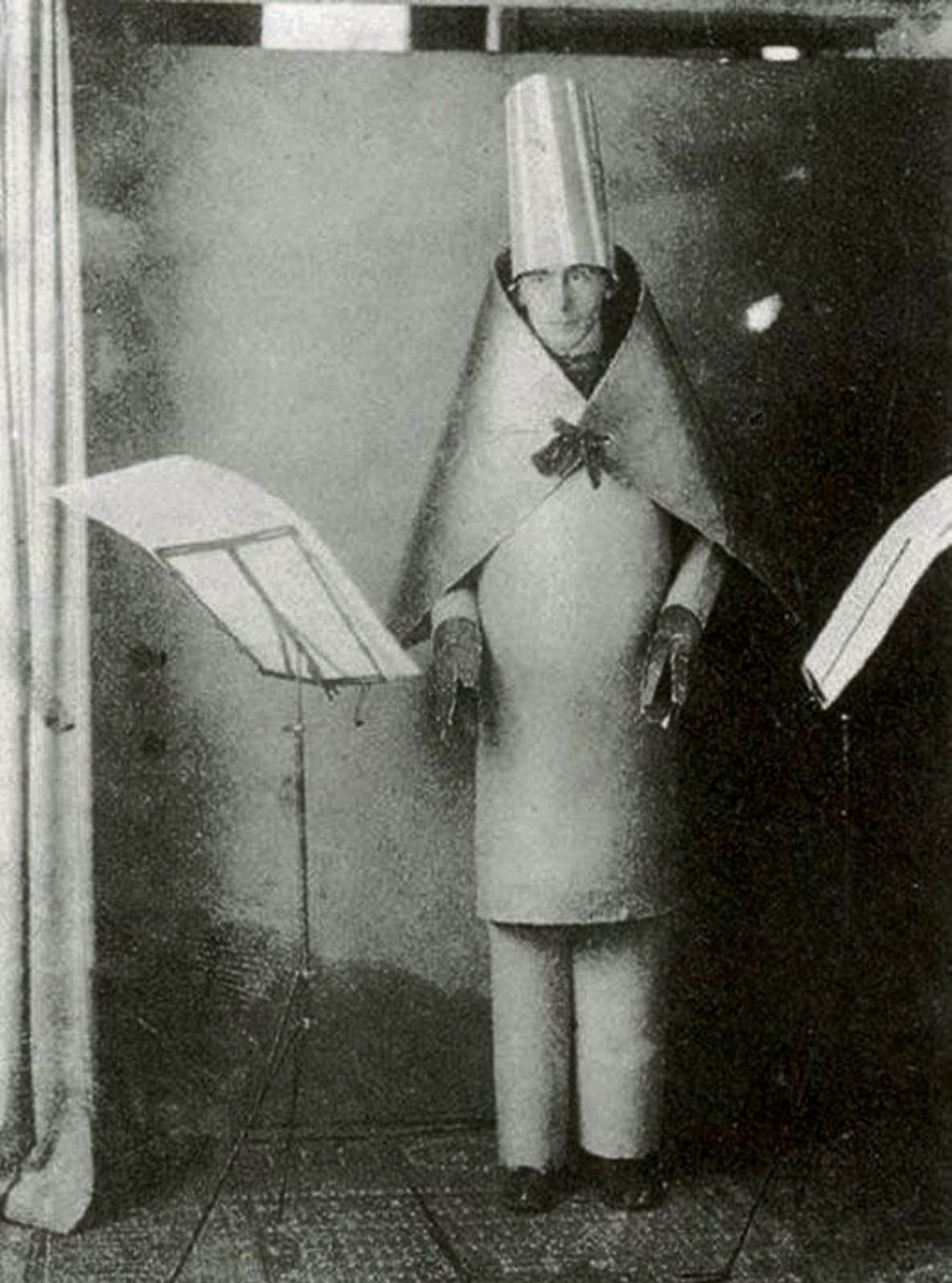

Another type of performance was the sound poem, which was made up of meaningless phonemes rather than words. For example, Ball’s poem Karawane begins, “jolifanto bambla o falli bambla / großiga m’pfa habla horem / egiga goramen / higo bloiko russula huju / hollaka hollala … .”

Ball recited this poem while wearing a cardboard costume vaguely resembling a bishop’s cape and miter that was so restricting he had to be carried on and off stage. The costume combined with the incomprehensible chant (Catholic masses were conducted in Latin at the time), created an obvious satire on religion.

Ball’s own description of this performance also suggests a sort of regression therapy in which he recollects seeing the liturgy as a child:

I do not know what gave me the idea of this music, but I began to chant my vowel sequences in a church style like a recitative … For a moment it seemed as if there were a pale, bewildered face in my Cubist mask, that half-frightened, half-curious face of a ten-year-old boy, trembling and hanging avidly on the priest’s words in the requiems and high masses in his home parish. Then the lights went out, as I had ordered, and bathed in sweat I was carried off the stage like a magical bishop.Translated in Dickerman, ed., Dada, p. 28.

Dada song and dance

More ordinary cabaret fare such as song-and-dance numbers were also distorted. With a gallows humor typical of those caught up in the horror of World War I, Emmy Hennings sang an altered version of a popular soldier’s marching song, ‘This is how we live [So leben wir],’ as “This is how we die, this is how we die, / We die every day, / Because they make it so comfortable to die.”

Dada soirées also included performers in Janco’s so-called African masks dancing and chanting Huelsenbeck’s African-sounding songs. The chants were at first entirely invented (with each verse ending in “umba, umba”), but later included some authentic African and Maori borrowings. Like Hugo Ball’s sound poems, such performances were intended as repudiations of Western rationalism and civilization, and possibly as invocations of healing primal states.

While the Dadaists’ intention was to valorize non-Western cultures, their “primitivist” performances are today considered problematic. Like many modern artists who embraced “primitivism” the Dadaists appropriated non-Western cultural artifacts without understanding or acknowledging their original values and purposes. They assumed African cultures and peoples were non-rational and tended to generalize all African and Oceanic cultures into a single homogeneous entity.

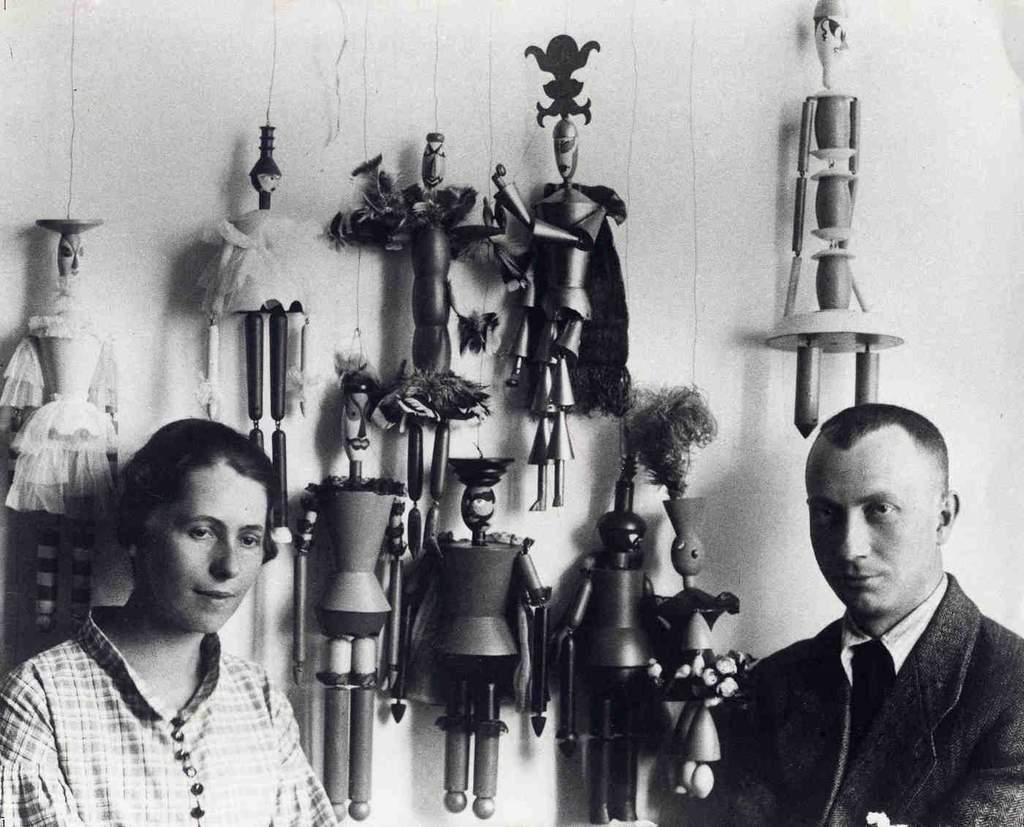

Among her many projects, Sophie Täuber participated in Dada performances as a dancer in a troupe choreographed by Rudolf Laban, who was known for rejecting classical movement in favor of more natural body language. A photograph of her in a pose at the opening of the Galerie Dada while wearing a mask by Janco shows another artistic convention broken by the Dadists. In a typical cabaret the attractive appearance (and implied sexual availability) of the female performers was taken for granted, but as Hans Richter noted in his memoir of Zurich Dada, the masks and costumes hid the “pretty faces” and “slender bodies” of the dancers[1].

Täuber also produced figurative sculpture, mostly reduced to basic geometric shapes either turned on a lathe or constructed out of found materials. The marionettes she produced for a 1918 staging of Carlo Gozzi’s König Hirsch (King Stag), for example, are made of thread spools and other wood scraps jointed with eye hooks. Although not produced in the context of Dada, these marionettes evoke many of the same themes, including the playful use of found materials and the uncomfortable transformation of organic, apparently free human beings into rigidly mechanized automatons.

‘Our cabaret is a gesture’

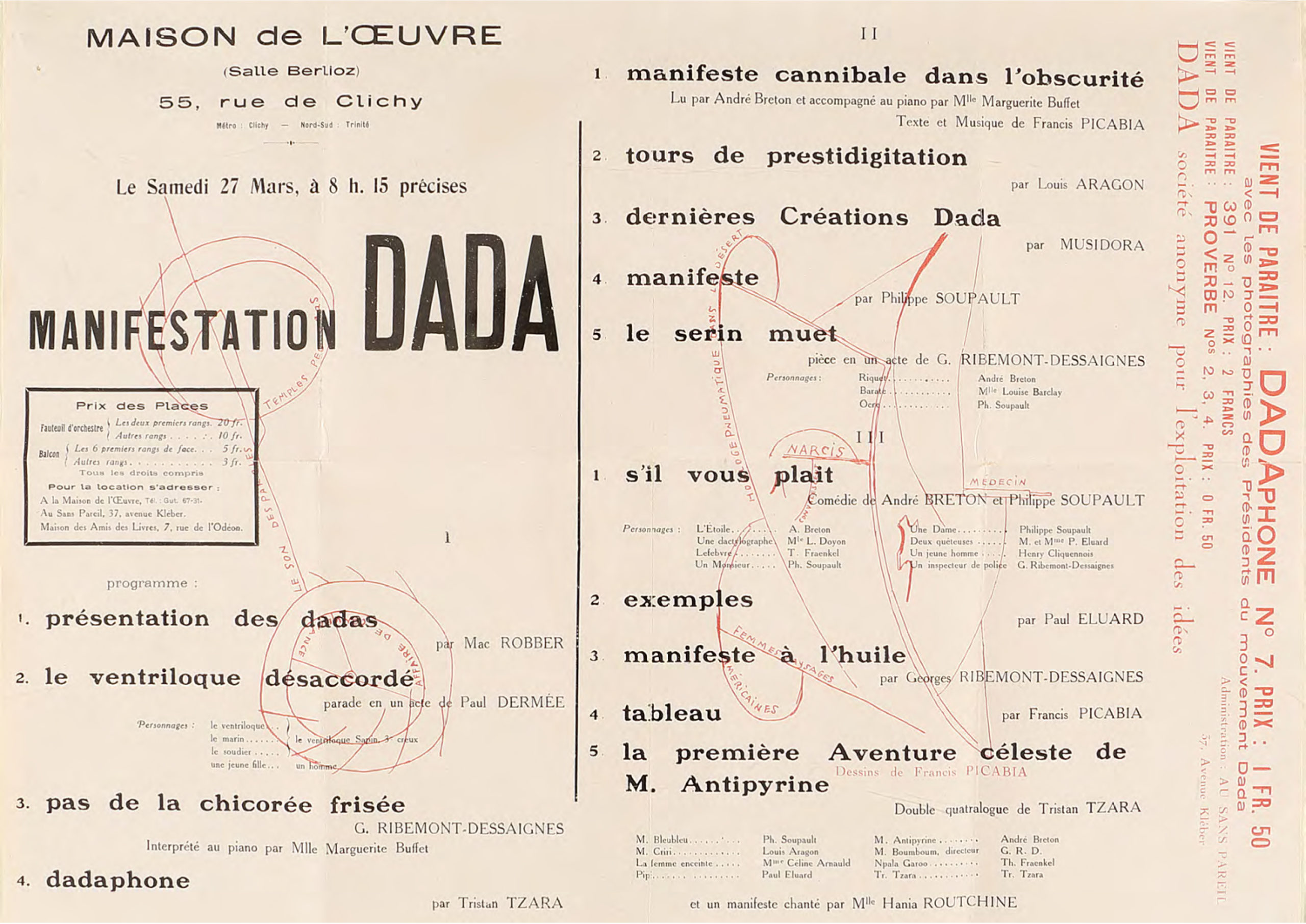

Dada was a cosmopolitan movement at a time of rising nationalism, and it quickly became a global phenomenon, spreading from Zurich and New York to Paris, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, and other locales. The program for a 1920 Paris Dada soirée included a reading of Francis Picabia’s Cannibal Manifesto, which insulted the audience, and a piano piece by Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes titled “March of the Curly Endive,” which was written by chance using a pocket roulette wheel.

What are such performances about? It would violate the absurdist creed of Dada to attempt to submit them to reason and order. Perhaps Hugo Ball put it best when he said, “Our cabaret is a gesture. Every word that is spoken and sung here says at least one thing: that this humiliating age has not succeeded in winning our respect.”[2]

Dada was anti-war, anti-authority, anti-nationalist, anti-convention, anti-reason, anti-bourgeois, anti-capitalist, and anti-art. Performance was of particular value to the Dadaists because its combination of media expanded the potential for multi-sensory and poly-semantic assault; and also because its direct interaction with the public gave it a greater potential to agitate and to shock.

Notes:

- Hans Richter, Dada Art and Anti-Art (London, 1997), pp. 79-80.

- Translated in Dickerman, ed., Dada, p. 25.

Additional resources:

Leah Dickerman, ed., Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, Paris (National Gallery of Art, 2005)

Audio performance of a version of L’amiral cherche une maison a louer

Jody Blake, “Ragging the War: Dada,” in Le Tumulte Noir: Modernist Art and Popular Entertainment in Jazz-Age Paris, 1900-1930 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999), pp. 59-82.