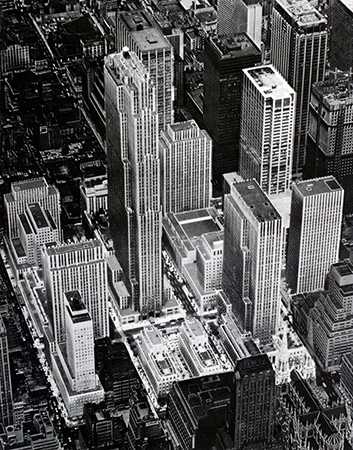

Aerial view of Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a complex of skyscrapers and theaters in New York City developed by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. in the 1930s and designed by a talented committee of architects and planners. It superbly demonstrates how tall buildings can be seamlessly integrated into the horizontal tangle of the city below.

An investment

First conceived in 1927, Rockefeller Center was intended as a mixed use complex that would house the Metropolitan Opera and assorted retail establishments. The opera later withdrew, and was replaced with the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) and its fledgling subsidiary, NBC. Rockefeller wanted a sound return on his investment, but he also wanted to build something that could serve the public good. He was passionate about architecture and he felt responsible for contributing to the urban quality of New York.

Rockefeller Center plan

The design of Rockefeller Center is the product of collaboration between architects with expertise in a variety of fields. Real estate developer John R. Todd, who had been involved in several speculative office projects around nearby Grand Central Terminal, oversaw the project. Todd appointed the firm Reinhard and Hofmeister as general architects, since they had extensive experience designing economic floor plans. Also on the team was the noted architect Harvey Wiley Corbett. Corbett was keenly interested in issues of city planning and traffic flow, and had been involved in the Regional Plan Association’s proposals for urban expansion around the New York region. Working with him was Wallace K. Harrison, who would later collaborate on a number of modern ensembles in New York, including the United Nations and Lincoln Center. Rounding out the group was Raymond Hood, with many skyscrapers under his belt already, including the Gothic revival Chicago Tribune Tower (1922), the elaborate American Radiator Building (1924), and the more restrained Daily News plant (1929). By early 1930, the architects had established the basic setup of Rockefeller Center: a tall building anchoring the middle of the development, fronted by a plaza and flanked by shorter buildings around the periphery of the site.

View of the RCA building Rockefeller Center from the old Union Club, September 1, 1933, 5×7″ safety negative by Gottscho-Schleisner

Cool, unfussy elegance

Raymond Hood’s RCA building (since renamed the GE building and popularly known as 30 Rock) dominates Rockefeller Center. This skyscraper exudes a cool, unfussy elegance. Its limestone façade rises above its neighbors in a series of stepped verticals. Aluminum spandrels create a vertical pattern of lines that emphasize the building’s height. Hood had used a similar approach in his Daily News building, but the striped effect was more subtle here, and the overall proportions more delicate. The building’s profile shifts according to the viewer’s perspective—its north and south façades stretch wide, while its east and west ends present slender fronts to the street. The main approach lies on the east via the long and narrow Channel Gardens (a walk that separates buildings dedicated to France and Britain) that slope gently downward, allowing an unobstructed view as the tower soars upward like the prow of a huge ship.

View of the rooftop gardens at Rockefeller Center from the International Building across to the British Empire Building and La Maison Française along Fifth Avenue (photo: David Shankbone, CC BY-SA 2.5)

The profile of the RCA building was unusual in New York at the time. The city’s zoning regulations required height setbacks, which usually resulted in stepped ziggurat profiles. The slab shape here was relatively new, though it would become more widespread in the city during the postwar period.

View of 30 Rockefeller Plaza (photo: Tobias Schiller, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Streamlined moderne

The building was as efficient as it was elegant, with floor plans designed to maximize rental values. Proximity to windows was important—tenants demanded daylight and ventilation in their office spaces. Careful planning minimized the distance between windows and hallways. Elevators were brought to the center of the building in order to conserve valuable floor space along the perimeter. New high-speed elevators meant fewer banks and thus more rentable floor space. Roof gardens occupied the setbacks below the sixteenth floor—an inexpensive way to add a touch of luxury to the offices, and collect higher rent from those spaces. The streamlined moderne lines of the RCA building typified the style that dominated Rockefeller Center. The towers of the complex cannot be described as avant garde, but they are modern in their simplicity. Their minimalism was due more to cost cutting than architectural experimentation, but nevertheless resulted in a restrained and cohesive complex that primarily relies on massing and proportion for effect.

Lee Lawrie, Wisdom (center), with Light (right) and Sound (left), 1933, painted and gilded limestone, glass (photo: Terry Robinson, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Art and architecture

The architects did, however, welcome the addition of sculpture and paintings to their buildings, both inside and out. To name but a few examples, Lee Lawrie’s rich Art Deco panels on the RCA building depicted allegorical figures of light and sound; Hildreth Meiere’s panels on Radio City Music Hall rendered stylized theatrical muses in bold colors. Lawrie collaborated with sculptor Rene Chambellan on the figure of Atlas in front of the International Building, and Paul Manship’s golden Prometheus lounges in the sunken plaza at the base of the RCA building.

Paul Manship, Prometheus, 1934, gilded bronze, 18 feet high (photo: Rev Stan, CC BY 2.0)

The most famous work in the center no longer exists—Diego Rivera’s frescoes in the lobby of the RCA building were destroyed when the Mexican muralist refused to tone down the anti-capitalist images of his paintings. Rockefeller’s son Nelson had approved the commission; he was an enthusiastic patron of contemporary artists (in this regard, he took after his mother, Abby Aldrich, one of the founders of MoMA). This time, though, his affinity for the avant garde backfired.

Diego Rivera, Man at the Crossroads (in progress), 1932-34 (destroyed) © Banco De Mexico, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums Trust

A “city within a city”

At its heart, Rockefeller Center excels at integrating the vertical city with the horizontal one. It offers layered paths of circulation for the pedestrian and vehicular traffic generated by its many tenants. Small private streets cut into the larger grid of Manhattan to facilitate pedestrian circulation around the crowded plaza. Also crucial to keeping people moving is the Center’s underground concourse, which links every building in the complex to a subterranean shopping center and, ultimately, the subway. Rockefeller Center’s planners envisioned a “city within a city,” and the shops in the concourse meant that office workers could get what they needed without venturing far. The presence of the subway was deliberate too. The center’s transportation committee worked with the city so that its new Sixth Avenue subway line could serve the huge numbers of workers commuting to the complex. Finally, an elaborate network of garages and underground ramps accommodates trucks, facilitating shipments without further congesting the bustling streets of midtown Manhattan.