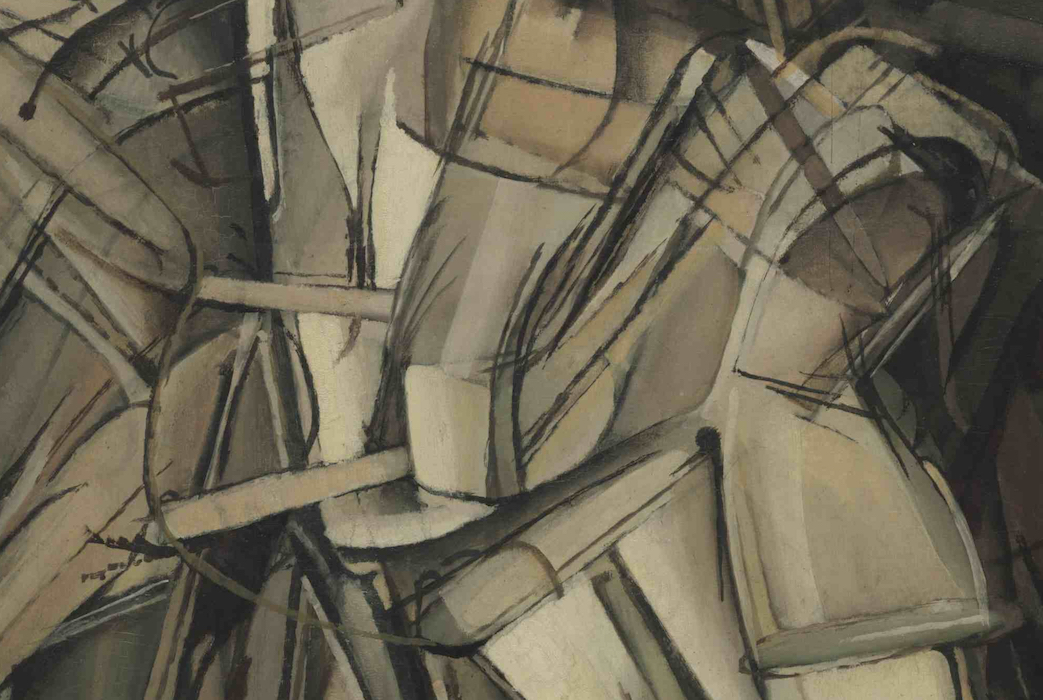

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) , 1912, oil on canvas, 57 7/8 x 35 1/8 (151.8 x 93.3 cm) (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

When the French artist Marcel Duchamp arrived by ship to New York in 1915, his reputation, as the saying goes, preceded him. Two years earlier, in 1913, after an inauspicious debut in France, Duchamp sent his painting Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) to America. His now famous depiction of a body in motion walking down a narrow stairway quickly drew outrage from a public unfamiliar with current trends in European art, and became a succès de scandale (success from scandal) that launched Duchamp into the American spotlight. But why was the painting so shocking?

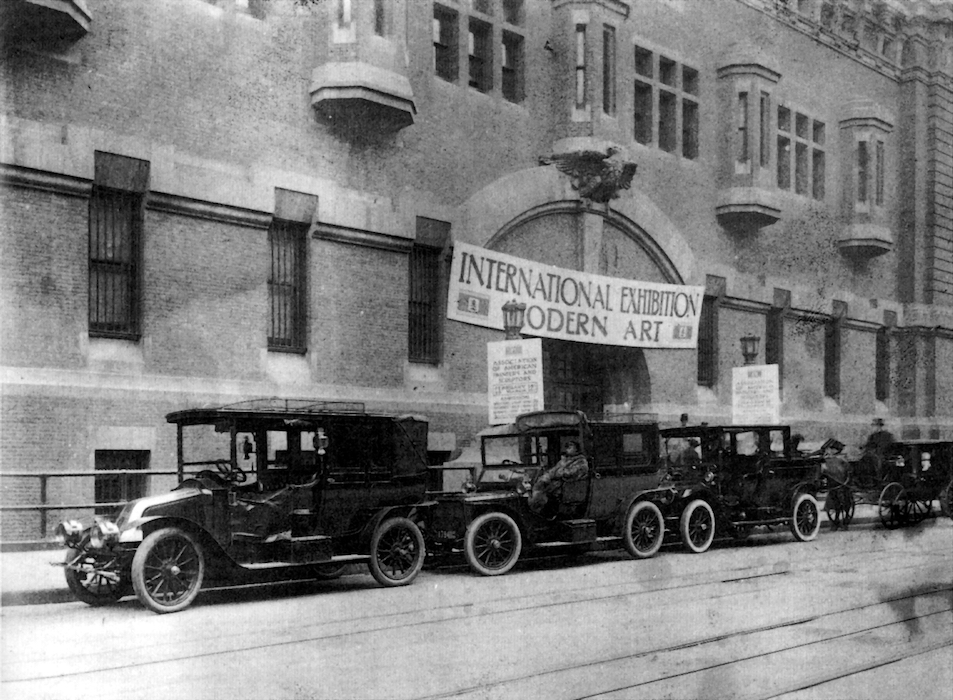

The 1913 exhibition, dubbed “The Armory Show” for its installation in New York City’s 69th Regiment Armory, proposed to survey modern art from Romanticism of the early nineteenth-century to Cubism of the present.

Entrance to the New York City Armory Show, 69th Regiment Armory, New York City, 1913 (public domain)

The group that organized the 1913 exhibition called themselves the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. The sprawling exhibition also included American art and no doubt the organizers hoped that they might promote the work of an American vanguard in the company of illustrious European modernists. All that was quickly forgotten however, as it was Duchamp’s painting that captured attention as the exhibition toured the country. The Armory Show also had the unfortunate effect of showcasing the provincialism of American artists who seemed to paint as if nothing had changed since the Realist and Impressionist movements of the nineteenth-century. In the face of this realization, the American artist William Glackens , one of the exhibition’s organizers wryly lamented, “we have not yet arrived at a National Art.” [1]

Detail, Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) , 1912, oil on canvas, 57 7/8 x 35 1/8 (151.8 x 93.3 cm) (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

As the exhibition toured the country, Duchamp’s painting captured widespread attention for its unconventional rendition of the nude. He positioned the figure — its upright stance reiterated by the vertical orientation of the canvas — in a descending diagonal from upper left to lower right. A tangle of shattered geometric shapes suggest the stairs in the lower left corner of the composition while rows of receding stairs at the upper left and right frame the strangely multiplying female form as she descends. But what a descent! The figure recalls the whirling of a robot promenading down a set of stairs as if in some sort of futurist movie, or perhaps a magic lantern show — a popular form of image projection in the years before the development of cinema.

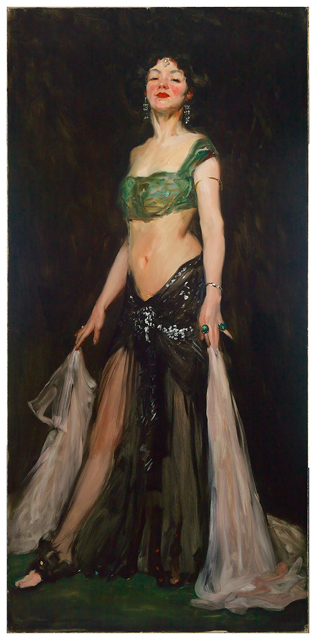

Robert Henri, Salome Dancer , 1909, oil on canvas, 77 x 37 inches / 195.6 x 94 cm ( Mead Art Museum, Amherst College )

Duchamp’s painting was certainly a far cry from what passed as modern painting in the United States at that time. One of the most progressive movements was the Ashcan School , whose members used gritty palettes in expressive renderings of city street scenes, immigrant subjects, and other urban themes that seemed shockingly modern. Robert Henri’s Salome(left) for example, shows an actress striding across a narrow stage in a rather brazen manner. Her head tilts back as she gazes at the viewer and her hands sweep aside the folds of her skirt to reveal her legs. In contrast to Henri, Duchamp’s subject matter is nearly indecipherable. His figure registers as female because of the convention, at least in recent years, that expects most nudes in art to be women. Moreover, the style was an extreme distortion of even the most contemporary kind of realism at the time. It was, perhaps, for these reasons that the painting challenged audiences, such as the uncomprehending critic who described Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) as “the explosion of a shingle factory.” [2]

Like much European modernism (think Cubism, Futurism or Orphism), the painting abandoned any resemblance to nature. Its relatively monochromatic palette of warm browns and ocher subtly tinged with a grayish blue-green is typical of early Cubist paintings by Pablo Picasso and George Braque, who had wanted to minimize the optical effects of color and emphasize, instead, a revolutionary new conception of space. In this regard at least, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) did not disappoint.

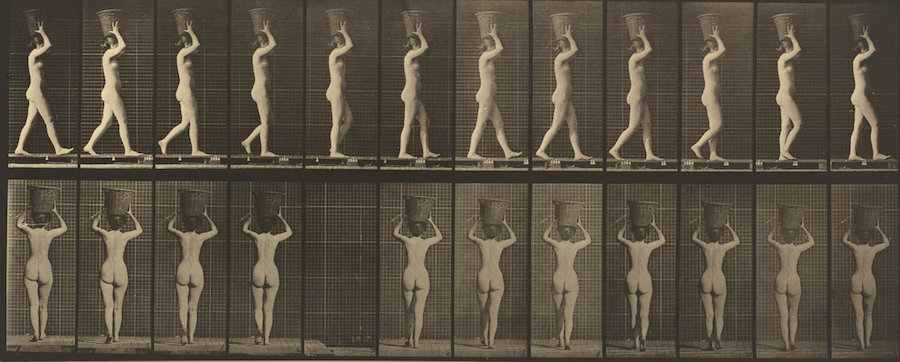

Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) did not waiver from its origins in Cubism. But, the unusual sense of motion conveyed in the painting may reflect an additional influence in the photography of Eadweard Muybridge (below) or Étienne-Jules Marey, who had invented a camera shutter in 1882 that allowed for an early version of time-lapse photography. Notice how the figure approximates the blur one might see with time-lapse imagery. Even painters of the Puteaux group, whom Duchamp had known in France, disapproved (they were interested in furthering the original Cubist investigations into pictorial space and perception of Picasso and Braque). In Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), Duchamp had welded a cubist style of shattered picture planes to the kind of painting being done by the Italian avant-garde movement Futurism, typified by Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space. The painting, as a result, is sometimes referred to as a Cubo-futurist work.

Eadweard Muybridge, Walking and Carrying at 15-lb. Basket on Head, Hands Raised, c. 1887, collotype, 16.8 x 41.8 cm (National Gallery of Art)

However unresponsive the reception for Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) was in France, it became a charged symbol of the modern in America. The female form had, of course, suffered avant-garde assault for some time in Europe reaching as far back as Manet’s Olympia (1863), which showed a nude female reclining across a flatly painted interior. Matisse and his followers had even further abstracted the figure in their fauvist paintings. But in America, the lingering traces of the classical style with its idealizing forms still prevailed even among more contemporary painters. Duchamp turned a venerable subject—the female nude, and all it embodied about western culture and traditions of beauty—into something monstrous and worse, something machine-like. As in his later readymades—which turned ordinary commercial objects into works of art—Duchamp embraced the very thing art was supposed to reject: the cold logic of industrial production.