Revolutionary soldiers (detail), Diego Rivera, “Distribution of Arms,” Court of the Fiestas, third floor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What is the intersection of art and politics? When and how does art serve as propaganda or as a political force for change? For Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, all art was propaganda. In his autobiography he wrote,

Every strong artist has been a propagandist. I want to be a propagandist and I want to be nothing else. I want to be a propagandist of Communism and I want to be it in all that I can think, in all that I can speak, in all that I can write, and in all that I can paint. I want to use my art as a weapon.[1]

This idea of art as a weapon was prominent in the 1920s and 1930s when there was an international discourse on how art could best serve a political cause. Rivera was painting at a time when artists were exploring the artistic possibilities of how their work could further the political project of postrevolutionary Mexico and, for Rivera and other Communist artists, the political project of international socialism. As a Communist, Rivera saw his murals as playing an important role in the class struggle, writing,

In order to be good art . . . it must be revolutionary art, art of the proletariat.[2]

Today it might be difficult to imagine an artist being commissioned by the government to paint mural scenes that advocate for an international workers’ revolution on the walls of a state building, but that is exactly what Diego Rivera did at the Ministry of Public Education (Secretaría de Educación Pública, or SEP) in Mexico City.

Rivera was not just any artist, however, and by 1928 he had attained an international artistic reputation that afforded him protection from censorship that other artists might have faced and this enabled him to be more explicitly political in his mural work. Executed over the course of five years, the mural cycle at the SEP offers the chance to study the evolution of Rivera’s politics and style in response to changing political conditions and an influential trip to the Soviet Union in 1927.

Diagram of the 3rd floor mural program for the Court of Fiestas, Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (underlying map © Google)

The SEP cycle

Rivera was commissioned to paint 117 panels at the SEP building that covered two courtyards and three levels. The courtyards were divided thematically into a “Court of Labor” and a “Court of Fiestas.” The initial phase of the mural cycle (the first and second floors painted in 1923–24) represents the traditions and culture of the Mexican people, as well as the central role of agrarian reform (redistribution of agricultural land) in the Mexican Revolution. Rivera depicted the role of the arts in advancing the revolutionary struggle in the stairwell and third floor “Court of Labor” murals.

Diego Rivera, Court of the Fiestas, third floor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

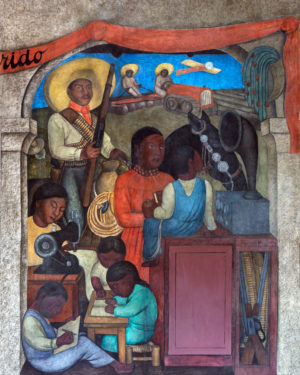

In the third floor “Court of Fiestas,” Rivera looked increasingly to the future and the proletarian revolution that would further the project of the agrarian revolution. In the third floor “Court of Fiestas,” Rivera painted a “Corrido of Agrarian Revolution” that depicted the results of the 1910–20 Mexican Revolution, before painting the “Corrido of the Proletarian Revolution” after his trip to the Soviet Union in 1927, where he rendered a socialist revolution that was international and industrial.

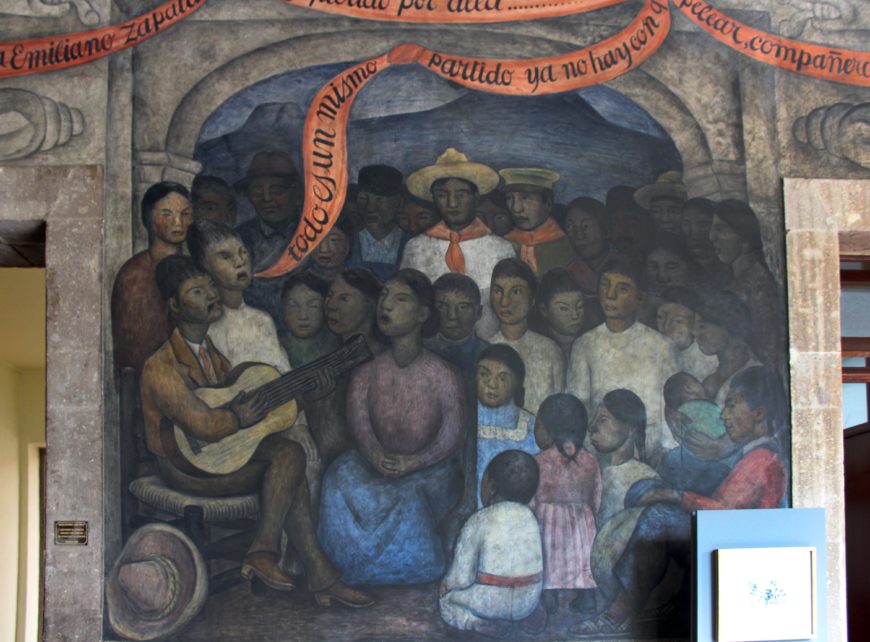

Diego Rivera, beginning of the “Corrido of the Agrarian Revolution,” Court of the Fiestas, third floor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Court of Fiestas

Corridos are a Mexican narrative ballads that were popular during the Revolution. In Rivera’s murals, the lyrics to the corrido are represented upon a painted red banner that unites the various panels as well as the two distinct corrido cycles. The cycles are further linked through the illusionistic archways that Rivera painted to frame each scene. Throughout the cycle, Rivera renders figures and forms partially outside the frame, which further brings the revolutionary subject matter into the space of the viewer.

Corrido of the Agrarian Revolution

The “Corrido of the Agrarian Revolution” begins with a woman (modeled after the singer and activist Concha Michel) singing the corrido to a group of people in the countryside. Ribboned lyrics emerge from her mouth before continuing along the top of the remaining walls. This cycle depicts scenes that reflect the successes of the Mexican Revolution.

Diego Rivera, Literacy (left) and The Eras (right), “Corrido of the Agrarian Revolution,” Court of the Fiestas, third floor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photos: Megan Flattley, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Scenes such as Literacy, where revolutionary soldiers are shown reading and a teacher is distributing books, represent the centrality of education in the postrevolutionary project (and reflects on the function of the building where the mural was created) by depicting the campaigns to spread education throughout the nation.

Rivera depicts farmers, or campesinos, as foundational for the success of post-revolutionary Mexico in panels such as The Eras, where farmers are shown transporting large bundles of wheat. The way that the curves of their laboring backs echo the curved bundles indicates the harmony of the worker with the land. The corrido lyric above this scene reads: “Just as the soldiers have served for the war they give fruit to the nation and work the land,” indicating the unity of the efforts of soldiers and campesinos, a theme that is repeated throughout the cycle.

Diego Rivera, The Capitalist Dinner (left) and Wall Street Banquet (right), “Corrido of the Agrarian Revolution,” Court of the Fiestas, third floor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photos: Megan Flattley, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Diego Rivera, Our Daily Bread, “Corrido of the Agrarian Revolution,” Court of the Fiestas, third floor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

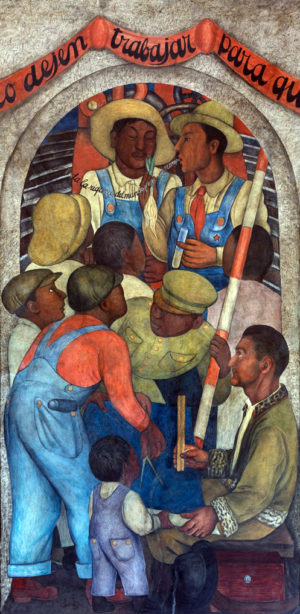

Diego Rivera, We Want to Work, “Corrido of the Agrarian Revolution,” Court of the Fiestas, third floor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This harmony is not present in the scenes in which Rivera caricatures capitalism. In The Capitalist Dinner, figures with grotesque faces sit before a meal of gold coins, with a hungry child crying in the foreground. Behind the capitalists, happy farmers carry a bounty of food, sharpening the contrast between the health of those who value the land and its products and those who exploit it for profit.

Rivera expands on this comparison between capitalism and socialism (or if not yet full socialism, an economic system that values the land and those who work it) in Wall Street Dinner, where he represents rich New Yorkers, such as the magnates John D. Rockefeller, Pierpont Morgan, and Henry Ford feasting on the ticker tape of the stock market. This scene compositionally mirrors Our Daily Bread, which depicts a man (modeled after the socialist governor Felipe Carillo Puerto) wearing the red star of Communism breaking bread before a collective meal. Behind him, the figure of the Tehuana, women from the region of Tehuantepec who became icons of Mexican culture, balances an abundance of fruit upon her head. In these panels, Rivera makes the point that, though the Mexican farmer’s existence is simple, his is true wealth because it comes from a harmony with the land. [3] This is further made explicit in We Want to Work, where Rivera has painted the phrase, “all the wealth in the world comes from the field” in the mouth of a land surveyor.

The “Corrido of the Agrarian Revolution” centers farm workers and scenes of the Mexican countryside, but it also integrates new technology in panels such as The Tractor. The embrace of technology and modernization greatly informs Rivera’s depiction of the international socialist cause in the other corrido, the “Corrido of the Proletarian Revolution.”

Diego Rivera, Distribution of Arms, “Corrido of the Proletarian Revolution” Court of the Fiestas, third floor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Corrido of the Proletarian Revolution

The “Corrido of the Proletarian Revolution” begins with Distribution of Arms, a scene where a woman in red (modeled after the artist’s later wife Frida Kahlo) distributes rifles to revolutionary soldiers at the outbreak of the revolution. Again, the figures in the scene come out beyond the painted architectural border, entering the viewer’s space and incorporating them into the scene, inviting them to take up arms. Also prominent in the foreground are figures modeled after the photographer Tina Modotti and muralist Davíd Alfaro Siqueiros. This inclusion reflects the role that Rivera saw for the artist in distributing ammunition (both literal and metaphorical) to the Mexican people to construct the postrevolutionary society. [4] The lyrics on the ribbon show that this scene, however, is futuristic, reading “And so the proletarian revolution will be. . . .” Here, the Proletarian Revolution is depicted as the eventual successor to Mexico’s recent revolution, reflecting an evolution in Rivera’s politics from a focus on the agrarian revolution in Mexico to an international understanding of political revolution.

Diego Rivera, A Single Front, “Corrido of the Proletarian Revolution,” Court of the Fiestas, third floor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Trip to the USSR

The “Corrido of the Proletarian Revolution” was painted after Rivera’s trip to the Soviet Union in 1927, where he served as the representative of the Mexican Communist Party at the 10th anniversary celebration of the October Revolution. While there, Rivera became more involved in the intricacies of international socialist politics. For example, there was great debate at the time over Josef Stalin’s theory of “socialism in a single country,” in which the Soviet Union turned towards its own national development rather than attempting to initiate further socialist revolutions globally. Rivera, at the time, was aligned with the Trotskyist view that international revolution was necessary to challenge the global dominance of capitalism. Compared to the stairwell and third floor Court of Labor one can see the artist’s political evolution from an emphasis on the Mexican revolution to a view that centers the importance of an international socialist revolution.

After returning from the Soviet Union, Rivera included imagery of Slavic-looking workers and industrial labor, such as in A Single Front, in which a Soviet revolutionary oversees the handshake of a Mexican campesino and a revolutionary soldier. A Single Front can also be read as a response to these debates and divisions within the international Left, with Rivera calling for a united front in the revolutionary cause (formally echoed in the repeated forms of the raised bayonets) while at the same time repeating a theme that is prominent throughout the rest of the cycle (the solidarity between worker and soldier).

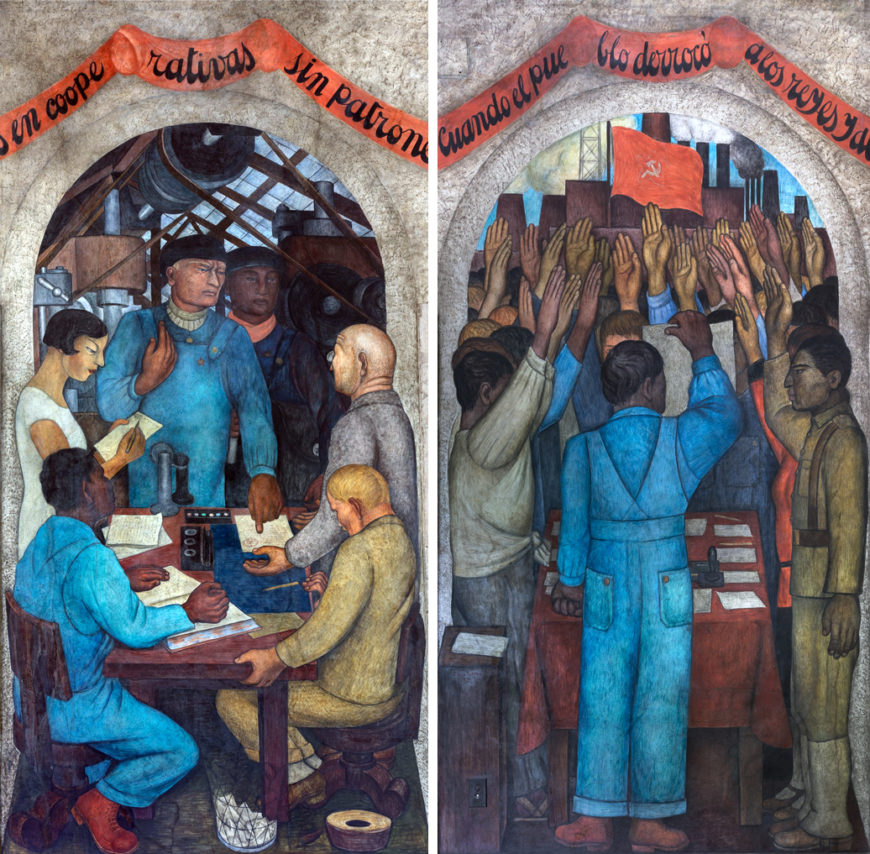

Diego Rivera, The Cooperative (left) and The Protest (right), “Corrido of the Proletarian Revolution,” Court of the Fiestas, third floor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photos: Megan Flattley, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Gustav Klutsis, “Let’s Fulfill the Plan of Great Works,” 1930, lithograph, 118.4 x 83.8 cm (MoMA)

Through his inclusion of industrial factory scenes, Rivera depicted a vision of modernization. He also rendered the socialization of the means of production in The Cooperative, where he imagines a factory owned and controlled by workers.

Another factory can be seen in The Protest, where against a backdrop of a red hammer and sickle flag, an anonymous mass of workers are rendered with their hands raised in solidarity, a motif that would be prominent internationally among artists of the Left, for example, in the photomontages of Gustav Klutsis.

Diego Rivera, the end of “Corrido of the Proletarian Revolution,” Court of the Fiestas, third floor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Artists on the Left

In the “Corrido of the Proletarian Revolution,” Rivera engaged with an international conversation on how art can change the world. While in Moscow, Rivera participated in artist debates over the appropriate form of a revolutionary art, and even signed the manifesto of the artist group October, which included Soviet artists such as Alexander Rodchenko, Sergei Eisenstein, and Alexander Deineka. At a time when many in the Soviet Union were decrying avant-garde artistic forms such as abstraction and montage as “bourgeois” and calling for a realist artistic style, October aimed to incorporate such avant-garde artistic developments into their work created for the masses. Rivera agreed that artists must adapt “the most advanced technical achievements of bourgeois art . . . to the needs of the proletarian revolution.” [5]

An international conversation

Rivera’s mural cycle on the third floor of the SEP referring to the corridos is a critical work that reflects the international conversation of the time surrounding the role and style of revolutionary art. In the stairwell and “Court of Labor” murals, Rivera depicted the decisive position of the revolutionary artist in the collective struggle for a better world. When compared to the corrido cycles in the “Court of Fiestas,” we can see how Rivera’s own view of what that better world looked like was evolving.

While the panels Rivera painted at the SEP before his 1927 trip to the Soviet Union primarily depict Mexico—its industries, celebrations, and people—the corridos cycle in the Court of Fiestas on the third floor reflects Rivera’s new sense of class consciousness, or an awareness of one’s class status and one’s role in the class struggle, across national lines. Rather than exclusively heralding the achievements of the Mexican Revolution, Rivera, and other Communists, began to see it as an initial step towards the achievement of an international socialist revolution, one in which artists wanted to play a contributing role.

Notes:

[1] Diego Rivera, “The revolutionary spirit in modern art,” The Modern Quarterly, volume 6, number 3 (Fall 1932), p. 57.

[2] Rivera (1932), p. 57.

[3] Cynthia Newman Helms, editor, Diego Rivera: a retrospective (New York: Founders Society, Detroit Institute of Arts, in association with W.W. Norton, 1986), p. 246.

[4] Ida Rodríquez Prampolini, Muralismo Mexicano, 1920–1930: Catalogo Razonado I (México, D.F.: Universidad Veracruzana: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2012), p. 243.

[5] Rivera (1932), p. 53.

Additional resources

Alejandro Anreus, Robin Adèle Greely, and Leonard Folgarait, editors, Mexican Muralism: A Critical History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

Jean Charlot, The Mexican Mural Renaissance, 1920–1925 (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1979).

Mary K. Coffey, How a Revolutionary Art Became Official Culture: Murals, Museums, and the Mexican State (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012).

Mary K. Coffey, “All Mexico on a Wall: Diego Rivera’s Murals at the Ministry of Public Education,” Mexican Muralism: A Critical History, edited by Alejandro Anreus, Robin Adele Greeley, and Leonard Folgarait (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), pp. 56–74.

Leonard Folgarait, Mural Painting and Social Revolution in Mexico, 1920–1940: The Art of a New Order (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Laurance P. Hurlburt, The Mexican Muralists in the United States (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1989).

Desmond Rochfort, Mexican Muralists: Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1993).