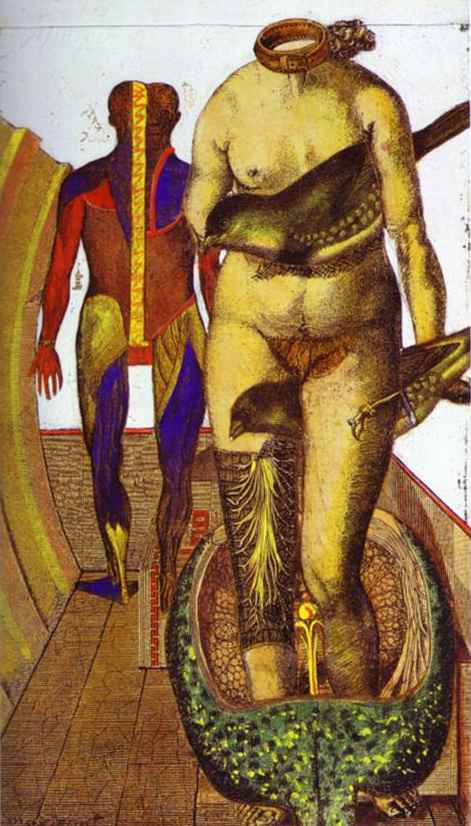

Max Ernst, The Word, or Woman-Bird, 1921, collage with gouache and watercolor, 18.5 x 10.6 cm (private collection)

A nude woman stands in the foreground, a collar around her headless neck and birds tucked between her legs and under her arm. Her right thigh has been skinned to reveal a network of root-like nerves or blood vessels, and she stands knee-deep in what appears to be a cut-open internal organ or organism. Slightly behind her in the shallow space stands a fully-flayed figure that has been sliced vertically in two so we see it half from behind and half from the front

Although some attempt has been made to unify the space by enclosing the figures in a room defined by linear perspective, this work is clearly a collage made up of elements cut from a variety of sources. The foreground woman is Eve from Albrecht Dürer’s Adam and Eve, the background figure is an anatomical illustration, and the birds were presumably sourced from an ornithological guide. The technique of collage, long used in a domestic and craft context to make samplers, scrap-books, and greeting cards, had recently been ushered into the world of fine art by Braque and Picasso’s Synthetic Cubist experiments.

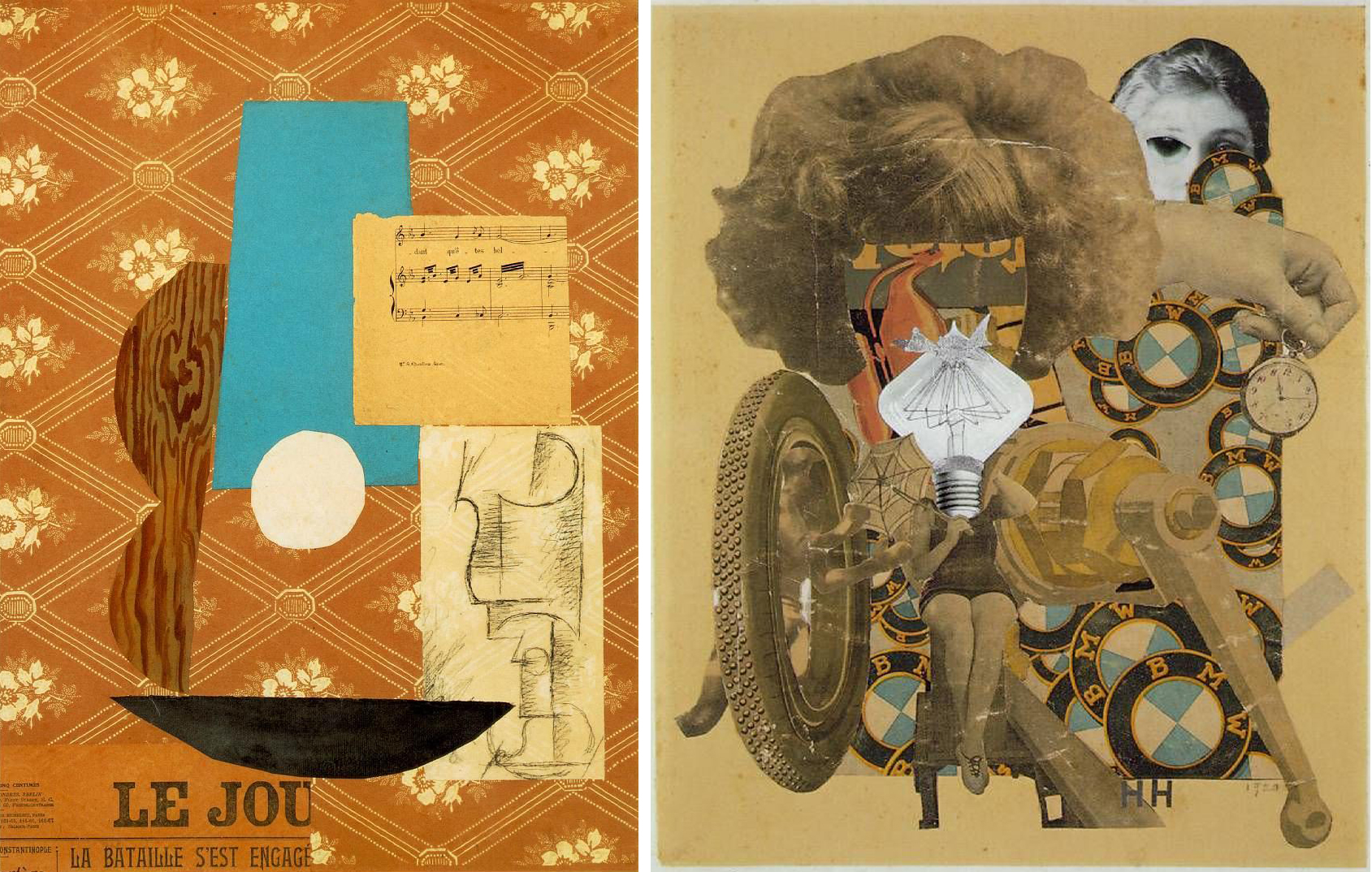

Left: Pablo Picasso, Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass, 1912, collage and charcoal on board, 18 7/8 x 14 3/4 inches (McNay Museum, San Antonio); right: Hannah Höch, The Beautiful Girl, 1919-20, photomontage and collage, 35 x 29 cm (private collection)

The Cubists used collage to further their explorations of the ambiguities of space and representation, but the Dadaists saw in it the potential to advance their absurdist philosophy and political activism.

Inherently Dada

There is something inherently Dada about the technique of collage. Its use of prefabricated or readymade materials negates the importance of artistic skill, and the fact that collage is frequently sourced from mass-produced advertising and journalism collapses boundaries between “high” and “low” culture. Also, the act of making a collage is literally iconoclastic (Greek for “image-breaking”). Cutting up source material implies a rejection of its world-view, a disruption of the way that newspaper, that scientific text, or that advertisement organizes information, and a refusal of the ideas or directives it was intended to convey. Finally, the recombination of these elements gives free play to the artist’s desire to re-shape the world, which for the Dadaists often resulted in images that range from bizarrely humorous to downright disturbing.

Max Ernst, The Word, or Woman-Bird, 1921, collage with gouache and watercolor, 18.5 x 10.6 cm (private collection)

Ernst’s The Word, for example, assaults numerous targets of Dada scorn. Much of the source material appears to be scientific in nature, continuing a broad Dada offensive against science and technology. The incorporation of Dürer’s engraving of Adam and Eve mixes religion with science as well as high art with “mere” illustration. The fact that Dürer’s print uses animal symbolism suggests, but does not spell out, a symbolic meaning for the birds, which had an ambiguous multivalence in Ernst’s art. Their placement here is unquestionably sexual, and Eve’s nudity and the mutilation of both her body and that of the background figure (Adam?) creates uncomfortable overtones of sexual violence. Altogether, the image is absurd, humorous, anti-conventional, and disturbing, all characteristic qualities of Dada.

Photomontage

Dadaists invented a form of collage known as photomontage, which incorporates photographs, sometimes along with other collaged and painted elements. The reputation of photography as a factual record of the world implies a truth-to-reality that can make the absurdity of Dada photomontages additionally disturbing. Many photomontages were sourced from advertisements and journalism. The products and fashions in them appear dated today, but were insistently topical and relevant at the time, and helped Dada to mount an offensive against contemporary social, political, and commercial culture.

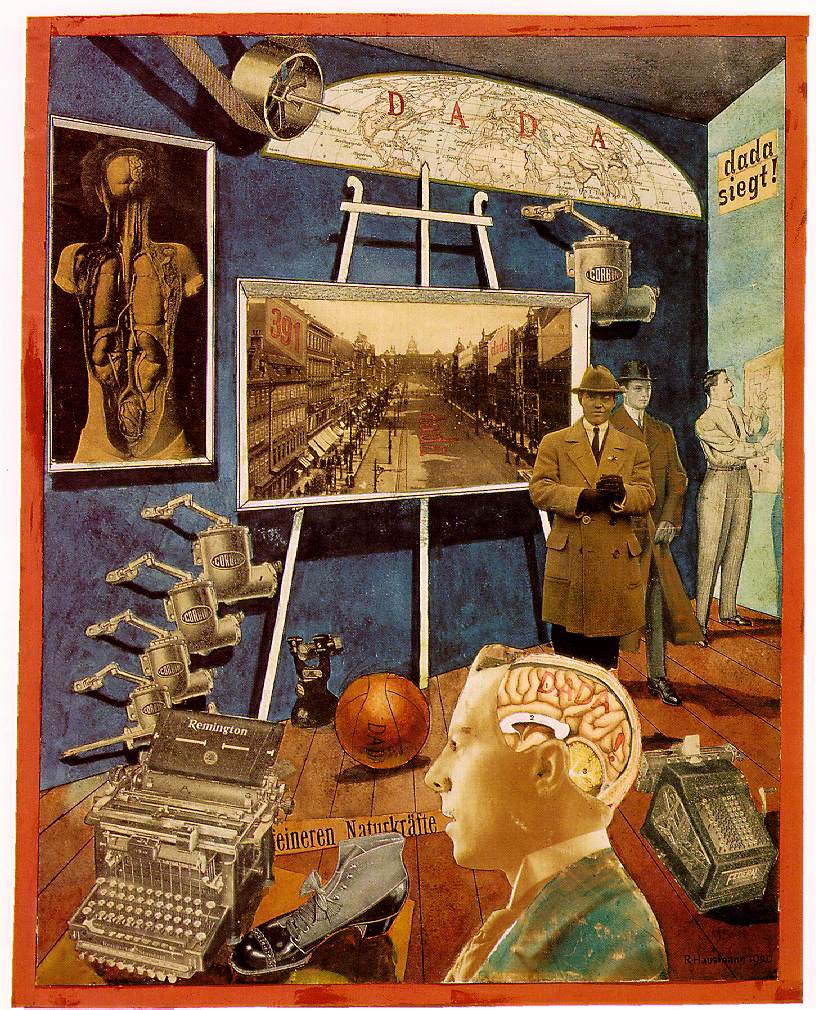

Raoul Hausmann, A Bourgeois Precision Brain Incites a World Movement, also known as Dada siegt (Dada Triumphs), 1920, photomontage and collage with watercolor on paper, 33.5 x 27.5 cm (private collection)

Raoul Hausmann’s photomontage A Bourgeois Precision Brain Incites a World Movement (often called Dada siegt, or “Dada triumphs”) shows an interior cluttered with various objects suggestive of the title: a partial map of the world, a diagram of a brain, and three well-dressed middle-class men, including Hausmann himself. “Precision” is suggested by all of the scientific and machine references, including a typewriter and adding machine in the foreground, as well as another anatomical diagram hanging on the back wall. A pulley and drive belt in the upper left, along with a series of Corbin brand automatic door-closers below, refer to industrial and assembly-line production techniques. The “world movement” of the title is, however, not the orderly, precision phenomenon suggested by these objects. It is instead the unruly disorder of Dada, which we see emblazoned across the map, inscribed on the brain, and written on the street in the background photograph of the Wenzelsplatz in Prague.

Political critique

Hausmann claimed to have appropriated the idea of photomontage from a traditional practice among German military families, who would paste a photograph of their enlisted son’s face over the head of a lithograph of a generic soldier. This anecdote suggests a political dimension to the technique of photomontage, although Dada collages generally challenged militarism and patriotism. Post-World War I Germany was a social and economic disaster. In addition to the destruction of a large part of its industrial base during the war, punitive reparations following Germany’s defeat led to rampant inflation. The generally left-leaning German Dadaists were much more politically active than their counterparts in Zurich, Paris, or New York City, and frequently used art as a form of direct social and political critique.

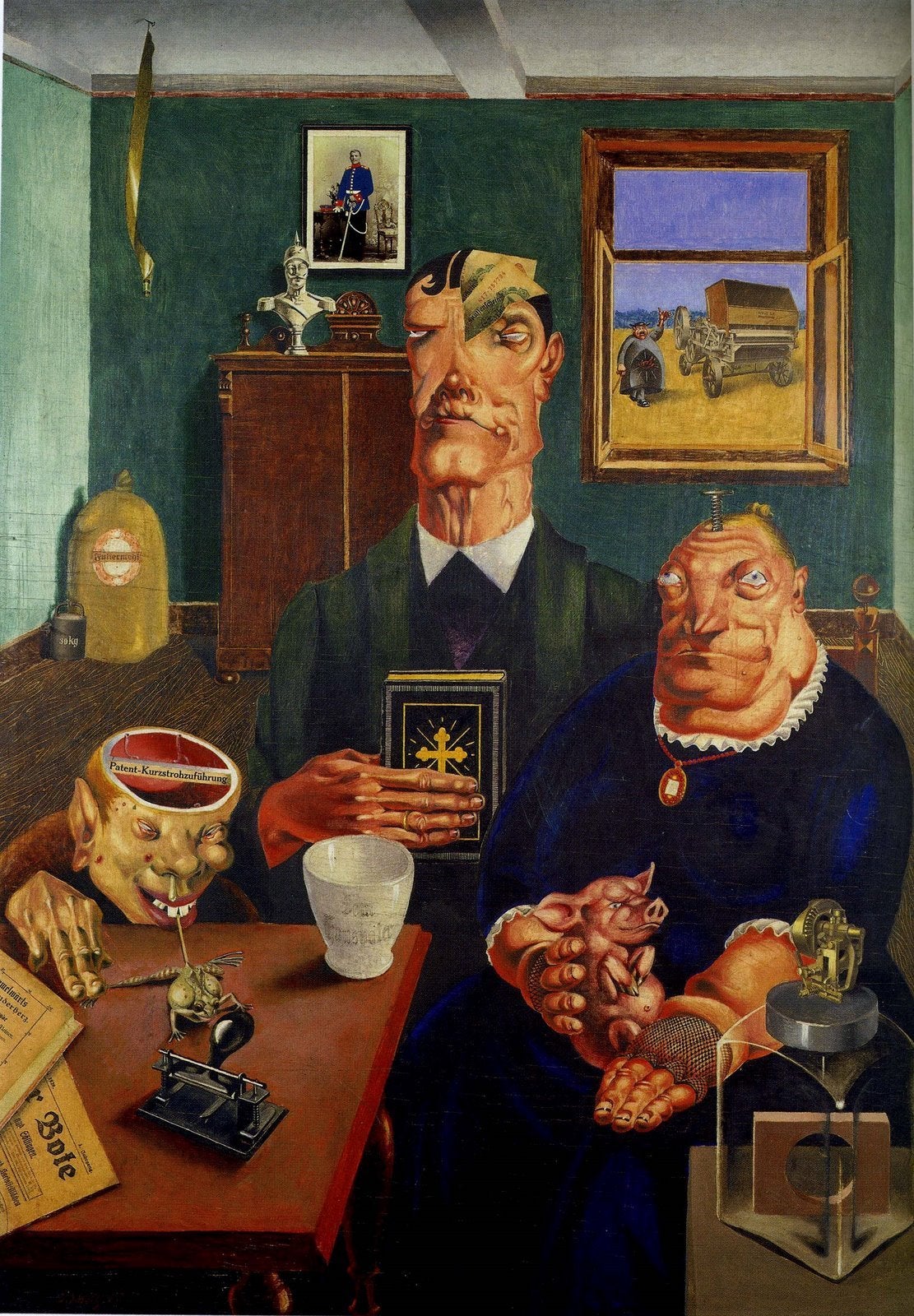

Georg Scholz, Bauernbild (Farmer Picture), also known as Industrial Farmers, 1920, oil on wood with collage and photomontage, 98 x 70 cm (Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal)

Georg Scholz combined collage and photomontage with traditional oil on panel in Bauernbild (Farmer Picture), a scathing satire of the greed and hypocrisy of the large-scale industrial farmers that were replacing traditional small farms. The grotesquely caricatured couple sit proudly in the foreground. He clutches a bible, but his partially sliced open head reveals his true motivation, money. His wife, a nail through her forehead, proudly displays one of her pig-like offspring, while his snotty-nosed and pimple-faced brother is tormenting a toad, a farm-machine patent the only thing in his empty head. Various mechanical devices in the room and a threshing machine out the window demonstrate the family’s devotion to industrialization, while on the back wall, portraits of the recently deposed Kaiser Wilhelm II and another son in uniform demonstrate their patriotic support of the government and the war.

The roots of collage

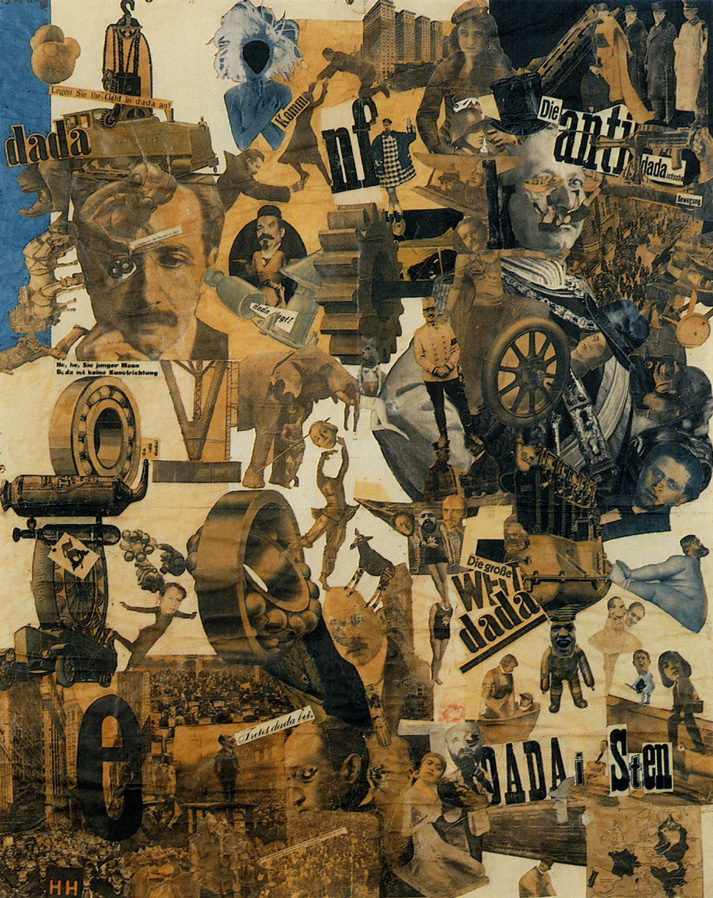

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919-20, photomontage and collage with watercolor, 114 x 90 cm (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie)

With self-conscious irony, Hannah Höch returned collage to its roots as a traditionally female domestic art form. The long title of her photomontage Cut with a Kitchen-Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany suggests how her feminine tool — the kitchen knife that is ostensibly creating the collage — is being used to cut through the (implied masculine) bloated and self-indulgent political class of the time. (Weimar, Germany was where the first democratic constitution of Germany was signed after WWI, giving the name Weimar Republic to the inter-war government.)

Scattered throughout the collage are photographs of German political figures such as the recently-deposed Kaiser Wilhelm II (upper right) and current president Friedrich Ebert (upper center) surrounded by images of gears, ball bearings, soldiers, and other emblems of industrial and military power. Text cut-outs such as “Join Dada” and “invest your money in Dada” exhort us to participate in the mass resistance, represented by crowds of demonstrators in the lower left, along with Communist leaders including Vladimir Lenin and Karl Marx (center right), and recently-assassinated German Communist Party leader Karl Liebknecht (lower left). Interspersed throughout are signs of growing female empowerment. A map in the lower right highlights European countries that had recently given women voting rights, and at the center German Expressionist artist Käthe Köllwitz’s head is juggled by a woman dancer, a common emblem of female freedom in Höch’s work.

The heterogeneity of the source material in all of these examples, along with the dizzying shifts of scale and perspective, makes viewing Dada collages an unsettling aesthetic experience. Because the use of prefabricated, mass-produced source material violates conventions of artistic skill and originality as well as aesthetic harmony, collage was in many ways a perfect medium for Dada iconoclasm and social protest.