Diego Rivera, murals of The Market, Court of Fiestas, north wall, first floor, Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1923–24, Mexico City (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Urban market scenes bustle with activity and seem to burst out of the picture plane. The colorful festivities at the Canal at Santa Anita draw us in with the vibrant colors of their flower vendors. Scenes of industry depict the labor and heroism of the worker. These are but a few of the subjects that cover the walls of Mexico City’s Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP)—the federal government building that houses the Ministry of Public Education. The enormous mural cycle celebrates Mexico: its festivals, its industries, and its people in over 100 panels. After the ten-year revolutionary conflict (1910–1920, which ousted the dictator Porfirio Díaz), the Mexican state sponsored the creation of a mural movement in an effort to express and consolidate a Mexican national culture—in contrast to the previous regime’s adulation of European culture. As writer Carlos Pellicer wrote at the time, with the SEP, “Mexico has begun its Mexicanization.” [1]

The murals were painted from 1923–1928, primarily by Diego Rivera. Many consider the murals to be the foundational work that established the aesthetic of the Mexican Mural Renaissance. The murals address thematic issues of nation-building, indigenísmo, modernization, and socialist politics—themes that Mexican muralists continued to address and that were important in post-revolutionary Mexico.

Revolutionary change

While the panels reflect individual scenes of Mexican life, the theme of the cycle as a whole is revolutionary change in Mexico. As Rivera later wrote “It was my desire to reproduce the pure, basic images of my land. I wanted my paintings to reflect the social life of Mexico as I saw it, and through my vision of the truth to show the masses the outline of the future.” [2] Though the SEP cycle spans three floors, this essay primarily addresses the first floor (and to a lesser extent the second floor), painted between 1923–1924.

Diego Rivera, panels showing Weavers, Dyers, and Tehuanas, Court of Labor, first flour, north wall (or south-facing murals) in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley)

Education in the post-revolutionary context

The SEP cycle was Rivera’s second mural commission after his return to Mexico from Europe where he had lived and studied for 13 years. During his time away, the Mexican Revolution had occurred, after which the Mexican state sponsored cultural works to present a particular image to the world about its stability following ten years of revolutionary conflict. Minister of Education José Vasconcelos wanted to create an aesthetic and educational campaign throughout Mexico to unify the country under a shared cultural heritage. The mural paintings of the colonial missions (where Spanish friars had employed mural paintings to assist in the conversion of Indigenous peoples who often could not read or speak Spanish) were an important model for Vasconcelos as he formulated his vision of a unified Mexico.

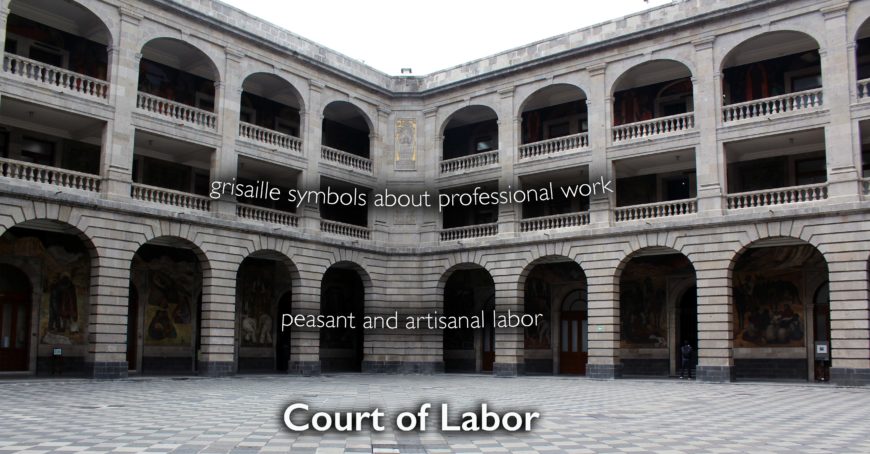

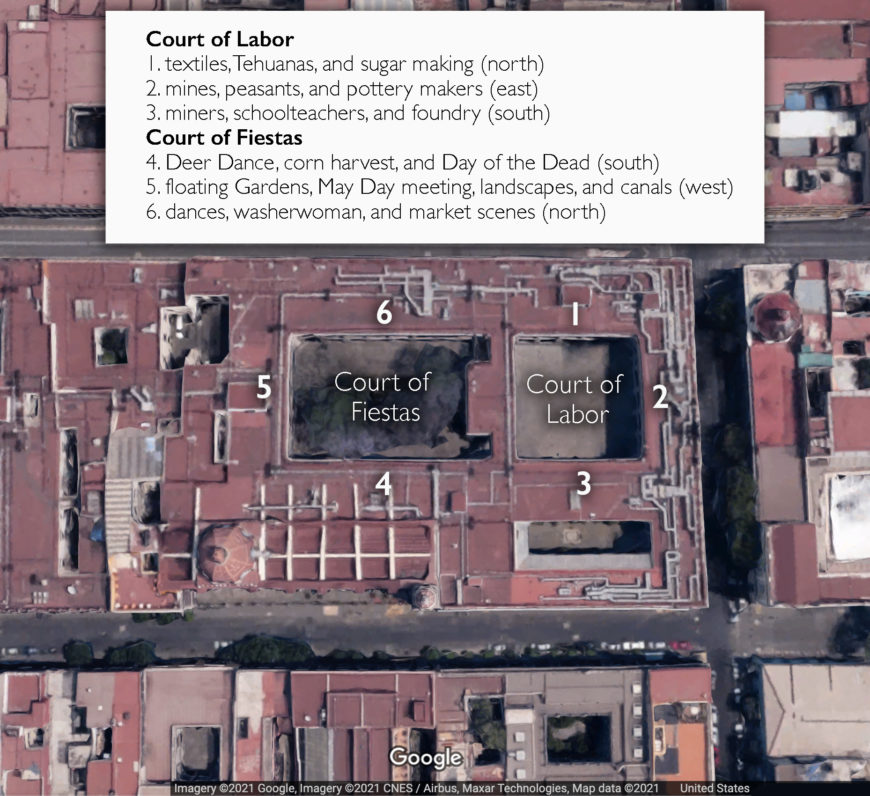

The building

The Secretaría de Educación Publica (SEP) was built originally as the Convento de Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación (Convent of Our Lady of the Incarnation) in 1639 when Mexico was part of the viceroyalty of New Spain until 1821. In 1921, architect Federico Méndez Rivas (with input from Vasconcelos and Rivera), designed renovations and additions to host the new Ministry of Public Education, which oversaw not just education at the national level, but the sponsorship of cultural works and festivals. The three-story building is built around two large open courtyards. The painted walls line a continuous corridor that faces inward towards the courtyards, which Rivera divided thematically as the “Court of Labor” and the “Court of Fiestas.” These thematic divisions inform all three levels of the cycle.

Diego Rivera, Court of Labor, murals in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley)

Due to the constraints of the architectural setting, Rivera designed the scenes to be viewed through the archways that open onto the courtyard, and from various angles as people walk along the corridors. This presented a new challenge for Rivera, whose first mural, Creation (at the National Preparatory School), was executed on a single wall and in encaustic. At the SEP, Rivera had to create an integrated mural cycle that spread across three levels, two courtyards, and nearly 17,000 square feet of wall.

Diagram of the first floor mural program for the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (underlying image © Google)

Fresco technique

Jaguar blowing a conch, c. 1st century, mural from the Palace of the Jaguars, near the Plaza of the Moon, Teotihuacan, Mexico (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Mexican artists had to determine the best manner of painting on walls in response to these commissions. With the SEP cycle, Rivera and the artists Jean Charlot and Xavier Guerrero worked in true fresco (buon fresco, a manner of painting directly on wet plaster, which then dries and becomes part of the wall). Charlot had studied fresco in 15th-century Italian texts such as Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte. Guerrero had also taken frequent trips to the Mexican archeological site of Teotihuacan to study the fresco paintings executed by the Teotihuacanos almost 2,000 years earlier. He claimed to have “discovered” their secret in the use of nopal cactus juice as a binding agent, and this technique was used on several panels in the Court of Fiestas, such as “Dyers.” However, the organic matter deteriorated quickly, and Rivera reverted to a more traditional fresco technique that enabled his monumental work to endure.

Rivera said that at the SEP, he initiated the “true novelty of Mexican painting” in making “the people the heroes of mural painting.” [3] His representation of labor and anonymous workers in a monumental style on the walls of a government building was radical, and reflects his Marxist politics. At the time Rivera was a high-ranking member of the Mexican Communist Party, as well as a founding member of the Syndicate of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors (begun in 1922), reflecting his belief that “the artist is a worker, and unless he expresses his work as a worker, he is not an artist.” [4] Members of the Syndicate also wrote a manifesto in which they repudiated “so-called Salon painting and all the ultra-intellectual salon art of the aristocracy and exalt the monumental expression of art because such art is public property.” The more than 100 panels at SEP embody these ideas.

Diego Rivera, Dyers, 1923–24, first floor, Court of Labor, north wall/south-facing mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley)

Court of Labor

In the Court of Labor, Rivera represented traditional economic activities such as mining and sugar harvesting. These industries had been prevalent in Mexico throughout the colonial period (prior to the revolution), and were largely controlled by foreign interests. Rivera organized his painted scenes of labor to reflect the Mexican regions where they took place. The south-facing wall depicts the weavers and dyers from Tehuantepec and the sugar cane harvesting that occurred in Yucatán (both southern regions). The northern region of Mexico is represented on the opposite wall by workers at steel foundries, as well as farmers and a rural school teacher. The west-facing wall panels depict mining, farming, and the creation of pottery that occurred primarily in the western region of Jalisco.

Diego Rivera, Entrance to the Mine, 1923–24, first floor, Court of Labor, east wall/west-facing mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Garrett Ziegler, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In Entrance into the Mine (on the west-facing wall) workers carry lumber, shovels, and pickaxes as they descend into the opening of the mine. The mine’s arches suggest eyebrows and its opening a mouth that allude to the Mexica (Aztec) “earth monster” deity Tlaltecuhtli who is often depicted with a gaping mouth and crocodile skin, and who represented the surface of the earth. According to Mexica mythology, Tlaltecuhtli demanded human blood for nourishment—a debt owed because the gods had created life. By showing the workers disappearing beneath the surface of the earth, Rivera suggests that they are the new sacrifice.

Diego Rivera, Leaving the Mine, 1923–24, first floor, Court of Labor, east wall/west-facing mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley)

The next panel Leaving the Mine provides another visual evocation of sacrifice by alluding to depictions of the Christian martyr Jesus Christ. This scene depicts a worker being searched upon exiting the mine at the end of his work day. He is cloaked in white and with his extended arms resemble the crucified Christ. In these two scenes, Rivera has made clear that capitalism requires the continual sacrifice of workers.

Diego Rivera, The Liberation of the Peon, 1923–24, first floor, Court of Labor, south wall mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Kgv88, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Lamentation. Giotto, Scrovegni Chapel, 1305–06, Padua, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In one of the most recognizable scenes from the cycle in the Court of Labor, The Liberation of the Peon, Rivera once again draws on imagery of Christ’s martyrdom. Here he links the worker (a farmer) to the martyred form of Christ as a way of glorifying him.

These evocations of Christ demonstrate Rivera’s recent study of early Italian renaissance fresco painting, particularly Giotto’s Arena Chapel. For The Liberation of the Peon, he borrows from the scene of the Lamentation in the Arena chapel. There were precedents for the contemporary use of Christian iconography in earlier murals at the National Preparatory School and even earlier in the colonial mural tradition that focused on religious narratives.

Diego Rivera, Symbol of Farming, second floor, Court of Labor, mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank)

As the Court of Labor proceeds upwards, the second floor features twenty symbolic representations of intellectual work in the sciences and the arts executed in grisaille to emulate architectural bas-relief. The representation of intellectual work on the second floor builds on the base of labor that Rivera depicted on the ground floor, formally establishing that the work of everyday laborers forms the foundation for the successes of the post-revolutionary state.

Diego Rivera, Court of Fiestas, 1923–24, first floor, south wall murals in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: FlyingCrimsonPig, CC BY 2.0)

Court of Fiestas

While the Court of Labor draws heavily on renaissance imagery, the first floor of the Court of Fiestas looks to Indigenous (specifically, pre-Columbian) and popular forms. In Fiesta del Maíz, the influence of Mexica stone sculpture can be seen in the way that a man and corn seem unified into a single form, aligning the farmer with the grain.

Diego Rivera, Fiesta del maíz, 1923–24, first floor, Court of Fiestas, south wall murals in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Megan Flattley)

Maize Deity (Chicomecoatl), Mexica culture, 15th–early 16th century, basalt, 35.6 x 18.1 x 8.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This formally echoes stone sculptures of the Mexica maize deity Chicomecoatl, who is often depicted frontally with maize and a blocky headdress that grants the sculpture a rectangular shape that is echoed in the shape of the farmer with maize on his back. An emphasis on the pre-Columbian heritage of the nation was important in the post-revolutionary moment, as the Mexican state sought to promote a new national identity that was not rooted in the imitation of European art forms. Archaeological excavations unearthed new sites and objects. Upon his return to Mexico, Rivera took a state-sponsored tour of the southern region, including stops at the Maya site of Chichén Itzá and the isthmus of Tehuantepec. Rivera described this tour as producing “an esthetic exhilaration which it is impossible to describe.” [5] He called Mexico “the very center of the plastic world” and attributes his artistic maturation to his discovery of the natural beauty of his homeland. [6]

Diego Rivera, Court of Fiestas, with panels showing day of the Dead, first floor, south wall murals in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Diego Rivera, Dance of the Deer (detail), first floor, Court of Fiestas, south wall mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City

Like the Court of Labor, the direction of the walls informs the regional celebrations displayed. On the first floor, the Tehuanas (women from Tehuantepec) are a prominent motif of the south-facing wall. Various festivals and celebrations are depicted, including the Mexican holiday Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), the floating gardens at Xochimilco, and dances such as the Dance of the Deer and La Zandunga. Rivera locates the origin of the revolutionary spirit of the Mexican people in these unique celebrations.

Rivera dedicated a number of panels to Día de los Muertos, a Mexican holiday that honors those who have died and reflects the mixing of Catholic and Indigenous religious practice.

Diego Rivera, Day of the Dead—City Fiesta (detail), Court of Fiestas, south wall mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City

In Day of the Dead—City Fiesta, Rivera represents a worker, a farmer, and a soldier (the triumvirate of revolutionary heroes) in three puppet calavera figures with guitars (a Mexican artistic representation of a skeleton inspired by late 19th-century printmaker José Guadalupe Posada). For Rivera and others, when the worker, farmer, and soldier united, they would continue the project of the Mexican Revolution—here Rivera ties the scenes of celebration of this holiday back to the political context of a post-revolutionary Mexico. Rivera included a self-portrait in the crowded street scene. He looks out at the viewer, from amidst the various classes of people represented, indicating his role as observer.

Diego Rivera, The Market, first floor, Court of Fiestas, north wall mural in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City (photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

We see the impact of Rivera’s earlier Cubist training in these images. In the panel titled The Market, Rivera represents a busy urban scene through a crowded, compressed composition. The repeated forms of the many sombreros recalls the Cubist technique of stacking geometric forms. The Market reflects how Rivera adapted this Cubist training to create large-scale, architecturally integrated paintings.

Jean Charlot and Amado de la Cueva, left: escutcheons of the states of Mexico (photo: Kvg88, CC BY-SA 3.0); center: escutcheon of the state of Mexico (photo: Kvg88, CC BY-SA 3.0); right: escutcheon of the state of Campeche (photo: Kvg88, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Syndicate

We also find on the second floor of the Court of Fiestas the escutcheons of the states of Mexico painted by Jean Charlot, Amado de la Cueva, and other members of the Syndicate of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors. The SEP mural commission was originally to be completed by multiple artists. An important tenet of Mexican muralism was the advocacy of a collective artistic production and reception. However, despite his membership in the Syndicate, Rivera eventually managed to secure the entire commission for himself and had panels painted by Charlot and others torn down. He claimed that the difficult task of creating a unified aesthetic work could not be completed by artists who had individual styles. Only four main panels painted by Charlot and Amado de la Cueva remain today.

Embracing Mexican culture

The first and second floors of the SEP mural cycle reflected the post-revolutionary government’s embrace of uniquely Mexican culture and popular traditions, and served as a critical origin site for Mexican Muralism. At the SEP, Rivera and others developed a true fresco painting method, a narrative of national regeneration, and a new aesthetic. The SEP murals also reflected the muralists’ embrace of socialist politics that glorified the worker. These views evolved over the course of the five years that Rivera painted at the SEP.