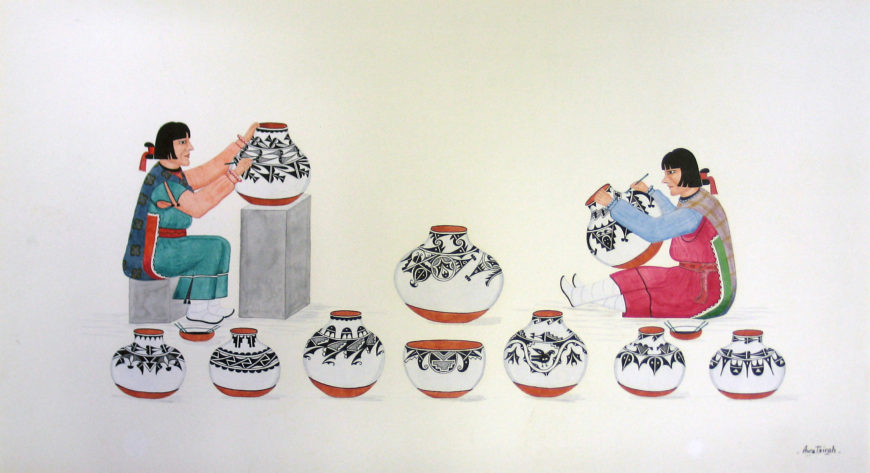

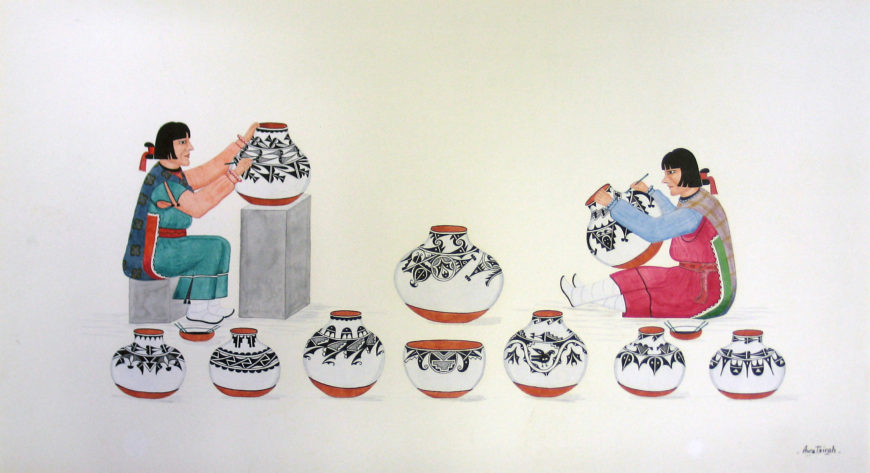

Awa Tsireh, Pottery Makers, c. 1930, ink and watercolor, 33.02 x 54.29 cm (Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio)

Two Pueblo women sit and decorate pottery with brushes made of yucca leaves. Beside them, finished vessels in white, black, and red are arranged in a horizontal line. Except for delicate shadows cast on the right side of the women and vessels, the background is left blank and we do not know where these women are working. This painting, known as Pottery Makers, is one of many that the artist Awa Tsireh (Cattail Bird, Spanish name Alfonso Roybal) created about Pueblo cultures, including images of ceremonial dances and pottery designs. The Pueblo people are one of many Native American cultural groups living in the southwestern United States.

Increasing contact

Awa Tsireh was a painter and metalsmith from San Ildefonso Pueblo, a Tewa-speaking Indigenous group in New Mexico. Awa Tsireh (and other contemporaneous Pueblo artists) used commercial artistic media, such as ink and watercolor, and their paintings were sold to primarily non-Native audiences. As the result of Pueblo communities’ increased contact with U.S. settler-colonial society in the first decades of the twentieth century, Pueblo pottery and Pueblo paintings depicting pottery-making scenes attracted urban middle- and upper-middle-class white audiences (mostly from the urban East coast) some of whom felt that mainstream U.S. culture had lost its harmonious balance between nature and civilization. Other Pueblo painters such as Ma-Pe-Wi (Velino Shije Herrera, Zia Pueblo) and Quah Ah (Tonita Peña, a San Ildefonso female painter who lived in Cochiti Pueblo) also produced paintings of the same subject matter. Pottery Makers demonstrates how Awa Tsireh’s interactions with an emerging community of non-Native cultural elites (including artists, writers, philanthropists, art collectors, and scholars) living in or visiting Santa Fe and Taos in New Mexico shaped how he depicted scenes of Pueblo pottery making.

Art and ethnography

In the late 1910s, non-Native cultural elites in Santa Fe, such as Edgar Lee Hewett, founder of the Museum of New Mexico (MNM), and Elizabeth DeHuff, wife of then superintendent of the Santa Fe Indian School began to recognize Pueblo paintings not only as ethnographic documents that described Pueblo ceremonial dances and life at villages, but also as fine art. Early advocates of Pueblo paintings encouraged artists to create art based on their own cultures. However, this does not mean Awa Tsireh passively produced ethnographic depictions of Pueblo culture at the behest of white anthropologists. It is important to emphasize that Pueblo artists like Awa Tsireh had room for negotiation and artistic ingenuity, such as we see in Pottery Makers.

Awa Tsireh, Pottery Makers (detail), c. 1930, ink and watercolor, 33.02 x 54.29 cm (Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio)

The pottery in the painting

Unidentified San Ildefonso artist, Jar, c. 1890s, clay and paint , 31.75 cm in diameter (Denver Art Museum)

All but one of the vessels in Pottery Makers are globular in shape with a short neck. They look like actual vessels made with black designs on white slip (watery clay paint) and a red band at the bottom as well as on the inside below the rim. Their color palette resembles black-on-cream wares from the late nineteenth century, such as a storage jar made in the 1890s that uses only black color for abstract motifs on the white field and has an undecorated red band at the bottom and on the rim.

Unknown San Ildefonso Artist, Jar, c. 1900 (courtesy of School for Advanced Research; photo: Lynn Lown)

However, by the turn of the twentieth century, black-on-cream ware was gradually replaced by new styles, such as polychrome ware that showed colorful abstract motifs using reddish brown pigments.

By the time Awa Tsireh produced this painting around 1930, Julian and Maria Martinez had achieved national success with their now iconic monochrome black-on-black polished ware. Importantly, the ceramic style depicted in Pottery Makers does not follow the trend at San Ildefonso Pueblo at that time, which means that Awa Tsireh’s paintings are not exact depictions of life in San Ildefonso Pueblo—despite his use of a naturalistic approach. The artist’s choice to use this style of pottery helps us to understand the complex thought process of a Pueblo artist in the early twentieth century.

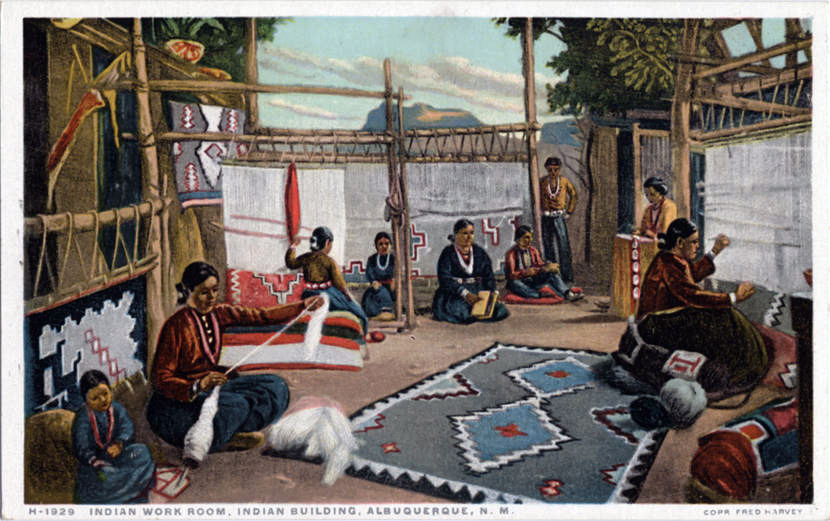

“Indian work room, Indian Building, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Navaho Indians among them Elle, the most famous weaver among the Navahos, and Tom of Ganado, her husband, and Indians from other tribes—Santo Domingo, Isleta, Laguna, and San Felipi,” a postcard from the Fred Harvey series, c. 1900–09 (Newberry Library)

The significant stylistic change from black-on-cream wares in San Ildefonso pottery around the turn of the twentieth century, and the invention of polished black-on-black wares in the late 1910s, were the result of Pueblo communities’ increased contact with U.S. settler-colonial society. As the result of railroad tourism in the American Southwest from the 1890s, Pueblo pottery became widely popular among white urban middle- and upper-middle-class individuals. Along with the railroad run by Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe (AT & SF) Railway, Fred Harvey Company’s hotels sold Indigenous hand-made objects and set up demonstrations of ceremonial dances as well as the making of Indigenous arts like Pueblo pottery and Diné (Navajo) weavings.

Sales

Meanwhile, Pueblo communities needed to earn cash due to the reduction of the land available for agriculture and hunting due to the encroachment of Anglo and Hispanic ranchers seeking to increase their production of beef as well as the increased presence of a cash economy after New Mexico was annexed by the U.S. in 1848 as a result of the Mexican-American War. The sales of Indigenous hand-made objects for the non-Native market helped Pueblos to survive economically. These sales also created room for Pueblo cultural expression in the face of the forced assimilation policy by the U.S. federal government, which included sending Pueblo youths to boarding schools as well as attacks against ceremonial practices that culminated in a series of documents issued in the early 1920s (by Commissioner of the Office of Indian Affairs Charles Burke) restricting many of them.

At this time, Pueblo potters—mostly women—began to produce less elaborate small pottery vessels and figurines so that they could maximize their sales to tourists. Early tourists preferred small inexpensive vessels as souvenirs and cared less about quality. At the same time, Pueblo potters began to experiment with non-conventional shapes and designs (such as ashtrays, vases with handles, or figurines). They also created pseudo-ceremonial vessels that appealed to tourists’ and anthropologists’ curiosity about Indigenous esoteric materials, despite the fact that they had no ceremonial function within the Pueblo communities, and were a tactic to protect ceremonial objects from outsiders.

Questions of authenticity

Not all of these changes in the production of Pueblo pottery were favorable in the eyes of white cultural elites who were concerned about the impact of tourism and assimilation policies on Pueblo cultural traditions. Some were concerned that changes to these objects made them less “authentic,” a perception that was shaped by the myth of a vanishing race—a pervasive assumption among non-Natives that Indigenous peoples and their cultural distinctiveness would completely disappear in the face of modernization and settler-colonial practices. Herbert J. Spinden, a curator at the American Museum of Natural History, praised San Ildefonso pottery as “decorative art” while expressing his concerns over the destructive impact of “the commercializing American contact” on “the remains of the native culture.” [1] In collectors’ and scholars’ imaginations, Native traditions were on the verge of extinction.

While museums tried to collect what they regarded as pottery vessels free from the negative impact of tourism, Kenneth Chapman, curator of the MNM, encouraged Pueblo potters to study older vessels to revive earlier traditions. Awa Tsireh referenced black-on-cream wares for Pottery Makers—the style widely used in San Ildefonso Pueblo before the expansion of tourism in the Southwest that had caused radical changes in Pueblo pottery-making—and was surely aware of the special value attached to older vessels by educated non-Native audiences.

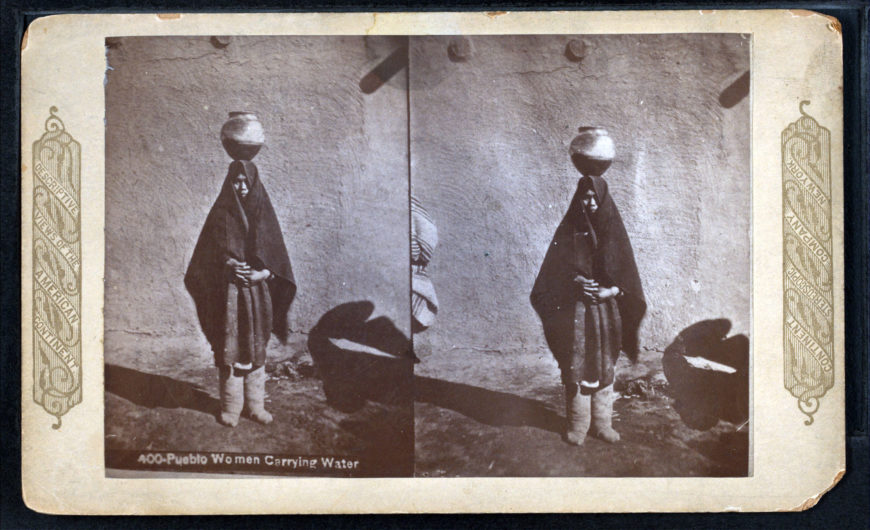

Photographs showing the “olla maiden trope” were common in the late 19th-century U.S. Pueblo Women Carrying Water, c. 1870–98, from Stereoscopic views of the Indians of New Mexico, c. 1870–1908, albumen photoprint (The New York Public Library)

Women in the painting

Interestingly, Awa Tsireh’s pottery-making scenes rarely include male figures (even though pottery-making is traditionally women’s work among Pueblo people, men also participated in the production of pottery—and the artist himself decorated vessels). Representations of Pueblo women carrying an olla on their head (“olla” is a Spanish word meaning “cooking pot” but often used as “water jar” in this context) were ubiquitous in dominant U.S. visual culture including in photographs, advertisements, and artworks.

The trope of the “olla maiden” is a romanticized image of Pueblo culture, especially women. White intellectuals in the late nineteenth century saw over-packed urban spaces and machine-made commodities as causing human alienation as well as physical and moral degeneration (especially among white males). The olla maiden became a symbol of an attempt to restore what they felt had been lost: a harmonious balance between nature and civilization. For them, traditional Native handmade objects made by women from natural materials, such as basketry and pottery vessels, provided symbolic connections to nature and a romanticized past. In his pottery-making scenes, Awa Tsireh aligned his pottery-making scenes with the popular “olla maiden” trope by showing only women and adding more globular-shaped jars that referred to earlier types of vessels rather than a diversity of vessels including plates, different types of bowls, canteens, and so forth.

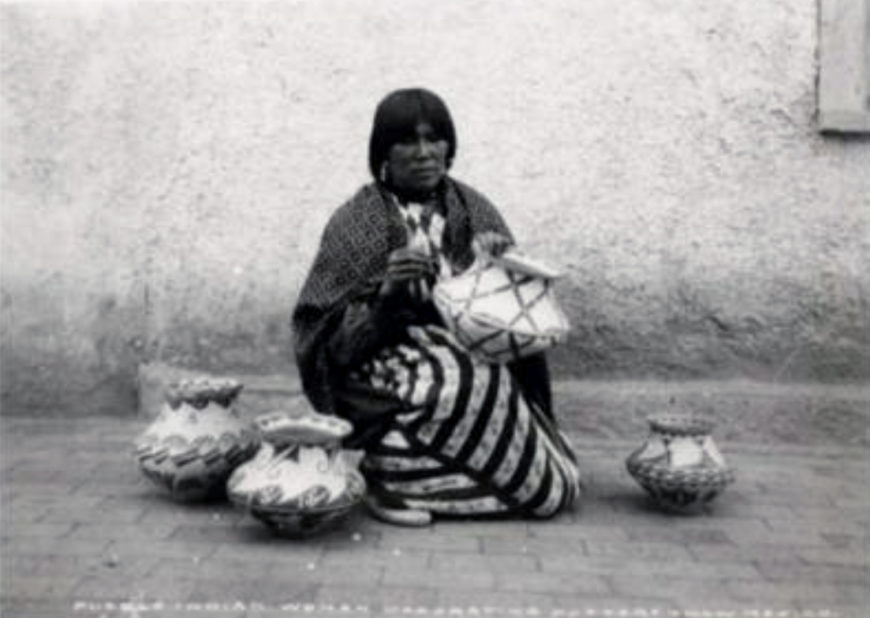

Photographer unknown, Dolorita Vigil: Dressmaker and Potter, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico, c. 1915 (Palace of the Governors Photo Archives Collection)

Awa Tsireh’s pottery-making scenes reference an even more specific variation of the “olla maiden” trope—images of Pueblo women making pottery. A staged photograph that shows this subject includes Dolorita Vigil, from San Ildefonso; she squats on her heels, holds a water jar, and is surrounded by three other water jars. She holds a brush made out of a yucca leaf in her right hand as if she is decorating the jar. The brick-paved ground and the wall behind her suggest that she is probably in the courtyard of the Palace of Governors in Santa Fe where Kenneth Chapman had invited San Ildefonso potters to perform demonstrations for white middle- and upper-middle-class visitors.

This staged photograph derives from popular demonstrations of Indigenous art being made at tourist sites. Tourist interest in these hand-made objects was so great that they sought to observe ceramic production by the hands of Indigenous artists. The artificiality of this photograph’s setting reveals that the focus was on reproducing images of a Pueblo woman with her water jar, even if it was outside the Pueblo context. Awa Tsireh was surely aware that the “olla maiden” trope provided a frame of reference to strengthen the notion of “authenticity” projected onto Pueblo pottery.

Documenting production

Although photographers had produced images of Pueblo pottery-making since the late nineteenth century, a renewed interest in documenting production emerged in the early decades of the twentieth century. Non-Native specialists studied techniques and design principles for different types of pottery as a way of establishing criteria to discern the quality of Pueblo pottery. They believed this could help to elevate the status of Pueblo pottery to fine art.

Illustration of the Pueblo pottery arranged according to what was considered “good” (the row on top) and “bad” (the bottom row) by collectors. from Olive W. Wilson, “The Survival of an Ancient Art,” Art & Archaeology (January 1920): 28.

An essay in Art and Archaeology by Olive Wilson, “The Survival of an Ancient Art” (1920) illustrated the processes of pottery-making with photographs and text. It also includes a photograph showing Pueblo pottery arranged horizontally, similar to what we see in Awa Tsireh’s Pottery Makers—he was likely referencing this type of photographic representation of Pueblo culture. The photograph in Wilson’s essay contrasts what the author regarded as “good” pottery on the top row (namely globular-shaped jars with refined shapes and meticulous details and a traditional rectangular corn-meal bowl) and “bad” pottery on the row below (here there are types of vessels invented and sold for tourists, such as clay figurines and non-conventional-shaped vessels decorated with less elaborate designs).

This photograph also shows pottery vessels from a consistent angle, and arranges them isolated from the surrounding environment. This type of neatly arranged photographic image resonated with emerging research on designs of Indigenous artifacts. It shows a marked difference from the cluttered souvenirs commonly found in home decoration that became widely popular among US white middle- and upper-middle classes around the turn of the twentieth century. A trend where Indigenous artifacts from different cultures were promiscuously displayed among artworks and books about Indigenous peoples in dens, alcoves, and hallways. This fashion became possible when department stores and world fairs brought Indigenous art to their clientele, and reflected the value that Indigenous hand-made objects had for some urban white elites. Displays at “Indian corners” framed Indigenous hand-made objects as “souvenirs” and “curios” rather than as “fine arts” or “ethnographic specimens.”

The photographic representation of Pueblo pottery employed by anthropologists and curators, could dictate to viewers how these wares should be viewed and what constituted “good” or “bad” pottery as “fine art.” Awa Tsireh drew on the authority tied to this photographic format for Indigenous work, in part, perhaps, because of its appeal to white audiences.

Awa Tsireh, Pottery Makers, c. 1930, ink and watercolor, 33.02 x 54.29 cm (Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio)

Unique representations

Awa Tsireh’s choice to incorporate older styles into his painting may have resonated with his predominantly white, educated, non-Native audiences, who had access to books and articles about Pueblo pottery. He chose to appeal to their particular interest in older vessels from the late nineteenth century rather than those produced by contemporary potters. Awa Tsireh’s Pottery Makers tacitly confirms his non-Native audience’s understanding of ideally good Pueblo pottery, and gives his painting an aura of authenticity that would have appealed to his audience. Meanwhile, the artist reinforced his audiences’ romanticized image of Pueblo culture by referencing the “olla maiden” trope. Because of decades of interactions with non-Native intellectuals, artists at San Ildefonso Pueblo—like Awa Tsireh—were aware of the interest in describing Native techniques and analyzing designs.

Pottery Makers demonstrates that Awa Tsireh created his own unique representation of Pueblo women and pottery by integrating different modes of representations of Pueblo people and culture found in settler-colonial U.S. visual culture into his pottery-making scenes. These ranged from the popular “olla maiden” trope to anthropological photographs studying pottery design. By aligning his artworks with his audiences’ desire for authenticity, Awa Tsireh found a means to solidify his external reputation as an outstanding Pueblo artist. At the same time, Awa Tsireh visualized his understanding of contemporary Pueblo communities interacting with outsiders (tourists and anthropologists alike). This created a complex dynamic where his own culture was Othered by the very outsiders he references in his artwork. In this way, Awa Tsireh disrupted the uneven power relationship between the colonizer as observer, and the colonized peoples as the observed.

*At the beginning of this project, the author consulted with the Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) of San Ildefonso Pueblo in order to make sure another essay did not violate protocols of religious matter from the perspectives of cultural specialists. Out of respect to the decision made by the board member, the author decided to write about this topic instead of the original plan. I express my gratitude to the members of the advisory board who reviewed my proposal, and Mike Bremer, officer of THPO. Western academic institutions have tended to regard Indigenous communities as the subject of research and excluded from the decision-making processes related to research projects. Tribal consultation is an important approach to redress structural problems of academic research about Indigenous cultures. Although just a consultation is not enough to redesign research to better reflect interests of Indigenous communities, this essay seeks to introduce such issues to a broader public by using a platform like Smarthistory.

Notes:

[1] Spinden discussed this in his article “The Making of Pottery at San Ildefonso” (1911)

Additional resources:

Babcock, Barbara A. “Pueblo Cultural Bodies.” The Journal of American Folklore 107, no. 423 (Winter 1994): pp. 40–54.

Bernstein, Bruce. Santa Fe Indian Market: A History of Native Arts and the Marketplace. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2012.

Brody, J.J. Pueblo Indian Painting: Tradition and Modernism in New Mexico, 1900–1930. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 1997.

Hutchinson, Elizabeth. The Indian Craze: Primitivism, Modernism, and Transculturation in American Art, 1890–1915. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2009.

Scott, Sascha. “Awa Tsireh and the Art of Subtle Resistance.” The Art Bulletin 95, no. 4 (2013): 597–622.