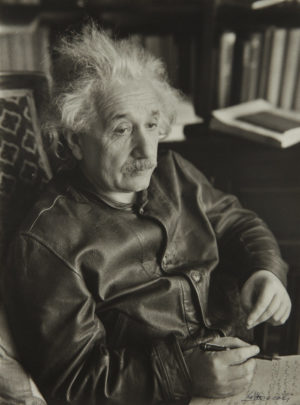

A portrait of Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein wears a leather jacket and sits in a tall-backed upholstered chair. His hand loosely holds a fountain pen suspended over ink-layered pages. His heavy-lidded, faraway gaze is soft, pensively disconnected from both his writing and the photographer who is observing him. He appears entirely lost in thought. The focus is also a bit soft, which renders Einstein’s immediately recognizable, almost electrified tufts of white hair even softer. The leather jacket picks up the ambient light from an unseen window and its myriad folds envelop the thinker’s arms and buttoned-up upper body. The leather jacket, which became a stylish, edgy fashion accessory for men in the late 1930s, seems “off-brand” for Einstein. The jacket calls attention to his body—perhaps strange for someone so celebrated for his mind. Einstein looks comfortable, casual, and somewhat fragile in this delicate portrait.

Lotte Jacobi took this photograph of the theoretical physicist Albert Einstein, at his home in Princeton, New Jersey (at the time he was a professor at the university). Both Jewish, the two had been family friends a decade earlier in Germany. Einstein had renounced his German citizenship for political reasons after leaving Nazi Germany in 1933, and Jacobi had been forced to emigrate to the United States from Nazi Germany after she too renounced her German citizenship in 1935. She also settled on the East Coast, but in New York City—not too far from Einstein in Princeton.

Jacobi and Einstein collaborated on the crafting of his media image in a series of late-1930s Princeton portraits commissioned by Life magazine. Einstein agreed to sit for the photo session only if Lotte Jacobi was assigned to photograph him. [1] The image of Einstein in a leather jacket is unusual in that it catches him in a less-guarded, less-constructed moment than the others and offers the viewer a glimpse of the world-famous theoretical physicist as an individual, rather than as a stereotyped professor.

Lotte Jacobi, Albert Einstein standing at his Piano, 1938 (negative); 1978 (print), halftone print, 17.8 × 12.7 cm (Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University)

More formal portraits

Jacobi’s portrait Albert Einstein standing at his Piano, from the same session, conveys a more expected portrait of an intellectual: standing, hand on a shining clean surface, holding a pipe (not smoking it), in front of a bookcase filled with orderly bound volumes. His gaze is focused on the camera’s lens so that he appears to look at the viewer. He is posing for the camera to convey intellectual dignity. Besides the portrait of Einstein in the leather jacket, Jacobi’s other photographs from 1938 include at least two in which Einstein is wearing a three-piece suit, holding a pipe, making eye contact with the viewer, and looking professorial. These photographs project a carefully crafted image of a scholarly man.

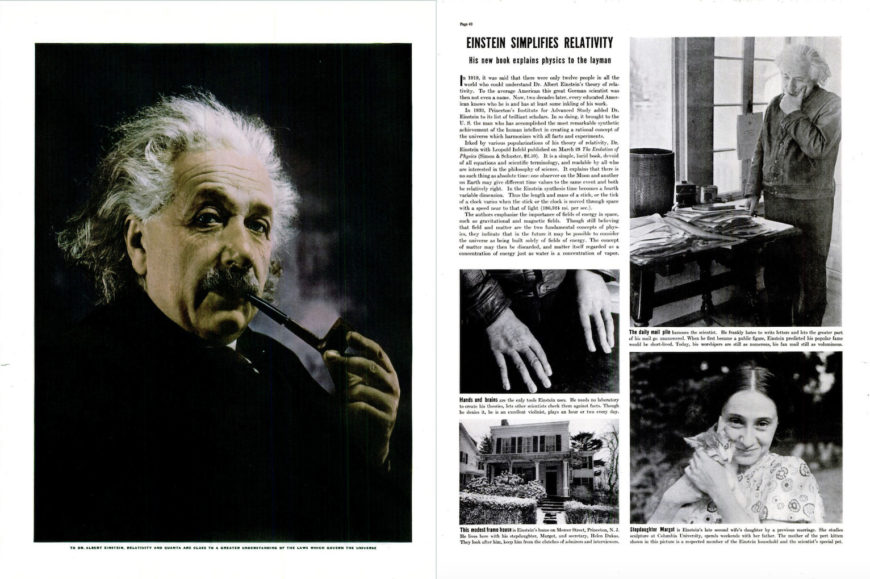

The full-page lead image for the two page article on page 48 of the April 11, 1938 number of Life was a head-and-shoulders color studio portrait of Einstein wearing a dark suit with a pipe in his mouth, looking directly into the camera, taken by Gösta P. G. Ljungdahl (who is honored with a portrait and a brief bio on p. 61 of the magazine). Einstein’s The Evolution of General Physics, a general audience introduction to his theory of relativity, had just been published.

The full-page lead image for the two page article on page 48 and 49 of the April 11, 1938, Life Magazine

Lotte Jacobi contributed three black and white photographs to the spread on page 49: a close-up of Einstein’s hands resting on a cleared surface, in which we glimpse his leather jacket, a portrait of his house exterior in New Jersey, and an image of Einstein in his leather jacket, grasping his chin with a world-weary expression, standing over a pile of unopened mail. The caption for the last image states: “The daily mail pile harasses the scientist.” For Life magazine’s editors, Einstein’s disorderly home milieu and leather jacket attire were acceptable as long as there was a specific focus on the daily deluge of correspondence. Jacobi’s photograph of Einstein’s hands was captioned “Hands and brains are the only tools Einstein uses” with the photograph reinforcing the labor of his hands rather than the time he spent thinking. Jacobi’s portrait of Einstein as lost in contemplation and seemingly unaware of the camera was deemed an undignified portrayal. [2]

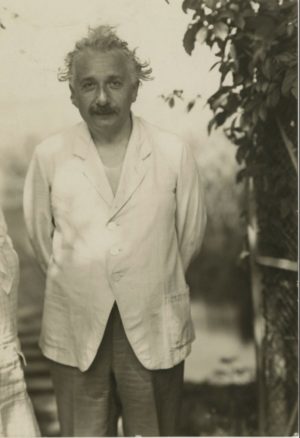

Lotte Jacobi, Albert Einstein in Caputh Germany, 1928 (Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton)

A decade earlier, Jacobi took a series of photographs of Einstein at his house in Caputh, Germany—comparably close to Berlin as Princeton is to New York City. This series featured the Einsteins sailing on the lake, and relaxing in somewhat-rumpled knit leisurewear. In these photographs from a decade earlier than the Princeton portrait, we are confronted with a leisure-time Einstein in his most comfortably casual attire. These photographs were taken seven years after he won the Nobel Prize for Physics, and would have been among the few that Jacobi was able to take with her from Germany. She was forced to leave most of her photographic prints and negatives behind, and they were destroyed by Nazis or lost.

Their friendship and collaborations continued in the U.S. Once there, Einstein helped Jacobi meet other prominent exiles in New York City, like German writer Thomas Mann, Austrian director Max Reinhardt, and his Austrian actress wife Helene Thimig, who all became Jacobi’s earliest U.S. portrait subjects.

Life Magazine and Photography

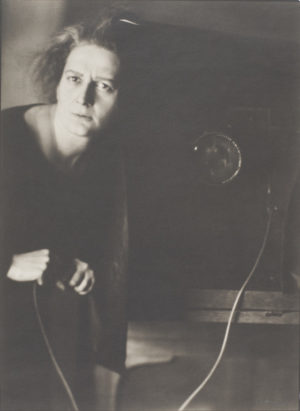

Jacobi too adopted the “messy hair, don’t care” look for her own self-portrait in Berlin. Lotte Jacobi, Self-Portrait, Berlin, platinum print, c. 1930, printed c. 1980, 36.2 × 26.35 cm (LACMA)

Jacobi’s intimate and revealing style of portraiture did not meet with the approval of Life magazine’s photo editors. Publisher Henry R. Luce required images of prominent people that reaffirmed the American public’s preconceived perceptions of them, rather than prompting new insights about their characters or inner lives. Jacobi’s portrait of Einstein in his casual bomber jacket did not convey enough gravitas for his social position.

Beginning weekly publication in 1936, Life magazine quickly became a window on the world for its largely American, white, upper middle-class, urban—and subsequently, suburban—readership. With Life, Luce, already successful with Time magazine, sought to “reveal, every week, aspects of life and work which have never before been seen by the camera’s miraculous second sight. By giving pictures their own magazine, [Life] intends that the camera shall at last take its place as the most convincing reporter of contemporary life.” [3]

Perhaps what we now find most interesting about Jacobi’s portrait is the way she captured the action of thinking performed by one of our most historically prominent thinkers. Jacobi seems to have been able to see more facets of Einstein than the editors of Life cared to share with their readership.