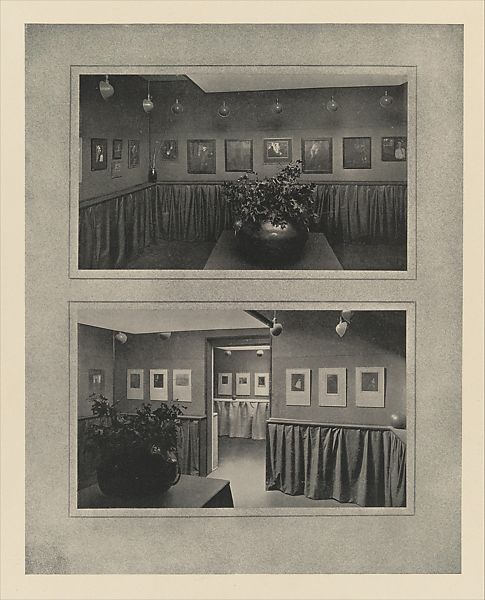

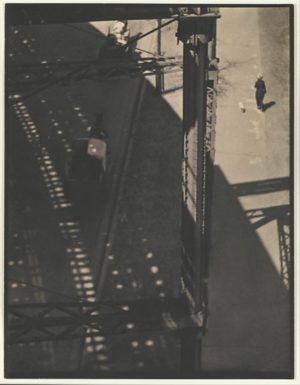

Alfred Stieglitz, “Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession,” image from Camera Work, No. 14 (April 1906) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection)

291 Fifth Avenue

If you walked into the “Little Galleries of the Photo Secession” at 291 Fifth Avenue run by New York photographer Alfred Stieglitz and his devotees between 1905–1917, you would likely have been surprised. You might have seen an exhibition of avant-garde photography or perhaps an exhibition of bizarre Cubist paintings. The latter, especially, would have been an unusual sight.

At the time, New York City was not yet well known as an artistic center. As a result, many artists and institutions in New York still looked to European cities—particularly Paris—as artistic and cultural beacons. Although Modernism was gaining ground in Europe, it held little appeal to American audiences outside of small artistic circles. Stieglitz’s 291 gallery, which exhibited modern European painting as well as the latest art photography, helped to change all of that.

Stieglitz and the art of photography

Stieglitz had become a well known photographer—perhaps the most renowned photographer in the United States—a result of his advocacy for the relatively new medium, forming camera clubs (such as the Photo Secession, in 1902), and publishing photography journals. Photography had been used to create art since its invention in the mid-nineteenth century, but it was a relative late comer in comparison to easel painting and printmaking, which had been the preferred artistic media for two-dimensional work since the end of the Renaissance.

Because photographs were created using a mechanical device (an analog camera) rather than by the artist’s hand, many artists and critics debated whether it belonged within the realm of art exhibited in galleries and museums.

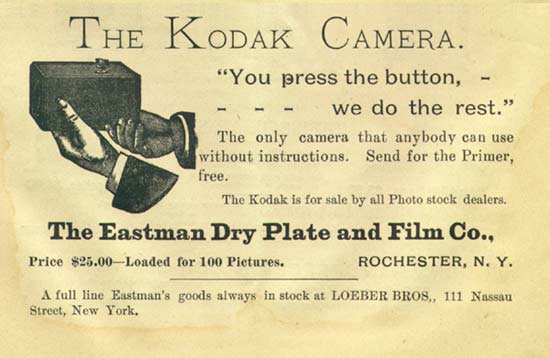

Further complicating photography’s claims to art status was the invention in 1888 by the Eastman Kodak Company of the first portable hand-held camera and the advertising slogan “you press the button, we do the rest,” making the ability to take pictures affordable and widely available to ordinary people for the first time. With photography in the hands of the masses as well as commercial studios concerned primarily with portraits, advertisements, and other practical matters, Stieglitz and fellow art photographers felt compelled to differentiate their photography from the production of commercial studios and the common snapshots of everyday life.

Alfred Stieglitz, [The Street – Design for a Poster], 1896, photogravure, 30.6 × 23.3 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

![Paul Strand, Photograph - New York [Abstraction, Porch Shadows], 1916; spring 1917, photogravure, 24.2 × 16.7 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/14197701-1-870x1214.jpg)

Paul Strand, Photograph – New York [Abstraction, Porch Shadows], negative 1916; printed spring 1917, photogravure, 24.2 × 16.7 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

Pictorialism, and later, modern life

Early in his career, Stieglitz championed a photographic style known as Pictorialism, which sought to achieve artistic, even painterly, effects that included soft focus and altering of the photograph using cropping or marking the prints with chemicals. Pictorialist photographers also preferred idealized imagery over images of modern life. Over time, however, Stieglitz shifted his approach and helped to cultivate a photographic aesthetic grounded in the idea of “straight photography.” This meant renouncing the pictorialist alteration of photographs (a practice conceived of as being too rooted in nineteenth-century practices), in favor of more sharply focused images that featured modern forms and artistically emphasized the formal elements of the image. “Straight photographers” heralded in the era of the modern photographic image. In fact, the younger photographer, Paul Strand, instigated a decidedly modernist aesthetic in photography after seeing a Cubist exhibition at 291.

The modern age, the artistic avant-garde, and “Little Gallery” known as 291

The painter and photographer Edward Steichen and other notable artists were instrumental in developing the program of exhibitions at 291, which first highlighted Photo Secessionist photographers and then went on to feature exhibitions by prominent European artists including Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, and the Cubist works of Pablo Picasso that would influence artists across media around the world. But 291 also exhibited the work of emerging American artists whose paintings and photographs explored modernity (modern life as impacted by new industrial, social, and political developments) or Modernism (the radically different artistic sensibilities avant-garde artists thought best represented modern experiences).

Georgia O’Keeffe, Yellow Calla, 1926, oil on fiberboard, 22.9 x 32.4 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

One of the American Modernists exhibiting at 291 was Georgia O’Keefe, whose abstracted urban and organic forms captivated Stieglitz and with whom he became romantically involved. The exhibitions of innovative photographs, paintings, and sculptures at 291 made it the preeminent venue for modern art in the United States in the early twentieth century.

Paul Strand, From the El, 1915, platinum print, 33.6 x 25.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) © Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive.

The Modern Metropolis

The modern skyscrapers being built in New York appealed to Stieglitz, and he was known to roam the streets of the city looking to capture its essence in his photographs. The thriving metropolis also intrigued Strand, whose photographs of the city conveyed the new modernist aesthetic. New York attracted artists from Europe as well, including Francis Picabia, a French modernist who spearheaded the New York iteration of the Dada movement (artists associated with Dada responded to the horrors of WWI by creating works that featured chance, humor, and absurdity).

Picabia had developed a rapport with Stieglitz and the artists at 291 when he visited New York for the first large-scale exhibition of modern art at the Armory Show in 1913. When he returned to New York to escape serving in WWI he spent time helping out at 291, where artists also gathered for lively discussions. Picabia experimented with a new machine aesthetic and with the idea of the photograph as a work of mechanical reproduction that would change art—including painting—forever.

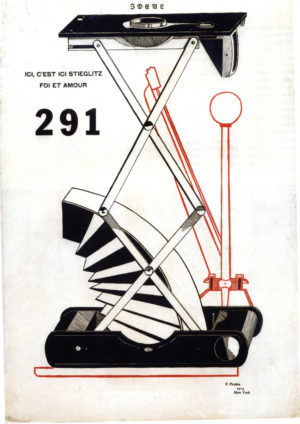

While at 291, Picabia made portraits called “Mechanomorphs” that portrayed the artists, photographers, and critics there as hybrid machines—depicting Stieglitz as an intriguing camera-like device. Such works also represented the wide array of practices supported by 291 and the idea that the gallery fostered the transmission of European Cubism and Collage (practices of cutting and rearranging images from visual culture) to artists in the United States.

Publishing, circulation, and art in visual culture

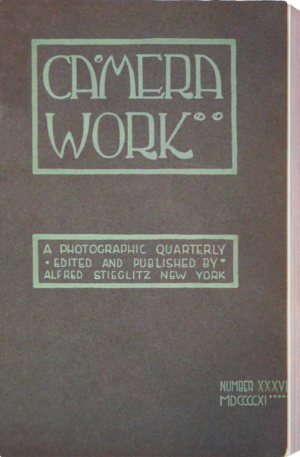

One of the activities at 291 that helped promote modern painting and photography was publishing. Stieglitz and his friend Steichen began publishing the journal Camera Work in 1903 and continued this project until 1917. During that time the journal featured illustrious art photographs and articles about photography as well as features on modern art from Europe.

The publishing efforts at 291 served as an important conduit for modern art in the United States (even for those viewers who did not pay a visit to the gallery). From 1915–1916 Stieglitz and companions at 291 published a journal of the same name. The short-lived journal 291 featured even more radically modern art—so radical in fact that few readers were interested.

Picabia’s bizarre mechanical portrait of Stieglitz (see the Smarthistory essay “Ideal”) was featured on the cover of a 1915 edition of the journal but represented another conundrum. The tendencies of some contributing artists, such as Picabia, to embrace the newly emerging Dada movement made the publication too enigmatic for general audiences and, it is said, even to Stieglitz himself.

Despite the fact that this journal seemed relevant to only a small group of artists in early twentieth-century New York, its transnational contributions and cutting-edge content remain historically significant. Like the gallery at 291, the journal’s function as a conduit for modernism in the United States has earned it a prominent place in art history.

Additional resources

Art Institute of Chicago, “Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession/291”

Eastman Museum,“From the Camera Obscura to the Revolutionary Kodak”

Beaumont Newhall, Photography: Essays and Images (Museum of Modern Art, New York 1980)

John Pultz, “Cubism and American Photography,” Aperture, no. 89 (1982), pp. 48-61