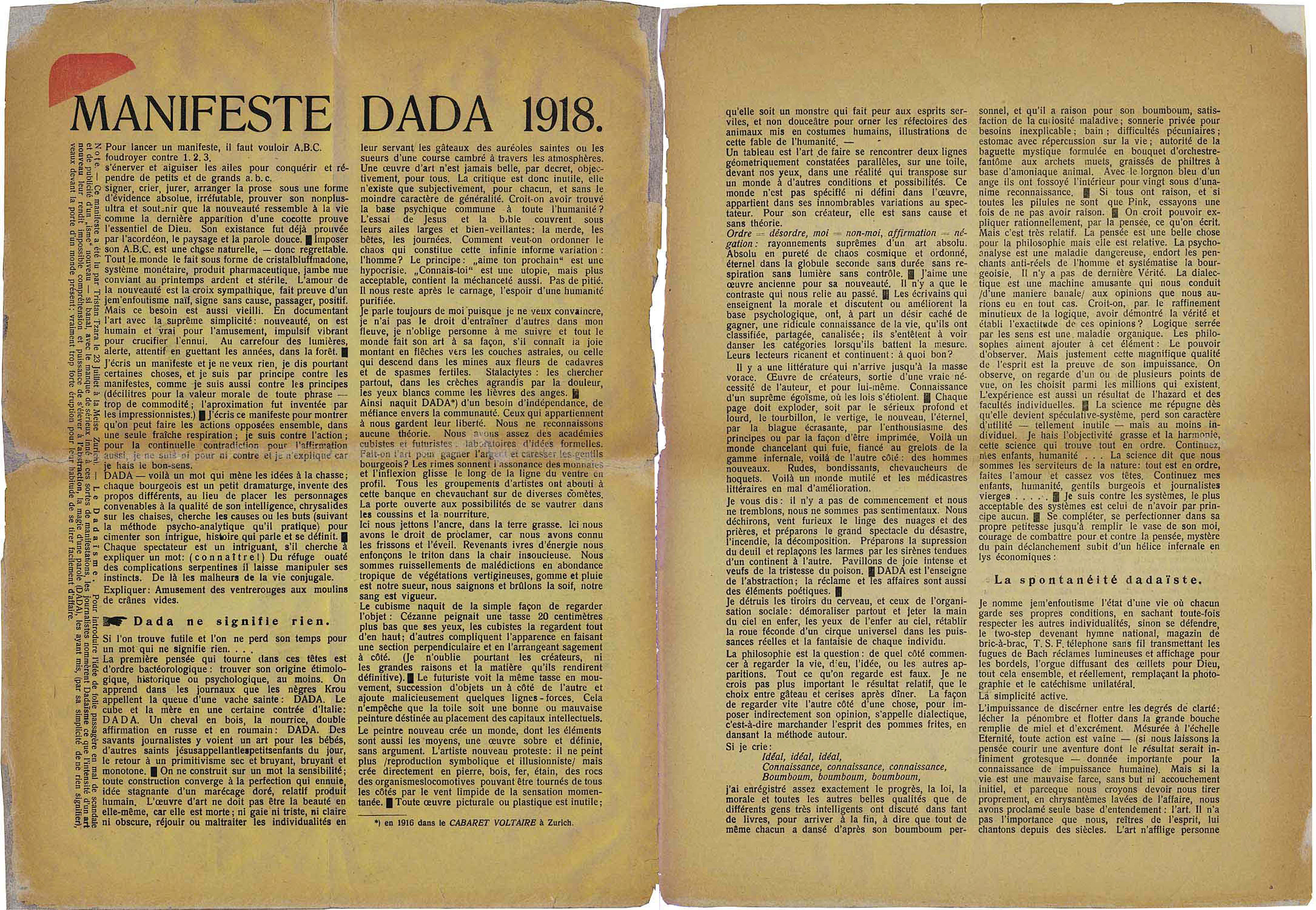

The poet Tristan Tzara was a strong advocate of the international Dada movement, but his Dada Manifesto of 1918 (which you can read in full here) appears to be complete nonsense. It is, in fact, just that — but in a really interesting way that perfectly serves the goals of the Dada movement.

An anti-manifesto manifesto

A manifesto (derived from a Latin word meaning “clear,” which is ironic in this case) is a document that states the beliefs and objectives of a group. Many manifestos are political, but artists began issuing manifestos declaring their aesthetic aims in the 1880s. Tzara paradoxically introduces his Dada manifesto with a rant against manifestos and their lists of demands:

To put out a manifesto you must want: A. B. C. / fulminate against 1. 2. 3. / fly into a rage and sharpen your wings to conquer and disseminate little abcs and big abcs / sign, shout, swear, organize prose into a form of absolute and irrefutable evidence, to prove your non plus ultra.Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918 [1]

The righteous zeal of manifestos repels Tzara, as does the way manifestos seek to impose a course of action on others. “To impose your A. B. C. is a natural thing — hence deplorable,” he insists, rather oddly, since we are used to thinking of what is “natural” as good, not deplorable.

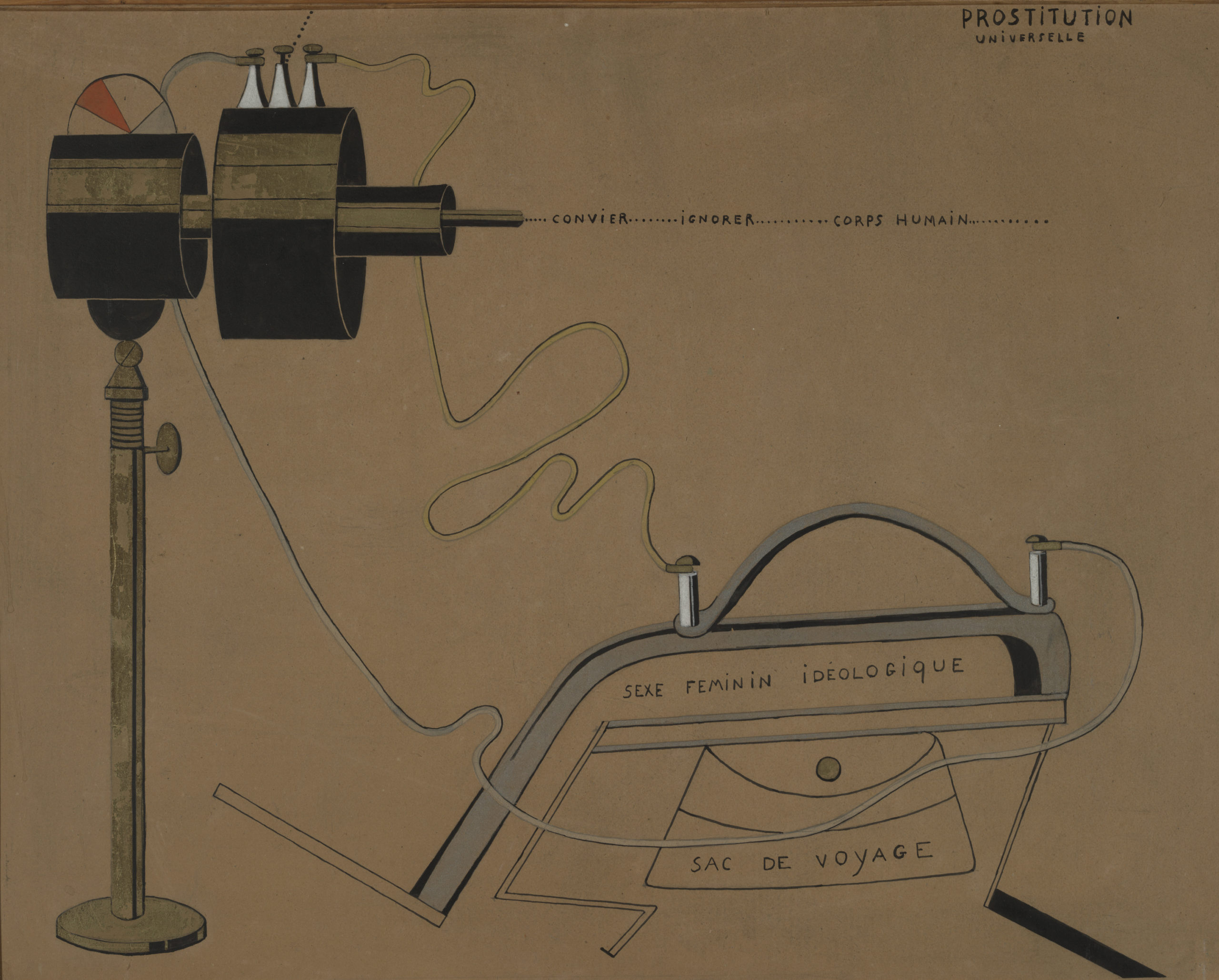

Francis Picabia, Universal Prostitution, 1916-17, black ink, tempera, and metallic paint on cardboard, 74.5 x 94.2 cm (Yale University Art Gallery)

After this opening rant Tzara slides into one of the many bewildering, free-associative broadsides that are scattered throughout the manifesto: “Everybody does it in the form of crystalbluffmadonna, monetary system, pharmaceutical product, bare leg advertising the ardent sterile spring [season].” These seemingly senseless interludes are partly a Dada strategy to prevent any extended trains of rational thought, but there is also some method to the madness. Tzara here evokes all sorts of ways that human beings find comfort, purpose, and meaning in life, such as religion, money, technology, drugs, sex, and consumerism. These false comforts are, implicitly, as deplorable as the self-righteousness that produces manifestos.

For Tzara, Dada emphatically does not want to participate in such false comforts or organized social movements, so what he is writing is an anti-manifesto manifesto:

I write a manifesto and I want nothing, yet I say certain things, and in principle I am against manifestos, as I am also against principles.Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918

Violating two basic principles of logic, Tzara here contradicts his own terms (writing a manifesto that wants nothing), and denies his own premises (he is against the very principles that makes him reject manifestos). With this sentence, Tzara introduces us to the main strategy of Dada: continuous contradiction.

Continuous contradiction

A core idea behind Dada is absurdism, a philosophical position that recognizes an inherent conflict between humankind’s constant need to search for meaning and purpose in life, and the lack of any such (knowable) meaning or purpose. “Supposing life to be a poor farce, without aim,” Tzara writes. Throughout history, people have attempted to assuage their psychological distress by asserting various meanings and purposes for life, but these are themselves contradictory (the way two different religions frequently are), and there is insufficient evidence for any of them.

Dada is based on the recognition and acceptance of the meaninglessness of life, and the last thing Dadaists want to do is to create another illusion to comfort people with a sense of purpose when there is none. The only gesture left to Dada is to tear down other people’s systems and illusions, as Tzara recognizes in scattered statements that almost read as genuine attempts at an absurdist or nihilist manifesto:

There is no ultimate truth… Does anyone think that, by a minute refinement of logic, they have demonstrated the truth and established the correctness of their opinions? … I detest greasy objectivity, and harmony, the science that finds everything in order… I am against systems, the most acceptable system is on principle to have none.Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918

Perhaps the closest that Tzara comes to making a graspable statement of the Dada creed is this:

I write this manifesto to show that people can perform contrary actions together while taking one fresh gulp of air; I am against action; for continuous contradiction, for affirmation too, I am neither for nor against and I do not explain because I hate common sense.Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918

Even in what should be a straightforward statement of the main strategy of Dada, “continuous contradiction,” Tzara recognizes that he would, in effect, be contradicting himself if he did not contradict himself and affirm affirmation as well. The fact that this is an absurd internal contradiction is not a logical flaw; it is the essence of Dada.

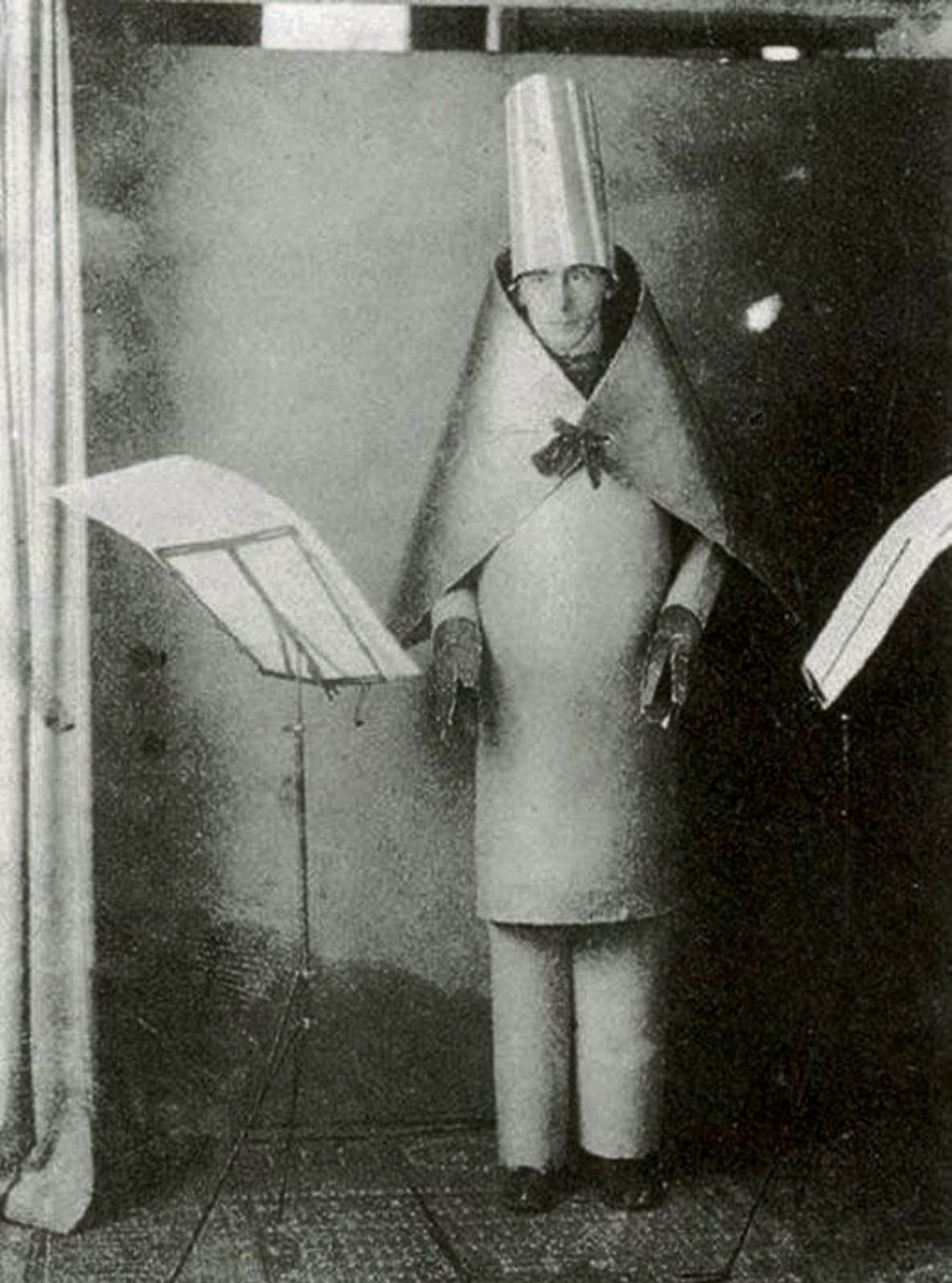

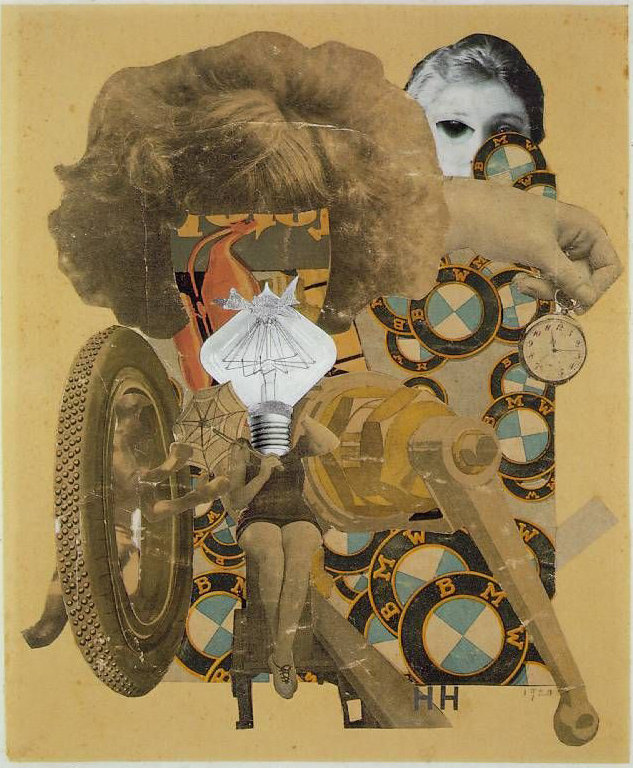

The strategy of continuous contradiction accounts in part for why so much of Dada art is offensive. That offense arises out of our consciousness of social conventions being broken or sacred cows being desecrated. Examine the works illustrated here and in the essays on Dada performance, pataphysics, collage, readymades, and politics. Notice how they violate all sorts of conventions and mock the many ways that humanity tries to make sense of and find purpose in life: religion, culture, fashion, nationalism, war, art, consumerism, technology, science, family, love, etc.

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-23, oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, and dust on two glass panels, 277.5 x 177.8 x 8.6 cm © Succession Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art) photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Radical individualism

Although Dada considers all human systems to be vain attempts to allay our terror at the meaninglessness of existence, Tzara is not a complete nihilist. Scattered throughout the manifesto are statements that suggest his belief in radical individualism. Tzara calls humankind an “infinite and shapeless variation.” There are no universal values, truths, or tastes: “Criticism is useless, it exists only subjectively, for each person separately, without the slightest character of universality. Does anyone think they have found a psychic base common to all humankind?” Any attempt to generalize knowledge or assert a universal human ideal is in vain:

If I cry out: Ideal, ideal, ideal / Knowledge, knowledge, knowledge, / Boomboom, boomboom, boomboom, I have given a pretty faithful version of progress, law, morality, and all other fine qualities that various highly intelligent people have discussed in so many books, only to conclude that after all everyone dances to their own personal boomboom, and that the writer is entitled to his boomboom.Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918

The last couple of clauses begin to suggest a value and a purpose: “everyone dances to their own personal boomboom,” and each of us is entitled to our own boomboom. Accepting such radical individualism would result in the highest state possible: freedom at least from subservience to anyone else’s system — political, religious, philosophical, ethical, economic, sartorial, sexual, or social. “Dada was born of a need for independence, of a distrust toward unity. Those who are with us preserve their freedom.”

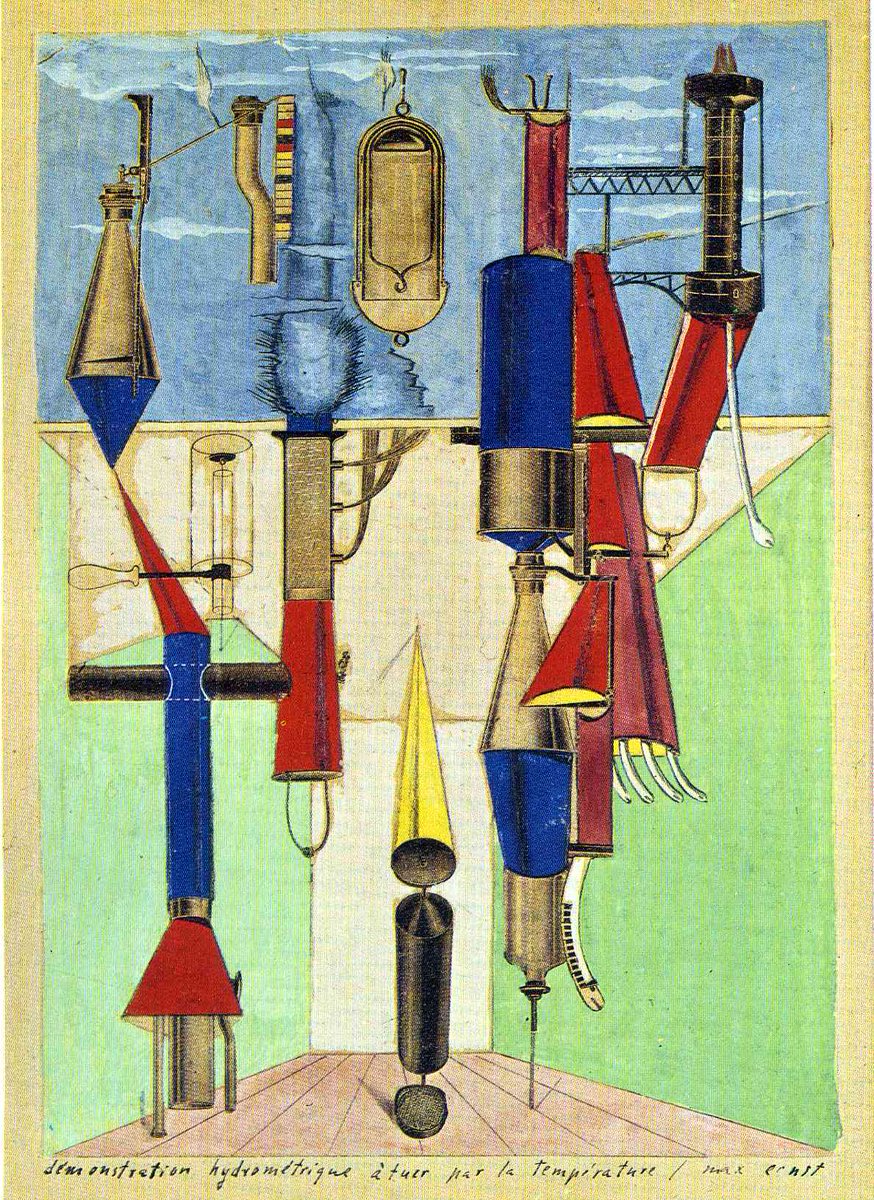

Max Ernst, Hydrometric Demonstration How to Kill by Temperature, 1920, collage, gouache, India ink, and pencil on paper, 24 x 17 cm (private collection)

What is sacrificed in this dedication to individual expression, however, is the communicative function of art. Communication requires a shared system (a language, whether verbal, visual, or otherwise), and at least an assumption of shared concepts or emotions that can be conveyed through that system. Both of these requirements imply a sacrifice of radical individualism, so Tzara freely jettisons them: “Art is a private affair, artists produce it for themselves … When a writer or artist is praised by the newspapers, it is a proof of the intelligibility of their work: wretched lining of a coat for public use.” Dada should be unintelligible: “What we need is works that are strong straight precise and forever beyond understanding.” The unintelligibility of Dada art becomes proof of its author’s freedom from any shared language, truths, or values.

In its unintelligibility, offensiveness, and contradictions, Dada reflects the fundamental absurdity of life itself. The manifesto concludes: “Dada Dada Dada, a roaring of tense colors, and interlacing of opposites and of all contradictions, grotesques, inconsistencies: LIFE.” Dada is nonsense, but very carefully produced nonsense, targeted at very specific effects: to mirror the senselessness of the universe, to shake the reader/viewer out of their seductive but false systems of belief, and to encourage us to dance to our own personal boomboom.

Notes:

- Tristan Tzara, “Manifeste Dada,” 1918, as published in Dada vol. 3 (December 1918), n.p. The English translation throughout this essay is based on the University of Pennsylvania version, but has been occasionally modified for clarity using the original French version.

Additional resources: