Stephen Mopope, 14. Buffalo Hunting Scene, 1937, mural, west wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS*)

Stephen Mopope, 2. Eagle Dancers, 1937, mural, east wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

In the narrow lobby of the Anadarko Post Office, a buffalo hunt ensues. A pair of Eagle Dancers perform their ceremonial waltz in the entryway. Over by the P.O. boxes, a Kiowa family begins the long journey south for the winter in Kiowas Moving Camp. This panorama unfolds in the small town of Anadarko, located sixty miles southwest of Oklahoma City.

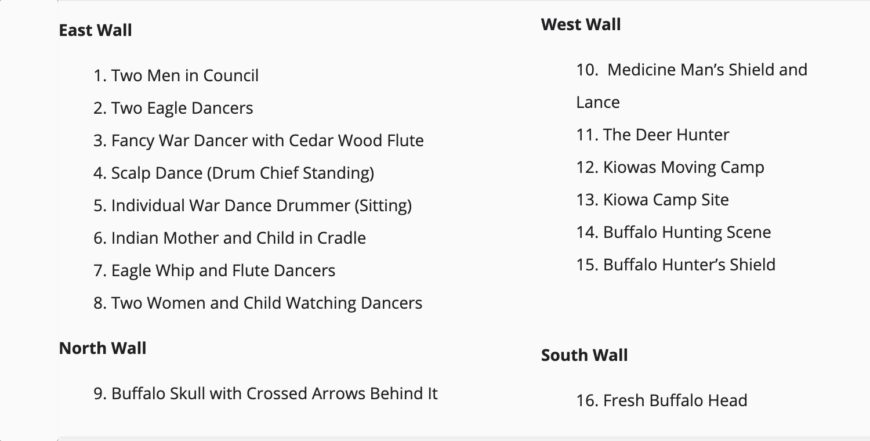

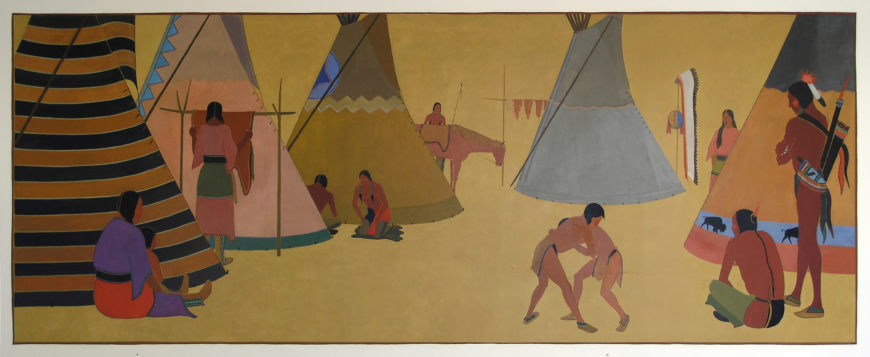

Stephen Mopope, 12. Kiowas Moving Camp, 1937, mural, west wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

With a population of just over 6,500, Anadarko is an unassuming community in the heart of the Southern Plains. The post office itself is a simple buff brick building erected in 1935, its humble appearance does not give any indication of its historical significance.

The post office in Anadarko today. It looks much the same as it did when the murals were painted.

The sixteen murals displayed within depict the life and traditions of the Kiowa people, a Plains Indian tribe. Completed by Kiowa artist Stephen Mopope in 1937, the murals comprise one of the best examples of modern Indigenous American painting in the country.

As vibrant examples of Kiowa-style painting—known for its bold, flat, and colorful aesthetic—these murals tell the story of a rich culture and the centuries-long struggle to preserve it.

The sixteen murals decorate all four walls of the narrow space, and they appear in the following order:

The Murals

The Anadarko murals depict scenes of Kiowa life, past and present. Some panels, like 14. Buffalo Hunting Scene (top of the page) and 13. Kiowa Camp Site, illustrate life before the arrival of white colonists to the Plains. Other panels, including those depicting ceremonial dancers, highlight Kiowa traditions still practiced today. In this way, artist Stephen Mopope achieved a portrait of Kiowa history and culture traversing time and place.

Stephen Mopope, 13. Kiowa Camp Site, 1937, mural, west wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

Thematically arranged according to the seasons, the murals also create a cyclical narrative. The story of a buffalo hunt—central to the Kiowa way of life—is told in sequence from the northern to southern walls.

Stephen Mopope, 1. Two Men in Council, 1937, mural, northeast corner of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

Two Men in Council and the Sun Dance

In the northeast corner of the lobby, the story begins with 1. Two Men in Council. Sitting against a flat ochre background, two men prepare for the annual Sun Dance. The man on the left draws our attention to the man on the right by pointing towards his ceremonial fan of feathers. This fan identifies the wielder as the chief of the Sun Dance. Once the most important of all Kiowa rituals, the Sun Dance was held every summer between June and July to encourage the return of the bison herds. As the Kiowa depended on the bison for sustenance, the Sun Dance was a crucial ceremony. However, we do not see a depiction of this sacred dance in Mopope’s murals. The absence of a Sun Dance panel is significant because the Bureau of Indian affairs outlawed the Sun Dance in the 1890s in an attempt to suppress Indigenous spiritual practices.

Stephen Mopope, 7. Eagle Whip and Flute Dancers, 1937, mural, east wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

Eagle, Scalp, and War dancers

Stephen Mopope, 4. Scalp Dance (Drum Chief Standing), 1937, mural, east wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK

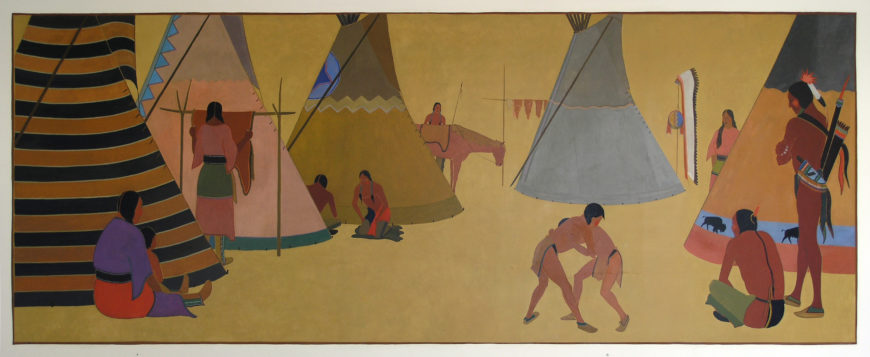

As we move along the eastern wall, representations of Eagle, Scalp, and War dancers emphasize the diverse range of Kiowa ritual practices. The Kiowa adopted the Eagle Dance (shown in 2. Eagle Dancers at the top of the essay) from the Taos Pueblo tribe with whom they traded. Performed biannually, the Eagle Dance is a way of lifting up the prayers of the tribe. The leaders of the dance are distinguishable by the eagle wing bone whistles they carry in their mouths.

Stephen Mopope, 5. Individual War Dance Drummer (Sitting), 1937, mural, east wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

The Scalp Dance, on the other hand, was a ritual of thanks and celebration, typically performed after a successful war raid. Triumphant warriors would present enemy scalps as trophies and tell of their heroics while a band of drummers, led by the Drum Chief, played an accompanying score.

Stephen Mopope was himself an accomplished interpreter of Kiowa war dances, performing often at Indian fairs and powwows throughout the southwest. For the artist, painting was another form through which to preserve Kiowa traditions like these.

Stephen Mopope, 14. Buffalo Hunting Scene, 1937, mural, west wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

Buffalo Hunting Scene

When we arrive at the large 14. Buffalo Hunting Scene along the south wall, it becomes apparent that the annual Sun Dance was a success. Three men, armed with bois d’arc (“bow wood”) spear and bows and arrows, pursue the bison on horseback. Treacherous prairie dog holes threaten to trip them up at any moment. The frantic eyes of the bison and the horses speak to the chaotic nature of the hunt, yet, the gaze of each Kiowa hunter remains calm and focused, affixed firmly to their targets.

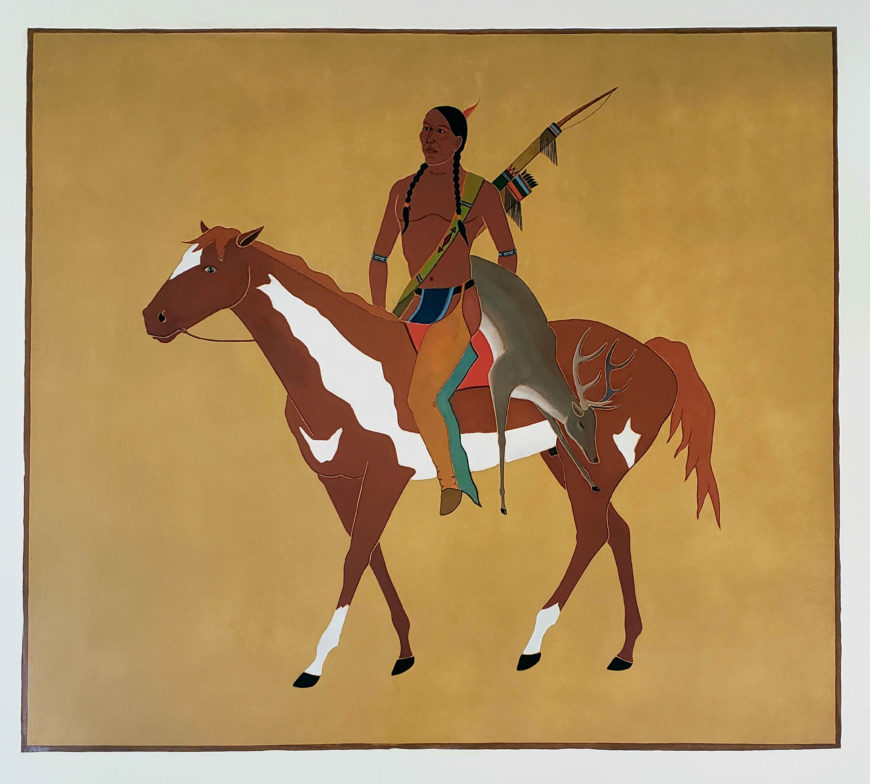

In eliminating extraneous background detail, Mopope’s minimalistic style of painting emphasizes only the most important elements of a scene. In 14. Buffalo Hunting Scene we note the poise of the hunters, the manic movement of the animals, the trickle of blood emanating from an arrow wound in the hide of a bison, a lone prairie dog fleeing the turmoil and jumping headfirst into its burrow. This narrowing of focus heightens the tension, highlights the action, and allows the viewer to see clearly all of the details being presented. The silhouette of every feather in the hunter’s headdress, the cut of his buckskin leggings, the decorative pattern on a quiver—all of this jumps out against the bare backdrop. This graphic style of painting is not only eye-catching, but highly legible, effectively conveying information about the appearance and customs of the Kiowa people.

Stephen Mopope, 12. Kiowas Moving Camp, 1937, mural, west wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

Migration of the Kiowa

A great deal of information is conveyed in panels like 12. Kiowas Moving Camp, which showcases the annual migration of the Kiowa as they follow the bison herds south. In this panel, a mother and daughter drag a buffalo skin tipi behind their horse. It was the job of Kiowa women to sew and construct the tipis. Following behind them is a young boy towing the tipi poles. Flanking the group, two male guards keep watch.

Stephen Mopope, 13. Kiowa Camp Site, 1937, mural, west wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

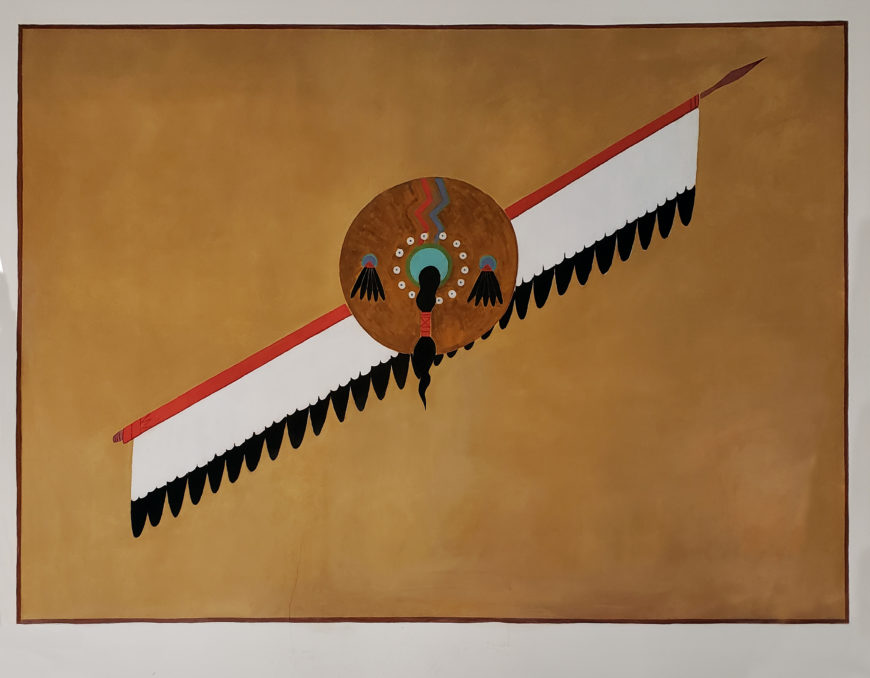

Stephen Mopope, 15. Buffalo Hunter’s Shield, 1937, mural, west wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

In 13. Kiowa Camp Site, the members of the group have erected their winter home. On the left-hand side of the composition, a woman is seen tanning a bison hide. Children wrestle in the foreground while men and women watch in repose, a stark contrast to the high-octane energy of the hunting scene. In the background of the camp site, a buffalo hunter’s shield hangs alongside a feathered war bonnet.

On the western wall of the lobby, Mopope paints a panel dedicated to this very shield, named as 15. Buffalo Hunter’s Shield. Decorated with the image of two bison facing a rainbow, the ceremonial shield serves as a symbol of a fruitful hunt and a healthy winter season.

Stephen Mopope, 9. Buffalo Skull with Crossed Arrows Behind It, 1937, mural, north wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

Stephen Mopope, 16. Fresh Buffalo Head, 1937, mural, south wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

The seasonal cycle

The seasonal cycle of the mural series is summarized by two bison heads set on opposing walls. 9. Buffalo Skull with Crossed Arrows Behind It represents the desolation of winter. The bison skull appears picked clean by vultures and bleached white by the sun. In contrast, 16. Fresh Buffalo Head suggests the new bounty of the summer hunt. Together they form a chain of summer and winter, life and death, sacrifice and jubilation.

Stephen Mopope, 3. Fancy War Dancer with Cedar Wood Flute, 1937, mural, east wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

History

The Anadarko murals were a result of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives. The New Deal (1933–1939) comprised a series of public works projects designed to provide employment opportunities for American workers and to lift the country out of the depths of the Great Depression. One such initiative in 1934, when the U.S. Treasury Department’s Section of Fine Arts began commissioning artists to decorate federal buildings nationwide. Between 1934 and 1943, the Section of Fine Arts commissioned 1,600 works of art for post offices across America. These works were intended to capture the spirit and history of American life. Many of the resulting pieces depicted Native American subjects, yet most of the artists behind these works were not themselves Native. This discrepancy raises necessary questions about representation and autonomy as many of these federal murals depict Indigenous subjects through a white lens. More often than not, these works cast Indigenous subjects as stereotypes, curiosities, and as caricatures of the fearsome “savage.” The European-American philosophy of Manifest Destiny not only forced Indigenous tribes from their ancestral land, but it reimagined their ancestral identities as well, stealing from them both physically and culturally.

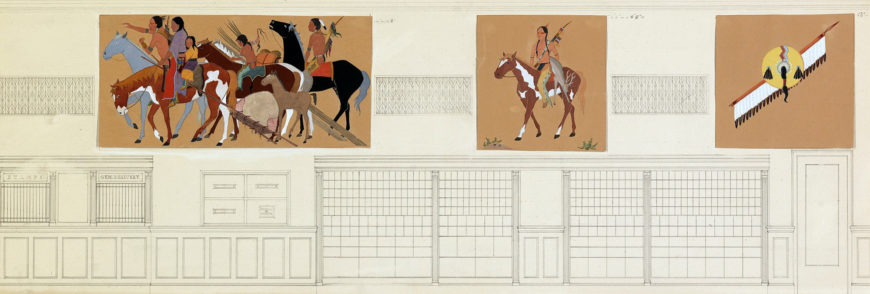

Stephen Mopope, Kiowas Moving Camp, mural study of the west wall showing panels 10–12 (from right to left), 1936, Anadarko, Oklahoma federal building, 1936, gouache and pencil on paper mounted on paperboard (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Stephen Mopope’s contribution to the project stands out as an important example of an Indigenous artist representing his own culture. The result is a more authentic, accurate, and intimate expression of Native life. His selection for the project is also a testament to the history of the Anadarko Post Office and its former identity as the Kiowa Indian Agency of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (the title of which is still on the building’s façade).

Stephen Mopope working on 11. Deer Hunter mural on the west wall of the Anadarko Post Office, Oklahoma, 1939 photograph, 5″x7″ (National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum)

In February of 1937, The Oklahoma News announced that Anadarko’s new post office would be granted a federal mural. “Oklahoma will have something as typical of the state as its comic-opera politics, its crude oil and dust storms,” the newspaper declared. [1] Indeed, Stephen Mopope’s paintings would be more than typical, capturing an aspect of the region predating all but the dust storms. In large part, the content of Mopope’s murals depicted Oklahoma as it was before the arrival of white colonists.

Stephen Mopope, 6. Indian Mother and Child in Cradle, 1937, mural, east wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

At this point in time, Oklahoma had been a state for only thirty years. Anadarko itself had formed in the late 19th century out of a consolidation of Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache reservations. These reservations were themselves established through a series of one-sided treaties, like the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867, in which the U.S. government relocated Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands. Raised in an environment of government oversight and forced assimilation, Stephen Mopope sought to faithfully record different facets of Kiowa culture in his work.

Stephen Mopope, 8. Two Women and Child Watching Dancers, 1937, mural, east wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

The Artist

Stephen Mopope is widely considered the most prolific of his generation of Kiowa painters and the preeminent member of the group known as the Kiowa Six. Active during the early-to-mid twentieth century, the Kiowa Six gained widespread recognition following their participation in Prague’s First International Art Exhibition of 1928. A portfolio of their work entitled Kiowa Indian Art was subsequently published in France. The group consisted of Stephen Mopope, Spencer Asah, James Auchiah, Jack Hokeah, Lois Smoky, and Monroe Tasatoke. Asah and Auchiah would assist Mopope in executing his designs for the Anadarko murals on a large scale.

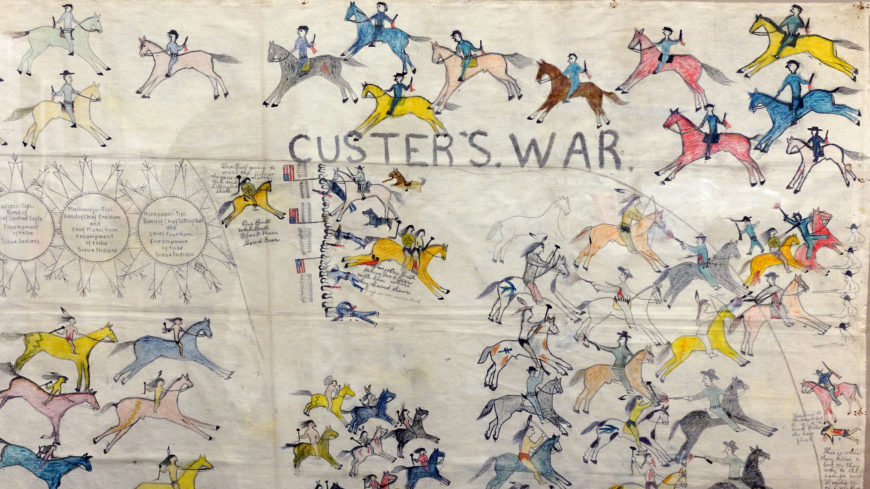

An example of ledger drawing. One Bull/Tȟatȟáŋka Waŋžíla (Hunkpapa Lakota), Custer’s War (detail), c. 1900, 39 x 69 inches (irregular), pigments, ink on muslin (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

This generation of Kiowa artists typically worked with watercolor or gouache on paper. From an early age, Stephen Mopope exhibited an affinity for the arts, which was encouraged by his granduncle, the ledger artist Charles Oheltoint (also known as Charlie Buffalo). Ledger drawing was a unique form of Plains Indian art so named for the type of ruled paper used in its creation. Featuring scenes of hunts, battles, and dances set against blank backgrounds, ledger art closely resembles the tipi decoration and hide painting practiced by Plains Indians for generations. To these traditional art forms, ledger drawing incorporated materials like crayons and ruled paper introduced through contact with European-Americans. From hide painting, to ledger art, to the watercolor painting of the modern Kiowa, the changing circumstances of the Plains Indians is discernible through the materials used in their artistic practice.

Having trained in traditional Kiowa painting under his granduncle, Mopope continued his artistic studies under the guidance of Susan Ryan Peters, Field Matron of the Anadarko Kiowa Agency. Peters served as a mentor to the Kiowa Six. She encouraged their work and sponsored courses in European art methodology to be taught in Anadarko. At St. Patrick’s Mission School, a local Catholic school for Native children, Mopope received further instruction in perspective and proportion.

In the 1920s, Peters encouraged Mopope and the rest of the Kiowa Six to enroll in the University of Oklahoma’s art program. It would be the school’s director, Oscar Jacobson, who then introduced the Kiowa Six to a wider audience when he arranged their first touring exhibition. As head of the Oklahoma division of the Federal Art Project, Jacobson also facilitated Mopope’s Anadarko Post Office commission, which was the largest ever assigned to a Plains Indian artist.

Stephen Mopope, 10. Medicine Man’s Shield and Lance, 1937, mural, west wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK

In part because of these connections with white America, Mopope’s work has sometimes been interpreted as a hybrid style—part Kiowa, part European-American. Contemporary critics alternately compared his bold compositions to the iconographic images of the ancient Egyptians and to the streamlined simplicity of European modernists. In the former comparison, Mopope was labeled a type of primitive, painting relics from antiquity. In the latter, he was assimilated into a tradition and a culture that was not fully his.

Stephen Mopope, 11. The Deer Hunter, 1937, mural, west wall of the Anadarko Post Office, OK (photo: USPS)

Mopope’s Anadarko murals not only showcase his unique style of painting, but they place the artist firmly in his own historical narrative. Though Summer turns to Winter, though the Kiowa who populate the post office lobby were forced from the open plains to the consolidated reservation, Mopope’s murals keep their tradition and their history alive. Restored in 1974 and having undergone their most recent conservation in 2018, Stephen Mopope’s murals are visible to the public year-round at the Anadarko Post Office.

Notes:

[1] Ruth Robinson, “Tribal Traditions to be Recorded on Walls of Anadarko’s Post Office by Trio of Kiowa Indians,” The Oklahoma News, Sunday February 21, 1937, p 6.

Additional resources:

Read more about the murals on The Living New Deal

Read about Mopope’s mural in the Udall Department of the Interior in Washington D.C.

Watch another video about Millard Sheets’ Tenement Flats on Smarthistory that addresses the New Deal

Bell, Betty and Riffel, Carolyn. “Anadarko (town).” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Anadarko (town) | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture (okhistory.org)

Ellison, Rosemary. Contemporary Southern Plains Indian Painting (Oklahoma Indian Arts and Crafts Cooperative: Anadarko, OK. 1972).

Greiner, Alyson L and White, Mark A. Thematic Survey of New Deal Era Public Art in Oklahoma; 2003-2004 (Department of Geography: Oklahoma State University. 2004).

Kracht, Benjamin R. “Kiowa (tribe).” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Kiowa (tribe) | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture (okhistory.org).

Noah, Reuben. “Two Eagle Dancers” in Indians at the Post Office: Native Themes in New Deal-Era Murals. Virtual exhibition: Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Two Eagle Dancers | National Postal Museum (si.edu).

Ruth Robinson, “Tribal Traditions to be Recorded on Walls of Anadarko’s Post Office by Trio of Kiowa Indians,” The Oklahoma News (Sunday February 21, 1937), p 6.

“Indian Themes.” USPS Inventory of New Deal Art in Post Offices: Oklahoma Division. December 28, 1989.

“U.S. Post Office.” City of Anadarko: Anadarko, OK. Welcome to City Of Anadarko.