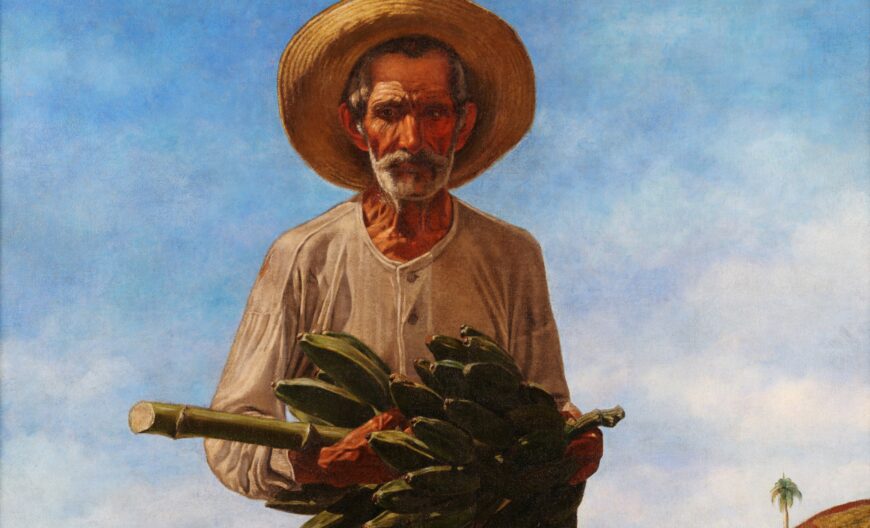

Ramón Frade, Our Daily Bread, 1905, oil on canvas (Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, San Juan)

Ramón Frade created an icon with his 1905 painting Our Daily Bread. The figure of an older man dominates the composition. He is frontal and monumental. Set in the center foreground, we look up at him as he rises high above the mountainous landscape in the background. The weathered lines of his face are rendered in great detail, as are the prominent veins of his hands and feet that speak of age and a life of labor in the mountains and valleys of Puerto Rico.

The painting and its origin

The scene is set in the countryside of Puerto Rico, in a geography reminiscent of the area of Cayey, where the artist lived most of his adult life. The jíbaro walks barefoot on a dirt path, dressed in tan pants and a thin, white shirt with a small rip below the right shoulder. He cradles in his arms a bunch of mafafo bananas (a type of plantain), fruits that have long been a staple of the Puerto Rican diet. The machete he used to cut down the bundle hangs from his waist from a rope and a straw hat covers his graying hair. The man’s gaze is directed toward the viewer; he is tired but dignified as the sun lights half of his face.

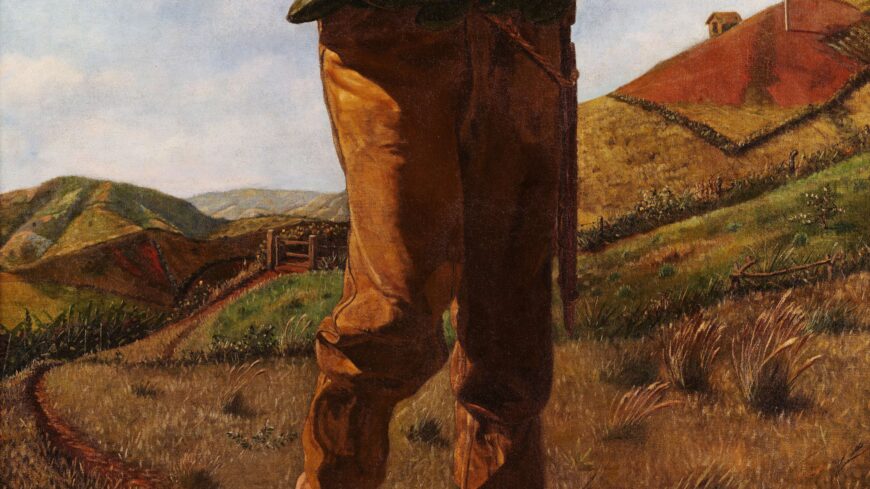

Path (detail), Ramón Frade, Our Daily Bread, 1905, oil on canvas (Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, San Juan)

Our eyes move left to follow the path that leads to the banana field (on the lower left corner, we see tall banana leaves) where the man harvested the fruit he carries. As the path continues to the right, it becomes fenced off behind a small wooden gate. The fence wires create a diagonal line that allows us to cross the landscape to the right side of the composition.

Bohío (detail), Ramón Frade, Our Daily Bread, 1905, oil on canvas (Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, San Juan)

The fencing is mirrored by the rising slope of a hill, crowned by a small, wooden bohío and a lone palm tree. The gentle incline of the mountains in the middle ground are painted in the varied shades of green and ocher of the dry season in spring. Mountains fade into the cloudy horizon, which is crowned by a bright blue sky.

Frade produced this painting as a show of skill when requesting financial aid from the government to study art in Italy. He sent it to the Chamber of Delegates in San Juan, where the almost five-foot-tall painting was exhibited and well-received by local politicians and journalists. Painter Francisco Oller was consulted on the artistic merit of the painting and with his endorsement the stipend was approved. [1] Unfortunately, the decision was reverted by Regis H. Post, the U.S. assigned Secretary of State. After numerous tries, his request was finally approved in 1907 by Governor Beekman Winthrop; Frade would spend four months in Italy. [2]

While Frade was already a professional artist, he had been interested in visiting Europe to augment his formal artistic training. He was born in Cayey, Puerto Rico, but was soon adopted by a well-off Spanish-Dominican family after the death of his biological father. He lived for most of his childhood in Spain before spending his youth in the Dominican Republic where the family settled in 1885. In the capital of Santo Domingo, he started his training first at the Municipal Drawing School with Felipe de los Santos, before studying painting with French artist Adolphe Laglande.

Frade would go on to work as an illustrator for different publications in the Dominican Republic before setting up a painting studio in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. He traveled extensively around the Caribbean and Latin America. While still living in Hispaniola he periodically visited his biological family in Puerto Rico and saw the economic and political precariousness accelerated by the changes brought by the Spanish-American War, before moving back to his hometown around 1902.

The jíbaro as national symbol in the wake of U.S. occupation

Everything seen here—from the old farmer with his machete and pava to the mountains with the wooden bohío—speaks of Puerto Rican national identity. The jíbaro became a national and cultural symbol of Puerto Rico in 19th-century literature and painting. Publications like Manuel Alonso’s El Gíbaro and artworks like Oller’s The Wake sought to represent local traditions and people in order to identify what was distinctly Puerto Rican. This process of recognition and representation occurred in Spanish Puerto Rico, as many considered the region and themselves in light of independence struggles in continental America as new republics like Colombia and Chile sprang up and severed ties with their once dominant European colonial administrations. Artists, writers, and intellectuals found in the rural population the character and ways of being that they believed set Puerto Ricans apart from the Spanish.

However, Frade painted this image in a different context. In 1898, the United States military invaded Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American War. By the end of the year, the archipelago became a possession of the United States after the signing of the Treaty of Paris. This treaty marked the end of the conflict between Spain and the U.S., and along with Puerto Rico it brought other Spanish territories (like Guam and the Philippines) under U.S. control.

Puerto Rico was ruled by the U.S. military until 1900, when a civilian government was established with the Foraker Act. This legal act had immense repercussions on Puerto Rico’s future. The U.S. appointed governors and high-ranking officials, controlled importation/exportation guidelines, and severely limited the influence that Puerto Ricans had on their own political and economic situation. People living in the territory did not have the same rights as those in the U.S., political limitations that carry over into the present.

The U.S. occupation provoked a wide array of reactions that evolved as the new administration put their policies into play. A segment of the population welcomed the new relation with the U.S., moved by dissatisfaction with Spain, while others considered the possibility of a union with the U.S. that maintained Puerto Rico’s political autonomy. Others worked toward independence, rejecting the United States as another colonial regime.

Jíbaro (detail), Ramón Frade, Our Daily Bread, 1905, oil on canvas (Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, San Juan)

The first decades of U.S. administration were marked by uncertainty and economic hardship for most of the population. The U.S. administration promoted the agrarian economy, particularly the sugar industry. U.S. and foreign-owned corporations bought up land for sugarcane and, along with poor labor conditions, created an exploitative industry that benefited few Puerto Ricans. Most of the labor was carried out in valleys and flat terrain close to the coastline and well suited for sugar cane. This, combined with the decline of the coffee industry in the mountains, exacerbated the economic strain of the rural, interior population. The new administration also brought Americanization policies, including the imposition of English in schools, a policy that was deeply resented. The Americanization policies provoked significant local resistance and fueled national anti-U.S. sentiment.

Artists like Frade found in the representations of jíbaros a way to push back against the cultural and political situation. This extended to an interest in the local landscape and traditions, present both in the visual arts and literature as a trend referred to as jíbarismo. [3] Our Daily Bread carried an undeniable political weight.

An identity considered imperiled by foreign influence

Here the jíbaro is representative of the population of the mountainside, impoverished and forced to move either to urban centers or abroad. Bigger than the landscape itself, the figure is not limited to the region; he encapsulates an identity considered imperiled by foreign influence. The Spanish-speaking jíbaros with their music and traditions were the perfect subjects with which to visualize the colonial struggle.

Ramón Frade, La Planchadora, 1948, oil on masonite (Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, San Juan)

Frade continued to respond to this in his work with compositions that idealized rural life in the mountains based on his observations and photographs of the people of his town. Our Daily Bread is clearly inspired by costumbrismo and could almost be considered a genre painting, yet the monumentality conferred to the jíbaro transforms it into something else. Even the title, a phrase found in The Lord’s Prayer, links the image to a sense of religiosity. The jíbaro’s daily labor producing and harvesting for a rural population becomes a religious act.

Frade would return to this same composition on eight different occasions, translating it into watercolor and smaller oil paintings as late as 1950. [4] Something about the painting interested Frade throughout his career, perhaps the desire to capture an identity he considered threatened by the new political reality.