Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, and dust on two glass panels, 277.5 × 177.8 × 8.6 cm © Estate of Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, looking at a large piece of broken glass.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:10] A work of art by Marcel Duchamp. This is “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,” also known as “The Large Glass.” Dates to 1915, but he worked on it until 1923, made many studies, wrote a book about it, and declared it in 1923 definitively unfinished.

Dr. Zucker: [0:31] When he would eventually unpack it after it had been shipped, relating to an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, and he found that both large panes had been shattered, he declared it complete.

Dr. Harris: [0:42] He reassembled all the pieces of glass, and decades later he installed it here at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Dr. Zucker: [0:49] This is not a painting, they’re not even painted pieces of glass. Instead, he’s using lead wire, lead foil, and dust, which he said he cultivated in his apartment in New York City, that he used as the pictorial material.

Dr. Harris: [1:03] The choice of glass is a funny one because in Western painting, there’s an idea of painting as a window through which we look into a world that’s as real as the world that we’re standing in, but this is so definitively abstracted, so unreal.

Dr. Zucker: [1:21] It’s interesting, because this work of art is not the kind of abstraction that we think of often when we think of work that’s being produced in 1915 by people like Kazimir Malevich or even Picasso. This is not in that tradition of formal abstraction of geometries, this is an abstraction of ideas.

Dr. Harris: [1:39] When we look closely, we do start to see forms that are recognizable.

Dr. Zucker: [1:43] Duchamp actually created what he called “The Green Box.” This was a small container that included notes and clippings that described the meanings and the elements within “The Large Glass.” What’s interesting is that “The Green Box” contain[s] loose pieces of paper that can be read in any order, so that the meaning is always in flux. Nevertheless, he does name specific elements.

Dr. Harris: [2:04] We shouldn’t look for certainties of meaning anywhere here.

Dr. Zucker: [2:09] Absolutely. Art historians have sometimes fallen into a trap of trying to be definitive. Nevertheless, if we start at the bottom, on the left side, we see a series of forms, which Duchamp called “malic moulds.” Malic was a word that just simply for Duchamp meant male, a word that he made up. He often created linguistic forms.

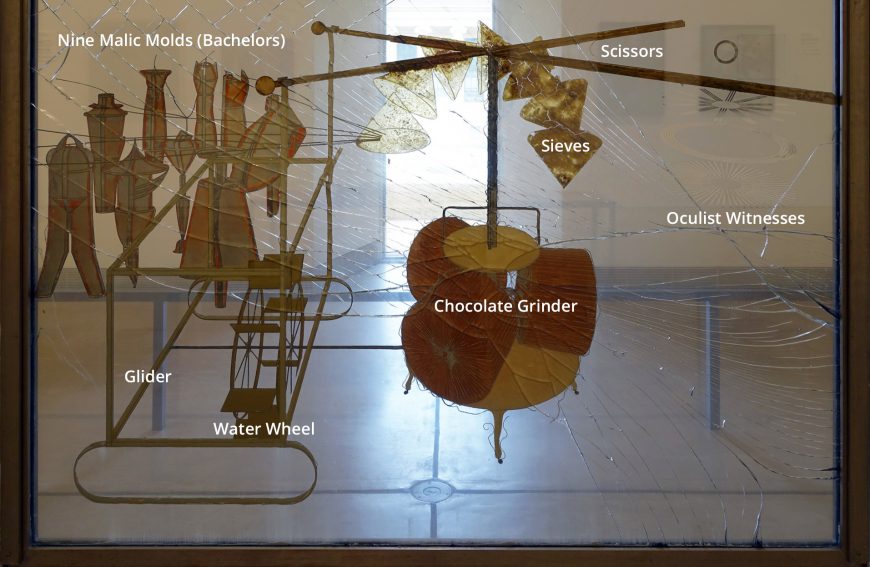

[2:28] In the center, at the bottom we see what he referred to as a chocolate grinder. Above that, a series of sieves and giant scissors, and to the right, a little bit difficult to see, and seen obliquely, are optical devices.

Dr. Harris: [2:43] What are we to make of the female realm and the male realm, the bachelors at the bottom, and the bride at the top? Clearly, the realm of male and female, but also, a sense of sexual desire, the bride is stripped bare by her bachelors. We have a sense of male suitors, of male desire, and of the availability of a female form that stimulates that desire.

Dr. Zucker: [3:11] Or lack of availability. One of the ways that “The Large Glass” is read is that it’s desire that powers the machinery but activates everything that’s being rendered here, both in the realm of the female and the realm of the male, but none of it consummated.

Dr. Harris: [3:24] It feels to me like he’s making fun of the way that, especially in the 19th and 20th century, human beings try to make things rational, try to explain things, even things as absurd as human desire.

Dr. Zucker: [3:38] And the way in which the rational could be dangerous. Think about when this was made. This was made in 1915. This was during the First World War, one of the most violent conflicts in human history.

[3:48] What was so startling about that war is that it took place with modern machinery: the machine gun, early tanks, mustard gas. There was a level of violence that was thanks to our industrial, rational world, and here we see the reintroduction of the irrational.

Dr. Harris: [4:05] You could argue, too — and of course, this is an important part of the Dadaist movement in the early 20th century — that art, in many ways: the sale of art, the marketability of art, the schools of art, all of these institutions were part of a system that led to the violence of the war, and so how could art be outside of that?

Dr. Zucker: [4:27] Well, Duchamp is rejecting oil on canvas. He’s rejecting bronze sculpture, marble sculpture, and he’s trying to find a way to deconstruct the meanings that have always driven the desire of the art market.

[4:39] Not only were the materials not traditional, but the method of making wasn’t traditional either. There was chance that was introduced. There was absurdity in the construction of the object itself.

[4:50] A good example of that can be seen in the holes that are drilled in the upper right corner. The idea behind this reminds us that there is interaction between the two realms. The males shoot upward trying to hit those squares that we see in the thought bubble, in the imagination of the female.

Dr. Harris: [5:08] We do have this sense at the bottom of churning, this endless machine processing, this frustrated desire that’s not fulfilled.

Dr. Zucker: [5:19] And violence, the male realm shoots towards the female. The holes that we’re seeing that are drilled are actually the result of Duchamp firing a toy cannon at the upper area, missing the female form, but then the artist would drill wherever the toy cannon actually hit the glass.

Dr. Harris: [5:36] We have this immediate difficulty because we want to have an idea of art that is something that’s intentionally made by the artist, that’s beautifully crafted, and firing a toy cannon and then drilling where that toy cannon hits completely turns that idea upside down.

Dr. Zucker: [5:52] And can be seen as a direct attack on the notion of intentionality and a reintroduction of the idea of the irrational.

Dr. Harris: [5:59] So how do we not read that as also a making fun of us, who are here looking at this art so very seriously that he fired a toy cannon at?

Dr. Zucker: [6:08] There’s no question that much of Duchamp’s work, including “The Large Glass,” functions as a kind of entrapment for art historians, for the traditions through which we understand art in the Western tradition.

[6:18] Duchamp’s approach to creating art would have a profound impact, especially on the second half of the 20th century. People like Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, or so many of the artists of the postwar era that have rethought the foundational ideas that have driven art for so long.

[6:34] When we were looking at this work, I was looking originally for a signature. For Duchamp, the signature was so important in transforming what he called a “readymade” into a work of art. That is, of transforming a ready-made object in the world, something that he had not created, into something that we looked at differently.

[6:51] This work is itself inherently a signature. The top is the realm of the bride. The first three letters of the word in French for bride is “mar,” M-A-R. The bottom, the first three letters of the word for bachelor would be “cel,” C-E-L. Together they spell, of course, his first name. The entire work is, in a sense, a kind of wordplay and a kind of signature.

[7:15] [music]

You might know Marcel Duchamp because of his Fountain—the urinal that he signed (as R. Mutt) and submitted to the Society of Independent Artists art show in 1917. This “readymade” was a whimsical and iconoclastic gesture—in keeping with the spirit of the New York Dada circle. Like his Dada compatriots, including Francis Picabia and Man Ray, Duchamp reveled in humor, wordplay, and the radical redefinition of art during and just after World War I.

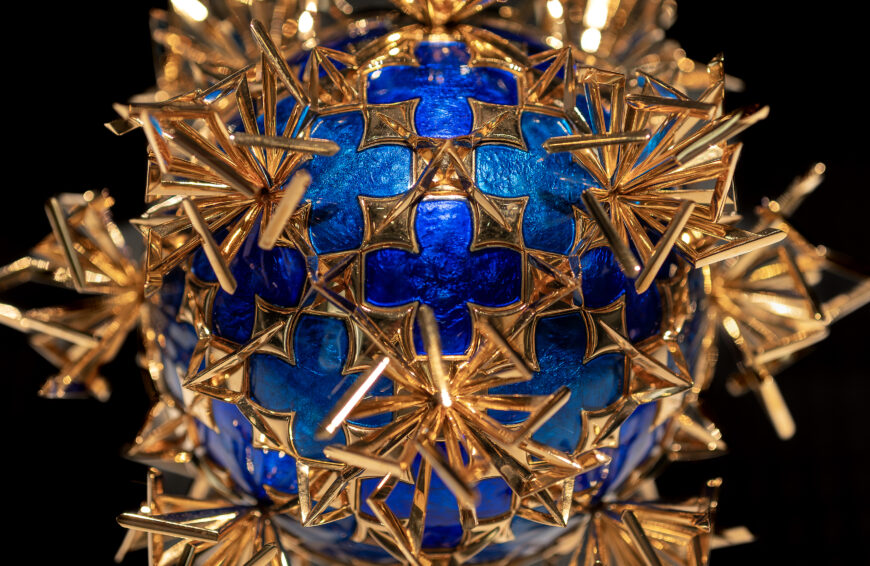

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-23, oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, dust, two glass panels, 277.5 × 177.8 × 8.6 cm © Succession Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Art driven by ideas

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917/1964, glazed ceramic with black paint (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

Even before Fountain, Duchamp had made a big splash at New York’s 1913 Armory Show with his controversial cubo-futurist painting Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) (1912).But Duchamp said he wanted to get away from painting as a strategy for art-making. This was partly a reaction against the popular French saying, “bête comme un peintre,” which means “stupid as a painter” (a phrase used to describe someone foolish—much like the English “dumb as a box of rocks”). To say someone is “stupid as a painter” is to say that painters only translate what they see and that painting is not an intellectual activity. Duchamp disagreed, and strove to make works, like Fountain, that were driven by intellect (what would come to be known as “conceptual art”) and defied standards of beauty and artistic technique. Duchamp called The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even his “hilarious picture” and it, too, engages wit, absurdity, non-traditional materials, and conceptualism to push the boundaries of what was acceptable and possible in the art world of his generation.

Dust, wire, glue and varnish

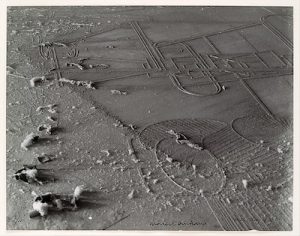

Man Ray, Dust Breeding, 1920, printed c. 1967, gelatin silver print, 23.9 x 30.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even is often called the Large Glass because that is precisely what it is: two pieces of glass, which are stacked vertically and framed like a double-hung window to reach over nine feet tall. Though the Large Glass is essentially a flat, two-dimensional object, it is emphatically not a painting, as it is mostly transparent—you can walk around it and view it from both sides—and Duchamp avoided using traditional materials like canvas and oil paint. Instead, he concocted the imagery on the glass surface out of wire, foil, glue, and varnish. He also allowed dust to collect on the glass as it laid flat in his studio, which he affixed with adhesive. Man Ray’s photograph, Dust Breeding (1920), shows just how dirty the glass got.

Duchamp stopped working on the Large Glass in 1923, after eight years, not because it was complete, but because he decided it should remain “definitively unfinished.” Later, in 1927, when the glass was en route to collector Katherine Dreier’s house from an exhibition in Brooklyn, he was thrilled to discover it had been damaged, saying the accidental cracking finished the work in a way that he never could have.

Marcel Duchamp, Malic Molds and shattered glass (detail), The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-23, oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, dust, two glass panels, 277.5 × 177.8 × 8.6 cm © Succession Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

The Large Glass is a curious contraption; it looks a bit like a mechanical diagram and was designed it to function like an allegorical machine. He made preliminary paintings and drawings for components of the Large Glass including Chocolate Grinder (No. 2) (1914). He also amassed an impressive collection of cryptic notes that he brought together in The Green Box (1934), which scholars have used to interpret the work’s many different meanings—from the frustrations of love and sex, to the physics of electromagnetism and the fourth dimension. To understand how the Large Glass works like a machine we must imagine its components in motion.

Marcel Duchamp, Annotated detail, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-23, oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, dust, two glass panels, 277.5 × 177.8 × 8.6 cm © Succession Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

The bride and the bachelors

The action begins in the upper left corner with the “Bride,” the element that resembles a bug or a tree. She flirts by stripping for the “Bachelors” in the lower register. The Bachelors are the nine vaguely anthropomorphic cylinders in the lower left section of the glass, and they think the Bride is very attractive. Each Bachelor is trying to win her affection, but they exist in a completely different zone, and are having a hard time communicating with her.

Marcel Duchamp, Annotated detail, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-23, oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, dust, two glass panels, 277.5 × 177.8 × 8.6 cm © Succession Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

As the Bachelors become excited their forms fill up with what Duchamp called an “illuminating gas” (invisible). This gas causes an “imaginary waterfall” to turn the water wheel (mill) beneath them. That action makes the rectangular glider slide back and forth, which moves the scissors above, which makes the chocolate grinder churn. All of that motion builds up, as the gas from the Bachelors flows into the cone-shaped sieves. The gas that represents the Bachelors’ desire for the Bride transforms into liquid and flows into the lower right corner. Next, the liquid is propelled through the three circular elements, and through a magnifying glass (Oculist Witnesses), and shoots into the Bride’s realm above. The goal for each Bachelor is to land his shot within one of the three square windows inside of the cloud that hovers at the top of the glass (Draft Piston or Nets). If he can do that, he will win the Bride and they will be able to consummate their love physically. If you look closely, you can see nine small holes on the right side of the Bride’s register, which Duchamp marked by firing matches with paint on the tips through a toy cannon. Unfortunately, only one of those shots even came close to its target. Thus, the Bachelors cannot reach the Bride and their love for her remains unfulfilled.

Marcel Duchamp, Nine Shots (detail), The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-23, oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, dust, two glass panels, 277.5 × 177.8 × 8.6 cm © Succession Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Marcel Duchamp, Oculist Witnesses (detail), The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-23, oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, dust, two glass panels, 277.5 × 177.8 × 8.6 cm © Succession Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Duchamp loved science. To create the Large Glass, he experimented not only with new media but also with recent scientific theories as if he were in a laboratory. On top of the tale of amorous attraction and frustration, Duchamp layered ideas about such scientific phenomena as electromagnetism and telegraphy. The way the Bride communicates her erotic feelings from her pane of glass to the Bachelors’ realm below relates to the power of electricity and the vibratory waves in the electromagnetic field mobilized in wireless telegraphy. The Bride’s form actually resembles the telegraphic antenna on the top of the Eiffel Tower that was the source of much popular interest in Duchamp’s day. As an antenna, she can send and receive unseen messages through space, but the Bachelors are not so advanced. They are able to receive her communications, but their only response comes in the form of those failed shots from the toy canon, which are at best a rudimentary and rather pathetic means of winning her love.

Duchamp’s writings reveal that he imagined the Bride’s realm as the mysterious fourth dimension of space, a higher plane from the Bachelors who live in our common three-dimensional world. This accounts for their miscommunications and failed attempts at finding love. In the Large Glass, Duchamp brought art, science, sex, and love together in an absurdly humorous way. Watching machines try to fall in love; imagining the bug-tree-antenna Bride strip for Bachelors who cannot reach her; understanding that the object was made with dust, shattered glass, and marks made randomly by a toy cannon; and tying that drama to the complicated workings and invisible forces of science is surprising, playful, and oddly hilarious.

Marcel Duchamp, Chocolate Grinder (detail), The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-23, oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, dust, two glass panels, 277.5 × 177.8 × 8.6 cm © Succession Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

From art to chess

After this project ended, Duchamp claimed to give up his career as an artist and became a professional chess player. His final joke was the revelation upon his death in 1968 that he had been working secretly on a major installation, Étant donnés (1946-66), for twenty years. This surprised even those who knew him well, and built upon many of the themes of eroticism and physics that he explored in the Large Glass. You can see both, along with Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), Fountain, and many other works by Duchamp, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.