Abdoulaye Ndoye, Ahmed Baba, 2013, ink and henna on paper, 16 1/8 x 11 x 1 ¾ (dimensions when folded closed), lives and works in Dakar, Senegal (The Newark Museum of Art, © Abdoulaye Ndoye)

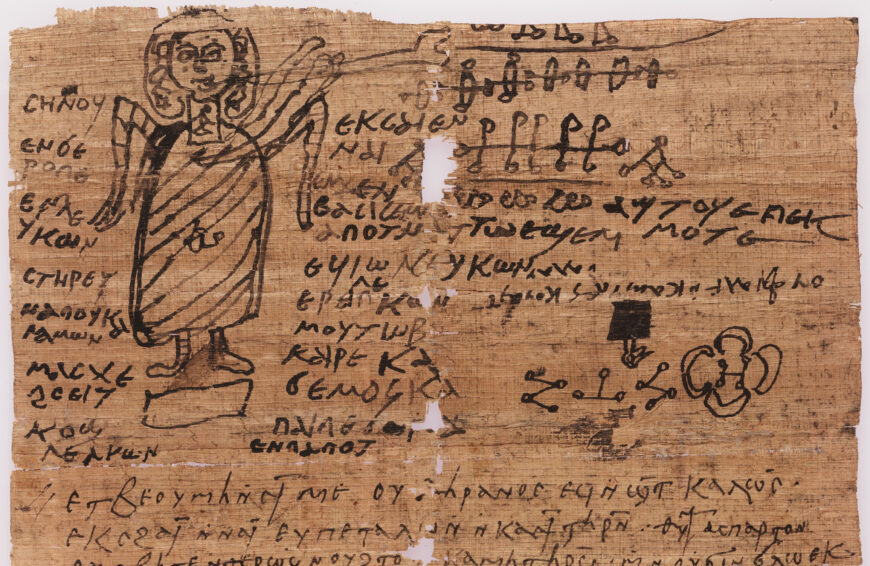

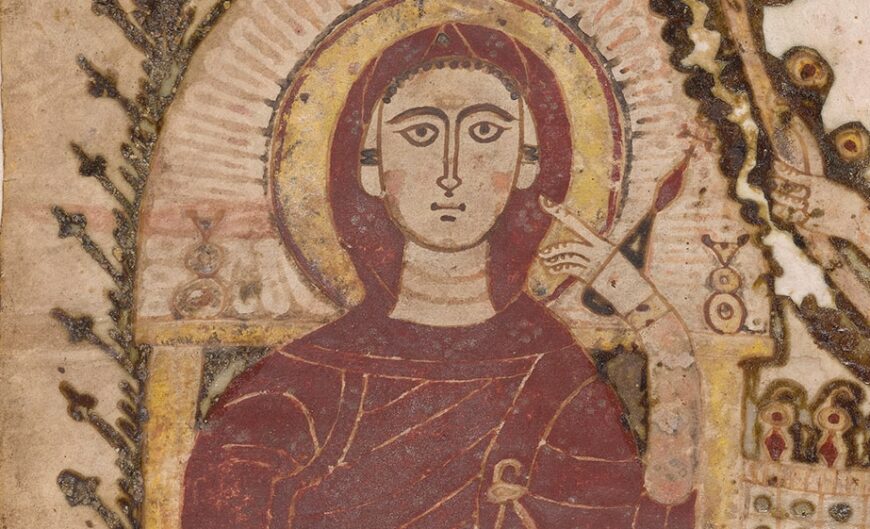

The book unfolds like an accordion, stretching across the length of a table. At first glance, it appears to be an ancient map or perhaps a long-lost manuscript, its pages yellowed like parchment. Thick, dark lines undulate and radiate across the surface, tracing the irregular contours of an uncertain topography. In the spaces between, what appears to be finely detailed script flows across in horizontal waves, row upon row, but ultimately proves illegible.

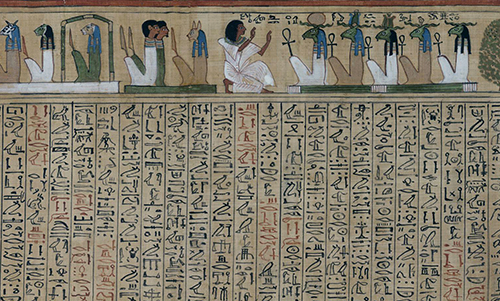

Abdoulaye Ndoye, Ahmed Baba (detail), 2013, ink and henna on paper, 16 1/8 x 11 x 1 ¾ (dimensions when folded closed), lives and works in Dakar, Senegal (The Newark Museum of Art, © Abdoulaye Ndoye)

Dakar-based artist Abdoulaye Ndoye describes this work, part of a larger series of artist’s books, as poesie graphique, or visual poetry. He combines writing, drawing, and painting to create layered compositions, saturated with washes of henna pigment and meticulously filled with invented script inked onto the surface. The resulting works are not meant to be “read” but instead invite the viewer on a visual journey, exploring the beauty of the inscriptions and designs and the subtle interplay of form and texture. They are informed by the artist’s own travels, representing an accumulation of ideas, materials, and techniques.

Celebrating Ahmed Baba

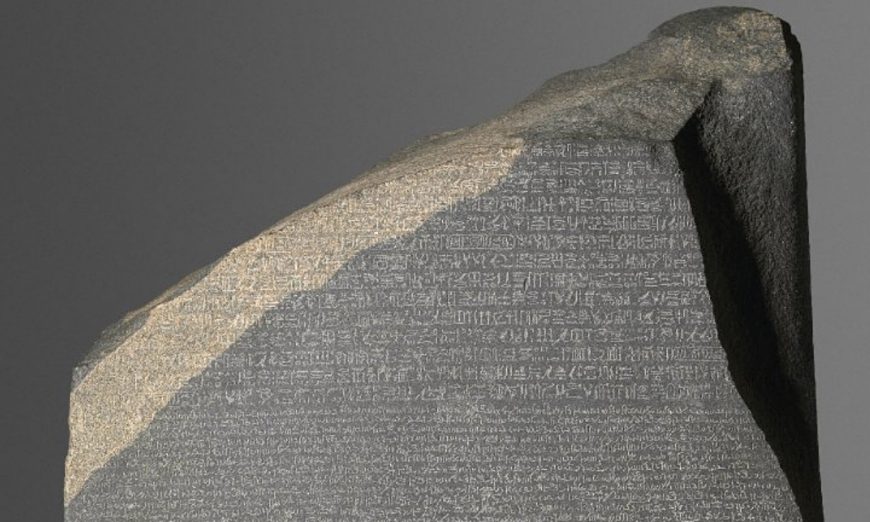

Ahmed Baba is based in part on Ndoye’s research on manuscripts and cultural heritage, an area of interest first begun in 2009. It was created as an outgrowth of Ndoye’s participation in a 2013 workshop about archives and manuscript preservation hosted by the Ahmed Baba Institute of Higher Learning and Islamic Research in Timbuktu (Mali), founded in 1973. The name of the Institute—as well as the title of Ndoye’s work—honors Ahmed Baba al-Massufi al-Timbukti, a celebrated medieval Islamic scholar and writer.

Ahmed Baba was born in 1556 near Timbuktu, which was an important center of regional trade, cultural exchange and Islamic learning during the Songhai empire. Hailing from a long line of jurists, he is credited with writing over 50 books, including theological and legal treatises, an influential biographical dictionary, and a grammar of Arabic still used in northern Nigeria. He also amassed an extensive library of thousands of books. In 1594, after the conquest of Timbuktu by the Sultan of Morocco, Baba was accused of political resistance and exiled to Marrakesh until 1608.

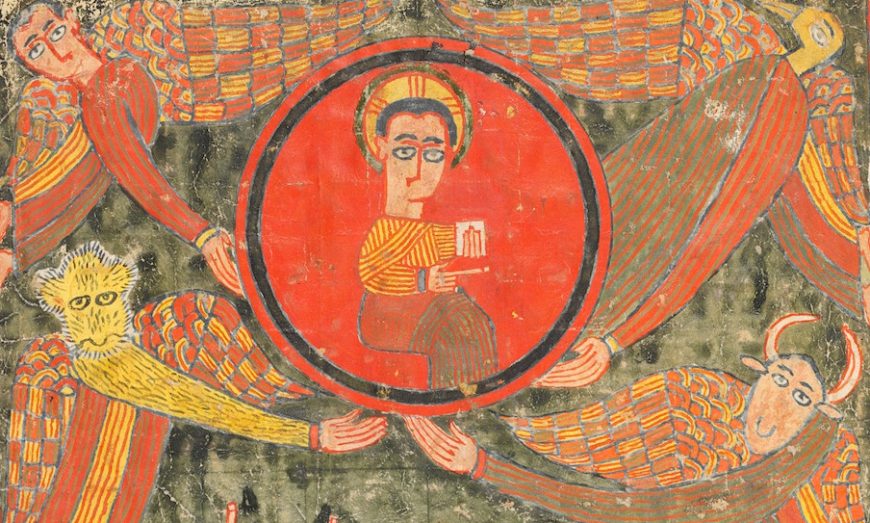

The Ahmed Baba Institute, the only public library in Timbuktu, is a research center and repository for a historically significants collection of over 20,000 manuscripts. They primarily date from the 14th to 16th centuries and cover much of Malian history. The books are mostly written in Arabic, though some are also in local languages such as Songhai, Tamashek, and Bamanankan on subjects including astronomy, medicine, poetry, literature, and Islamic law. In 2012, in the wake of the Malian coup and subsequent political instability,Timbuktu was occupied by Islamist rebels who targeted cultural and religious sites perceived as idolatrous according to their strict interpretation of religious beliefs. Many of the Institute’s manuscripts, and thousands more from private libraries in Timbuktu, were pre-emptively moved to secure locations. They were thus preserved when the rebels set fire to the library of the Ahmed Baba Institute and destroyed or severely damaged many of the city’s historic buildings in January 2013 (under the supervision of UNESCO, these manuscripts are now being digitized).

Materials and motifs

Ahmed Baba relates both formally and conceptually to Ndoye’s experiences in Timbuktu and his participation in the 2013 workshop organized in the aftermath of—and in response to—this destruction of cultural heritage. Ndoye became interested in the artistic implications of manuscripts, exploring writing not just as a mode of communication but in relation to the recording and safekeeping of cultural heritage.

The work was made using a blank book given to him by a fellow artist from China. The pages have been treated on either side with washes of henna pigment, which Ndoye employs both for its cultural significance as well as for artistic effect. The natural dye has a long history of use in West and North Africa, where it is associated with good fortune and painted on women’s hands and feet for celebratory occasions such as weddings. On the pages of the book, Ndoye has applied the pigment with a broad brush in successive layers not only as a reference to tradition but also to achieve a color and texture much like an age-worn document. This is overlaid with a palimpsest of invented script and organic patterns in ink.

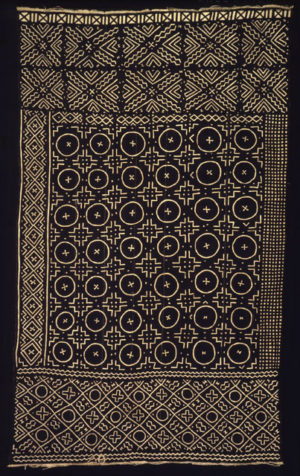

Guancho Diarra, woman’s wrapper (bògòlanfini), 1985, cotton, vegetal dye, 61 5/8 x 35 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art)

The patterns and motifs of the book are inspired by regional artistic traditions, including the hand-dyed fabric known as thioup and painted bògòlanfini (mudcloth) aswell as henna designs. Art historian Joanna Grabski, who has written extensively about Ndoye’s artistic practices, describes how these aesthetic appropriations inform the conceptual concerns underlying this work. She observes that “not only are many of these forms and motifs typically associated with ethnic identities, they are also subsumed as national and global heritage in post-independence era cultural politics…. His work underlines that both manuscripts and formal motifs associated with heritage in the Sahel are subject to interpretation as well as reinvention. They are adaptable and translatable to new mediums and expressive forms.” [1]

The artist’s book

The format that Ndoye adopts here—the artist’s book—was introduced an artistic genre at the turn of the 20th century in the Western world. During the first half of the century, artists’ books were associated with avant-garde movements, adopted to more widely disseminate art and ideas, subvert traditional market systems and to experiment with form. In the 1950s and 60s, artists such as Dieter Roth and Ed Ruscha began to experiment with the form conceptually. The genre gained popularity with artists in the U.S. and Europe from the 1970s onward. In Africa, however, artists have only recently begun to engage the genre.