Figure: Seated Portuguese Male, 18th century (Edo peoples, Court of Benin, Nigeria), brass, 12.7 x 5.1 x 6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Enslavement in the Americas

Western trade with Africa was not limited to material goods such as copper, cloth, and beads. By the 16th century, the transatlantic slave trade had already begun, forcibly bringing Africans to the newly colonized Americas. While some forms of enslavement had existed in Africa, the sheer number of enslaved people traded across the Atlantic was unprecedented, as over 11 million Africans were brought to the Americas and the Caribbean over a period of four centuries. Driven by commercial interests, the slave trade peaked in the 18th century with the expansion of American plantation production, and continued until the mid-19th century. By the late 18th century, the slave trade began to wane as the abolitionist movement grew. Those who survived the forced migration and the notorious Middle Passage brought their beliefs and cultural practices to the Americas.

Within this far-flung diaspora, certain cultures—such as the Yoruba and Igbo of today’s Nigeria and the Kongo from present-day Democratic Republic of Congo—were especially targeted. Enslaved Africans brought few, if any, personal items with them, although recent archaeological investigations have yielded early African artifacts, like the beads and shells found at the African burial grounds in New York’s lower Manhattan, which date to the 17th and 18th centuries.

The influence of Africans in the Americas can be seen in diverse forms of cultural expression, such as open-front porches and sloped hip-roofs. The religious practices of Haitian Vodou have roots in the spiritual beliefs of Dahomean, Yoruba, and Kongo peoples. Some elements of cuisine in the American South, such as gumbo and jambalaya, derive from African food traditions. Certain musical forms, such as jazz and the blues, reflect the convergence of African musical practices and European-based traditions.

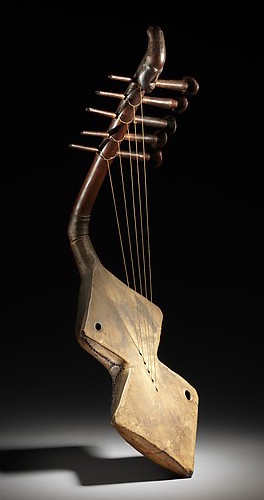

Figurative Harp (Domu), 19th–20th century (Mangbetu peoples, Democratic Republic of the Congo), wood, hide, twine, brass ring, 67.3 x 21.6 x 30.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

European colonization of Africa

Although the slave trade was banned entirely by the late 19th century, European involvement in Africa did not end. Instead, the desire for greater control over Africa’s resources resulted in the colonization of the majority of the continent by seven European countries. The Berlin Conference of 1884–85, attended by representatives of fourteen different European powers, resulted in the regulation of European colonization and trade in Africa. Over the next twenty years, the continent was occupied by France, Belgium, Germany, Britain, Spain, Italy, and Portugal. By 1914, the entire continent, with the exception of Ethiopia and Liberia, was colonized by European nations.

The colonial period in Africa brought radical changes, disrupting local political institutions, patterns of trade, and religious and social beliefs. The colonial era also impacted cultural practices in Africa, as artists responded to new forms of patronage and the introduction of new technologies as well as to their changing social and political situations. In some cases, European patronage of local artists resulted in stylistic change (for example this Mangbetu Figurative Harp) or new forms of expression. At the same time, many artistic traditions were characterized as “primitive” by Westerners and discouraged or even banned.

Although African artifacts were brought to Europe as early as the 16th century, it was during the colonial period that such works entered Western collections in significant quantities, forming the basis of many museum collections today. African artifacts were collected as personal souvenirs or ethnographic specimens by military officers, colonial administrators, missionaries, scientists, merchants, and others to the continent.

Plaque: Equestrian Oba and Attendants, c. 1550–1680 (Edo peoples, Court of Benin, Nigeria), brass, 49.5 x 41.9 x 11.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

In an act of war initiated by Britain against one of its colonies, thousands of royal art objects were stolen from the kingdom of Benin following its defeat by a British military expedition in 1897. European nations with colonies in Africa established ethnographic museums with extensive collections, such as the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, the Völkerkunde museums in Germany, the British Museum in London, and the Musée de l’Homme in Paris (now housed at the Musée du Quai Branly). In the United States, which had no colonial ties to Africa, the nascent study of ethnography motivated the formation of collections at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Field Museum in Chicago. In 1923, the Brooklyn Museum became the first American museum to present African works as art.

African independence

Independence movements in Africa began with the liberation of Ghana in 1957 and ended with the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa during the 1990s. The postcolonial period has been challenging, as many countries struggle to regain stability in the aftermath of colonialism. Yet while the media often focuses on political instability, civil unrest, and economic and health crises, these represent only part of the story of Africa today.

Martin Rakotoarimanana, Mantle (Lamba Mpanjakas), 1998 (Merina peoples, Imerina village, Antananarivo or Arivonimamo, Madagascar), silk, 274.3 x 178.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Contemporary art in Africa

In spite of Africa’s political, economic, and environmental challenges, the postcolonial period has been a time of tremendous vigor in the realm of artistic production. Many tradition-based artistic practices continue to thrive or have been revitalized. In Guinea, the revival of D’mba performances in the 1990s, after decades of censorship by the Marxist government, is one example of cultural reinvention. Similarly, in recent years, Merina weavers in the highlands of Madagascar have begun to create brilliantly hued silk cloth known as akotofahana, a textile tradition abandoned a century ago.

Photography, introduced on the continent in the late 19th century, has become a popular medium, particularly in urban areas. Artists like Seydou Keïta, who operated a portrait studio in Bamako, Mali, in the colonial period, set the stage for later generations of photographers who captured the faces of newly independent African countries. It is also important to mention developments in modern and contemporary African art. During the colonial period, art schools were established that provided training, often based on Western models, to local artists. Many schools were initiated by Europeans, such as the Congolese Académie des Arts, established by Pierre Romain-Desfossé in 1944 in Elisabethville, whose program was based on those of art schools in Europe. Less frequently, the teaching of modern art was initiated by Indigenous Africans, such as Chief Aina Onabolu, who is credited with introducing modern art in Nigeria beginning in the 1920s. Since the mid-20th century, increasing numbers of African artists have engaged local traditions in new ways or embraced a national identity through their visual expression.

Magdalene Anyango N. Odundo, Untitled, 1997, red clay, 50.2 x 33 x 26.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) © Magdalene A.N. Odundo

Artists in today’s Africa are the products of diverse forms of artistic training, work in a variety of mediums, and engage local as well as global audiences with their work. In recent decades, contemporary artists from Africa, both self-taught and academically trained, have received international recognition. Kenyan-born Magdalene Odundo, for example, was trained as an artist in schools in Kenya and in England, where she now lives. The burnished ceramic vessels she creates, which are purely artistic, embody her diverse sources, including traditional Nigerian and Kenyan vessels as well as Puebloan pottery traditions of New Mexico. The work of contemporary African artists like Odundo reveals the complex realities of artistic practice in today’s increasingly global society.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)