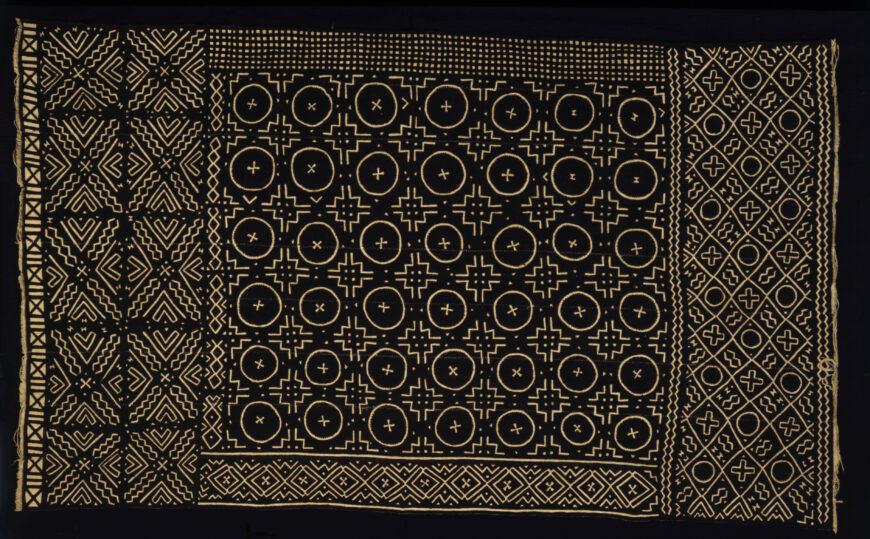

Guancho Diarra, woman’s wrapper, 1985, cotton, vegetal dye, Mali, 61 5/8 x 35 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art)

This wrapper, designed to worn around woman’s waist, exemplifies the skill of Malian artist Guancho Diarra, a master in the art of bògòlanfini. This textile tradition is distinguished by its unusual technique of using fermented mud as dye. Its name, in fact, translates as “cloth made with mud” in the Bamana language. Today, bògòlanfini is among the most recognizable of Africa’s textile traditions, appreciated and imitated around the world for its distinct geometric patterns in contrasting dark and light tones. Its roots, however, are in the Beledougou region of central Mali, where the centuries-old art form has been traditionally made by Bamana women.

Guancho Diarra made this cloth in 1985 in Kolokani, a small village in the heart of Beledougou renowned for its production of exceptional examples of bògòlanfini. Her work is notable for its clarity of design, complex patterning and symmetrical layout.

Creating bògòlanfini

The process of Creating bògòlanfini is complicated, requiring specialized knowledge and practiced skill. As typical of most artists in this region, Diarra likely used the techniques and patterns she learned from her mother and grandmother.

This wrapper began with a flat, rectangular cloth made from long strips of fabric sewn together. The strips were woven by men using locally grown cotton thread and sold in large rolls at area markets. Diarra then prepared the cloth by soaking it in water infused with leaves from the n’tjankara and n’gallama trees, a tannin-rich mixture that helps the fabric absorb the mud dye. The cloth takes on a yellowish tint after drying in the sun.

Bògòlanfini artists like Diarra must have extensive knowledge of plants and other organic materials to create the mud dye. Some have their own recipes, which may be passed down between women in a family intergenerationally and are closely guarded secrets. In general, an artist collects iron-rich mud from a stream bed and adds crushed leaves to intensify the deep color. The mixture is then placed in a large jar filled with water, where it ferments for up to one year.

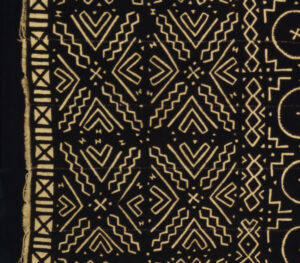

Guancho Diarra, woman’s wrapper (detail), 1985, cotton, vegetal dye, Mali, 61 5/8 x 35 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art)

Once the cloth has been prepared and the dye ready, the painting begins. The distribution of designs on the cloth is carefully considered beforehand, and the spacing measured by hand. The mud dye is applied freehand, beginning with the designs on the borders and working inward. A distinguishing feature of bògòlanfini is that the mud dye is applied to the background, with patterns emerging in white from the painted negative space.

Typically, an artist applies several layers of mud dye to ensure a deeply saturated color. Between applications, the cloth is fully dried and then washed. The cloth then has a final soak in another solution of water and leaves to enhance the darkness of the mud and dried once more. In the last step of the process, a caustic soda, called sodani, is applied to the yellowish areas not painted. The sodani bleaches the patterns, approximating the original white color of the cotton cloth. Diarra’s bògòlanfini is noteworthy for the high contrast she achieves between the light-colored motifs and the dark, mud-dyed areas.

Designs and their meaning

Many bògòlanfini patterns are named and have meanings associated with them. They may refer to objects, animals, people, places, or historical events. Names and meanings of the patterns can vary from one region and from one artist to another. Deeper knowledge of the meanings of the symbols is generally reserved for experienced, expert women.

Small dots run along the top border. Guancho Diarra, woman’s wrapper (detail), 1985, cotton, vegetal dye, Mali, 61 5/8 x 35 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art)

Diarra’s bògòlanfini is designed as a woman’s wrapper, which typically features five fields of design each highlighting a specific pattern. For example, here the small dots that run in multiple rows along the top border are a pattern known as tiga or “peanuts.” In the Beledougou region of Mali, women frequently work in the family’s peanut fields. The symbol is thus associated with the female domain and stresses the responsibilities and power of women.

The repeating pattern on the left side. Guancho Diarra (detail), woman’s wrapper, 1985, cotton, vegetal dye, Mali, 61 5/8 x 35 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art)

On the left, the pattern that is repeated along the left border in two rows is a version of celè ju, or “bottom of the net.” It refers to the net bag a woman uses to carry her belongings or that is used in fishing.

The long line at the bottom. Guancho Diarra (detail), woman’s wrapper, 1985, cotton, vegetal dye, Mali, 61 5/8 x 35 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art)

Pattern on the right side borders. Guancho Diarra (detail), woman’s wrapper, 1985, cotton, vegetal dye, Mali, 61 5/8 x 35 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art)

Other patterns are used to define the five main areas of design. The long straight line running horizontally at the bottom is sa-jè-ni or “little white snake.” The patterned area on the right border is bracketed on either side by zig-zags that run vertically known as cè farin jala or “the brave man’s belt.” The reference is to the belt a warrior or soldier would wear when going off to fight. In wearing a cloth with this pattern, an individual suggests that he or she possesses qualities of bravery.

Bògòlanfini, past and present

Bògòlanfini has traditionally been regarded as inherently powerful, offering a kind of “spiritual armor.” The transformative nature of the artistic process, which requires harnessing the knowledge and materials of the natural world, imbues the cloth with a force the Bamana refer to as nyama or “energy that animates the universe.” Historically, in certain contexts, bògòlanfini was believed to provide protection to the wearer. Young Bamana women would wear a wrapper during ceremonies marking their initiation into adulthood, a major life transition during which they are seen as spiritually vulnerable. Hunters, whose profession often placed them in danger, also wore tunics made of bògòlanfini for their protective function.

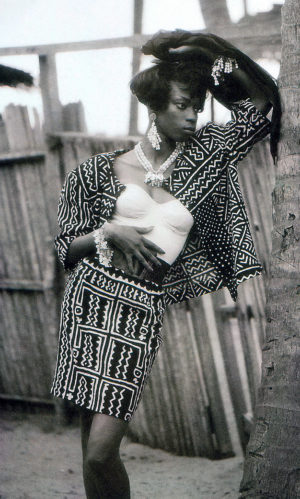

Yet tradition is always dynamic. Today, bògòlanfini is made by both men and women in Mali, often using new, less time-consuming techniques such as stencils and stamps. It has come to be a symbol of national identity, ubiquitous in tourist markets and adopted by fashion designers and studio artists alike in Mali. Abroad, its striking geometric designs have inspired a wide range of items from home furnishings to high fashion.

This wrapper by Guancho Diarra, while no doubt incorporating her own late 20th-century innovations, is a classic example of a long-standing Malian textile tradition that today holds worldwide appeal.

Additional resources

Victoria L. Rovine, Bogolan: Shaping Culture through Cloth in Contemporary Mali (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001).

Nakunte Diarra, a bògòlanfini artist also from Kolokani, Mali, demonstrates the art at the Folklife Festival in Washington, D.C. in 2003.