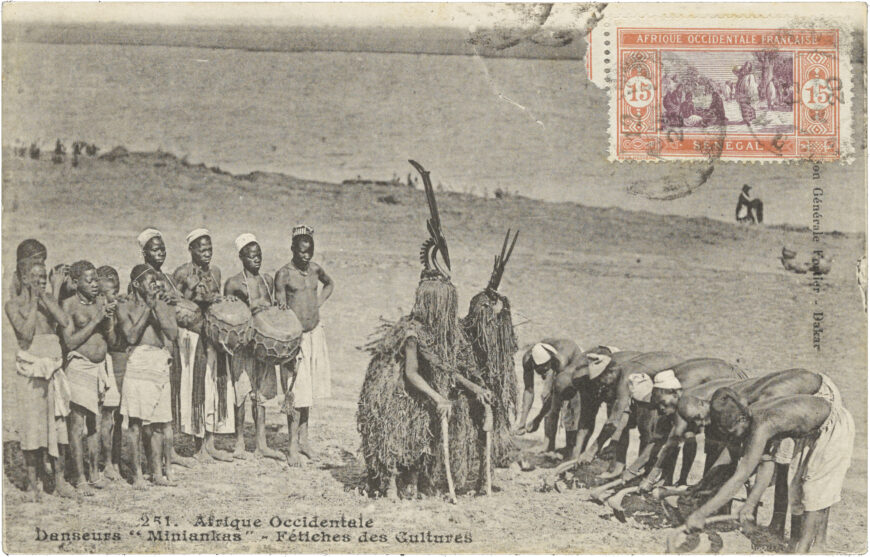

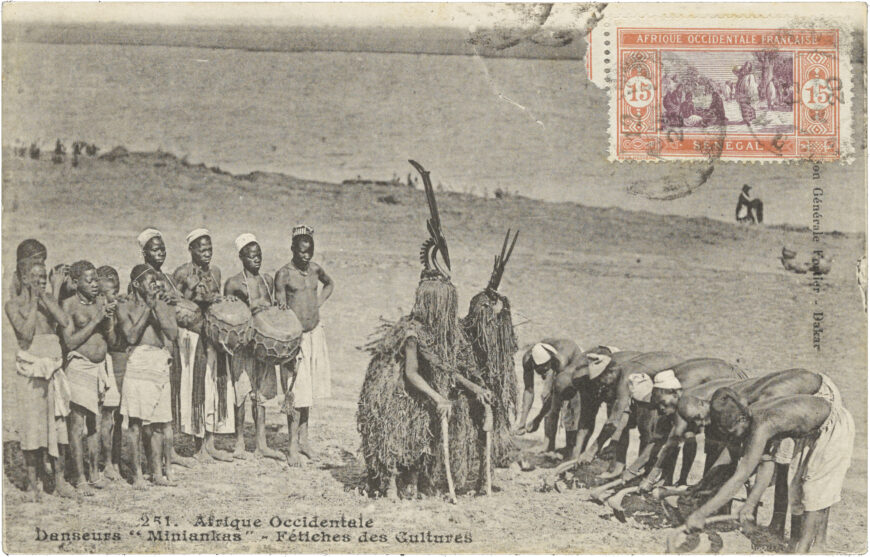

François-Edmond Fortier, Afrique Occidentale – Danseurs “Miniankas” – Fétiches des Cultures, 1905–06 (Senegal), photomechanical print, 13.3 x 8.3 cm, postcard number 251, postmarked 1920 (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

On the back of a postcard from early 20th-century Mali, a pair of performers in the center of the composition are flanked on one side by young men and musicians, and on the other by older men bending down with adzes in their hands. The group stands in an empty, gently sloping field close to the camera, enabling us to examine the scene. The performers wear wooden sculptures on their heads like hats, while their bodies are covered in raffia and cloth. The photograph, known as Danseurs “Miniankas,” depicts a reenactment of a Ci wara masquerade, named for the powerful force identified by communities in southern Mali as the source of all life. The circumstances surrounding the photograph’s creation and its global distribution exemplify how photography was utilized by a variety of people—from colonial ethnographers to Indigenous entrepreneurs—to achieve their different but related aims.

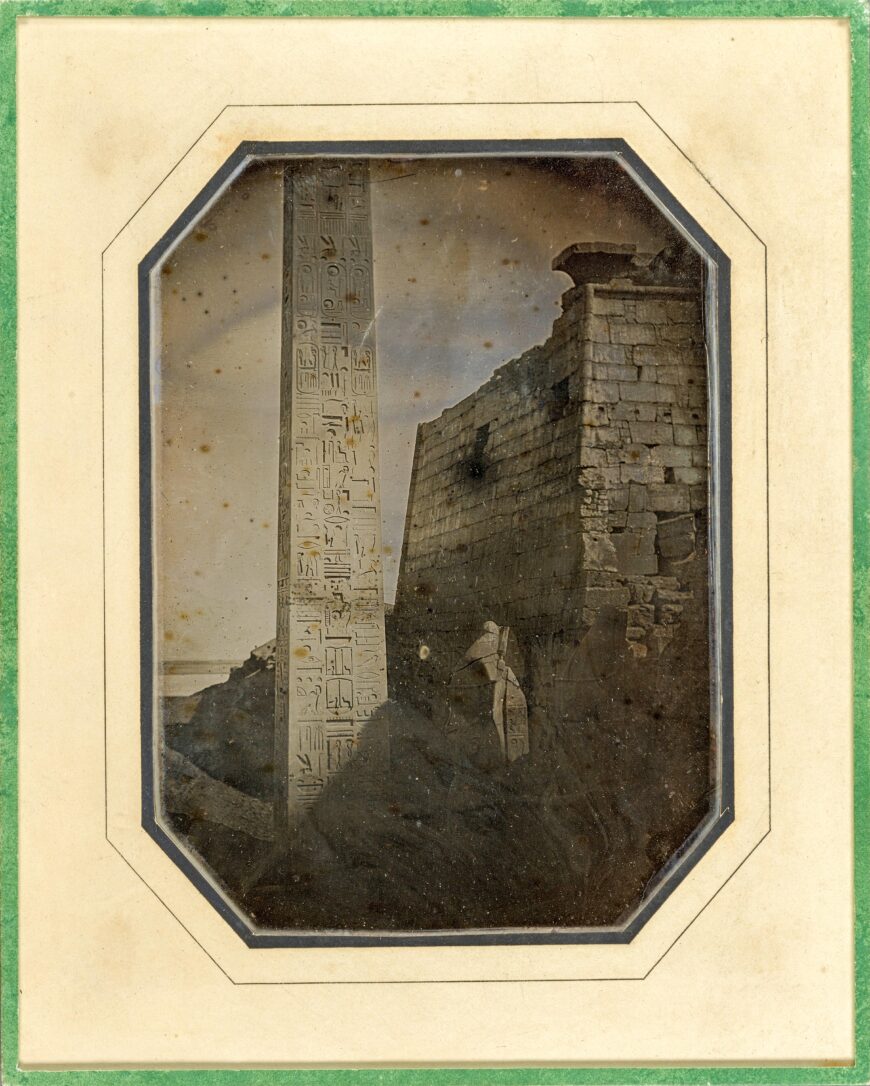

Alphonse-Eugene-Jules Itier, Obelisk and Propylaeum of Luxor, 1845–46, daguerreotype in mount, 21 x 16.8 cm (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Early photography in Africa

Unlike any other artistic medium, photography spread globally almost all at once in the 19th century. Only ten months after the invention was presented in France in 1839, artists began documenting Egypt’s wondrous monuments (like the Great Pyramids) with their cameras. In West Africa, European colonial officials (by this period, France, Portugal, and Spain had colonies in Africa) such as Jules Itier were among the first to employ this technology to record their impressions as they journeyed along the Atlantic coast in the early 1840s. However, the medium was not the monopoly of Europeans.

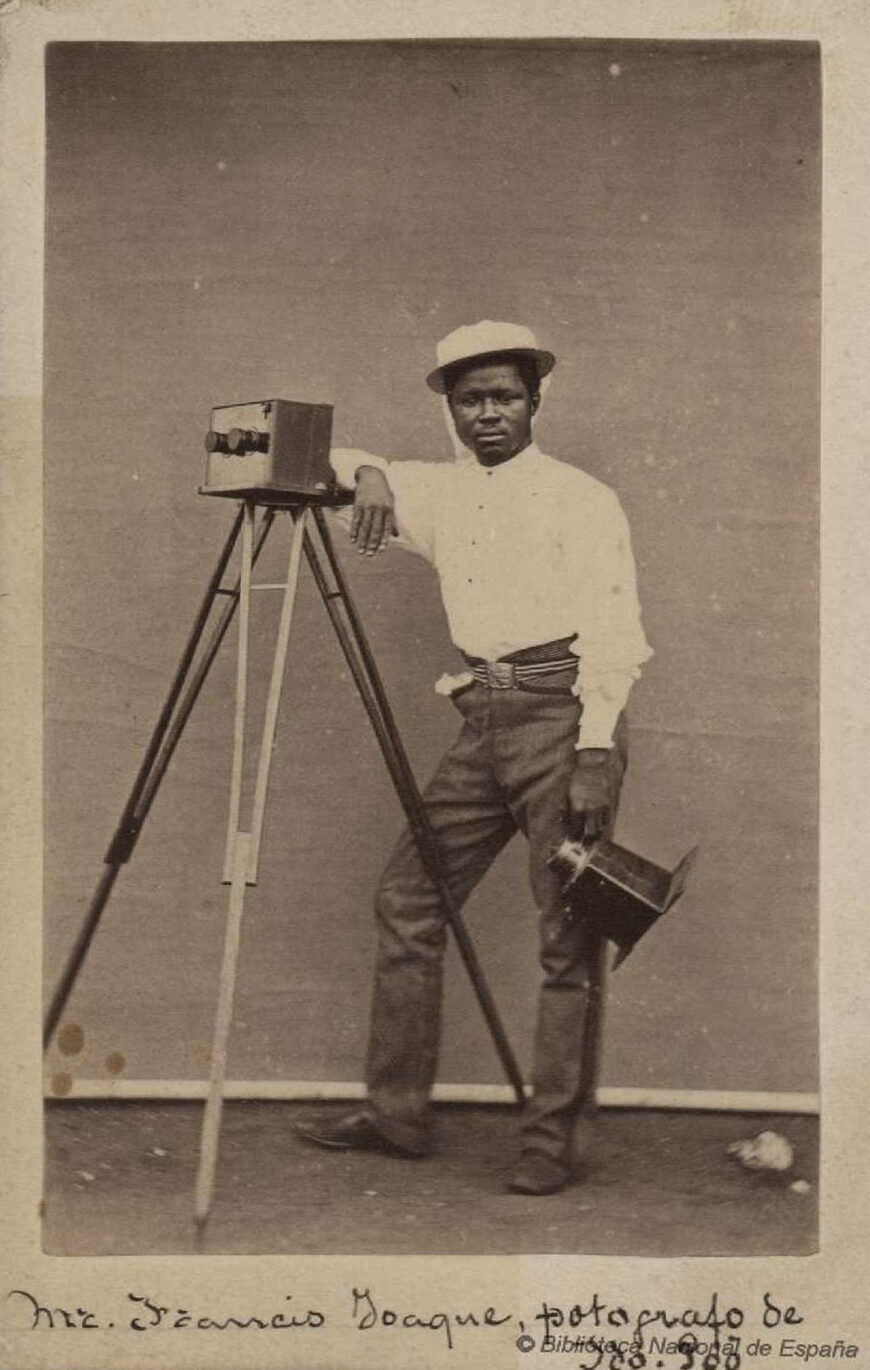

Fernão do Pó, Francis W. Joaque (carte de visite), c. 1875, albumin print, 10 x 6.3 cm (Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid)

African patrons and entrepreneurs quickly picked up the new technology, such as the Sierra Leonean Francis W. Joaque, who was active in the 1870s. Photographers, clients, and images spread across the region rapidly, and by the early 1900s, most West African capitals had established photographic studios. While artists photographed a variety of subjects from the natural landscape to scenes of urban life, portraits have been the most frequently preserved. Postcards featuring photographic images created by both foreign and native photographers became popular commodities during the first two decades of the 20th century. Entrepreneurs maximized their income by selling images not only to the sitter of a portrait, but to a wider audience both locally and internationally. Recent scholarship has demonstrated that studios often reprinted and distributed portraits originally commissioned by private clients in commercial formats such as postcards—with or without the patrons’ consent.

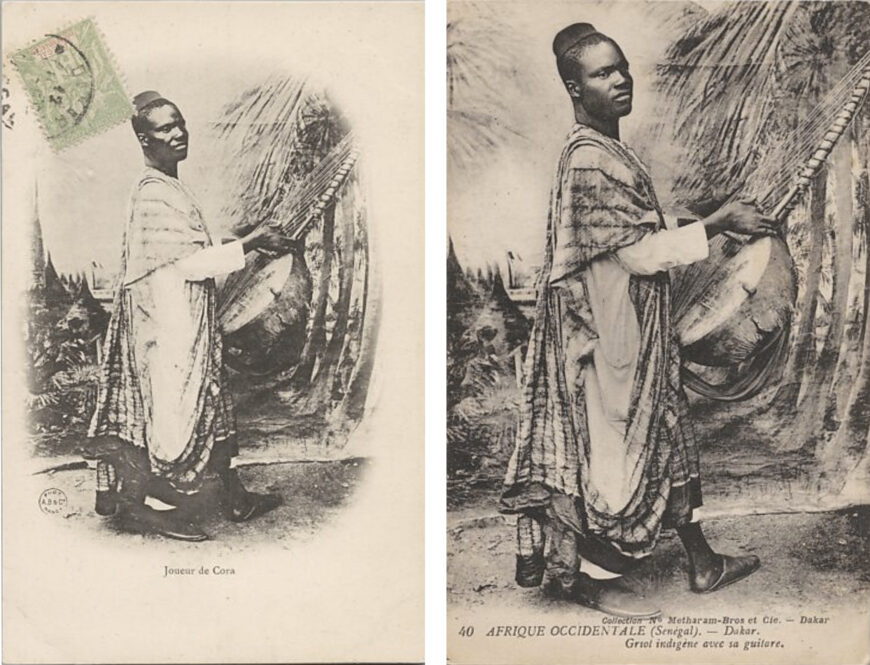

Left: Louis Hostalier, Joueur de Cora, published by A.B. & Co., early 20th century, photomechanical reproduction (postcard), 13.3 x 8.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); right: Louis Hostalier, Afrique Occidentale (Sénégal) Dakar—Griot indigène avec sa guitare, published by Metharam Brothers et Cie, c. 1900, photomechanical reproduction (postcard), 14 x 8.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

For example, Louis Hostalier’s image of a Senegalese griot (historian) was printed on postcards by two different publishers (A.B. & Co. and Metharam Brothers & Cie). While A.B. & Co. cropped Hostalier’s photograph into an ovular format and gave it the simplified title of Kora Player (Joueur de Cora), the Dakar-based Metharam Brothers firm reproduced Hostelier’s photograph at full bleed and gave it a longer and more descriptive title of West Africa (Senegal) Dakar—Native griot with his Guitar. Despite these formal differences, both publishers transform what may have been a portrait to share with friends and family into a generalized type of person. Commonly referred to as “ethnographic types” or “ethnographic scenes,” this genre of images was widely disseminated and preserved through both private postcard sales and the utilization of these images in the burgeoning academic field of ethnography.

Left: dancers (detail), François-Edmond Fortier, Afrique Occidentale – Danseurs “Miniankas” – Fétiches des Cultures, 1905–06 (Senegal), photomechanical print, 13.3 x 8.3 cm, postcard number 251, postmarked 1920 (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.); inset right: Dance Headdress/Ci-wara Kun, late 19th–early 20th century (Bamana), wood, metal, 92.4 x 36.2 x 7.3 cm (Brooklyn Museum, New York)

Ethnographic photography and Ci wara masquerade

In addition to the appropriation of portraits, photographers would stage scenes specifically for these same circuits of commerce as well as for the new field of scientific study termed ethnography. Ethnography as an academic discipline developed alongside European imperial projects: colonial officers studied African cultures in order to facilitate the exploitation of human and natural resources with greater ease and efficiency. Photography was understood to be an objective tool that could be used to record information about so-called “primitive peoples.” Fortier sold this image to several publishers for reproduction in several early 20th-century French anthropological publications. But is this image an accurate portrayal of Ci wara?

Malian religious practices—including a genre of masquerade similar to Ci wara—were first documented in the 1300s by the Moroccan cartographer and cultural historian Ibn-Battuta. His observations, published in Arabic in 1355 and translated into French five hundred years later, continue to provide historians with valuable information about the longevity of cultural forms in Bamana-speaking communities.

François-Edmond Fortier, Afrique Occidentale – Danseurs “Miniankas” – Fétiches des Cultures, 1905–06 (Senegal), photomechanical print, 13.3 x 8.3 cm, postcard number 251, postmarked 1920 (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Closer examination of Fortier’s photograph demonstrates that this scene in fact depicts a re-enactment or staging of Ci wara performance. All the people in the photograph are nearly motionless, evidenced in the fact that you can see their outlines clearly. While Ci wara were typically performed for the entire community in the central square, this group is gathered in an empty field outside the town that can be seen in the upper left corner of the image, further underscoring the staged nature of the photograph.

Fortier and the publishers utilize the term “fètiche” or “fetish” in the caption for this photograph. European merchants in the 16th century created this word to refer to technologies—like Ci wara—deployed by West Africans to maintain their effectiveness as conduits of both spiritual and material resources for their communities. The term gradually took on a derogatory connotation associated with irrationality, and by the early 20th century had become associated exclusively with Afro-Atlantic and Pacific peoples subject to European imperialism.

While we have no records of whether Fortier paid these Ci wara practicioners for their time and expertise, the image demonstrates that Africans actively participated in creating images of their culture for non-local audiences, even as those images were operationalized for colonial ends. François-Edmond Fortier’s image of Ci wara masquerade underscores the complexity of this global process of image production, circulation, and consumption. Through the itinerancy of these entrepreneurs, clients, and images, photography inserted Africans into a global visual economy, as consumers, producers, and patrons.