Beaded collar (ingqosha), early to mid-20th century, unidentified Xhosa artist, South Africa, glass beads, buttons, string; 3 ½ x 12 ¼ inches (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

This broad beadwork collar, or ingqosha, was made by Xhosa-speaking women in South Africa sometime in the early to mid-twentieth century. Thousands of small colored glass beads, sometimes referred to as seed beads, have been painstakingly threaded and woven together to form a flat, semi-circular necklace. Alternating solid bands of pink and turquoise beads are defined by a single line of black beads. A small mother-of-pearl button serves as a clasp at back. From the nineteenth century on, such necklaces were worn by both men and women, sometimes in multiples layered around the neck, on special or ceremonial occasions.

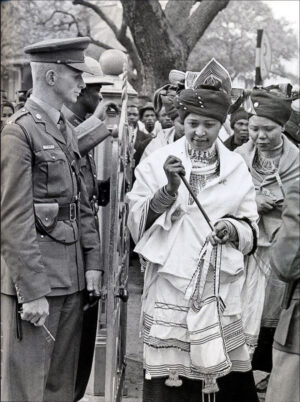

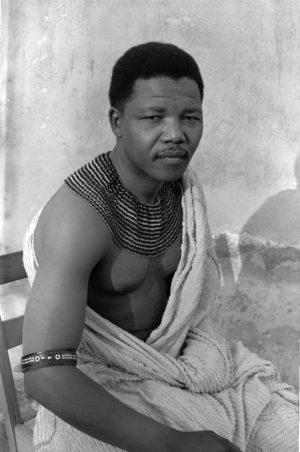

Nelson Mandela wearing a Xhosa beaded collar, 1962, when he arrived at South Africa’s Supreme Court (photo by Eli Weinberg)

The ingqosha was already an iconic form of Xhosa beadwork when it was famously worn in the 1960s by Nelson Mandela, the anti-apartheid political activist who became South Africa’s first president from 1994 to 1999. In October 1962, Mandela arrived at South Africa’s Supreme Court to be sentenced on charges of treason against the apartheid government. Instead of the suit and tie that a lawyer or defendant might typically dress in, Mandela appeared in traditional Xhosa attire wearing a kaross, or cloak, draped over one shoulder, leaving the other bare. Prominent around his neck was a broad beadwork collar. The noisy court was stunned into silence when he entered.

Mandela’s decision to wear traditional dress was a powerful statement. He was expressing his identity as an Indigenous South African by wearing attire associated with its proud and pre-colonial past. In doing so, he was questioning the legitimacy of the trial by making the point that he was a Black African being judged in a white court. It was a statement of defiance. It was so powerful that a photograph of Mandela wearing an ingqosha, released by the African National Congress in the 1960s, was banned from publication in South Africa for nearly three decades under the country’s apartheid government.

How did a relatively humble example of Xhosa beadwork become such a potent symbol of tradition as well as a statement of defiance?

Beadwork

For centuries, beadwork has been a major form of creative expression throughout much of South Africa. It is a women’s art, practiced not only by those in various Xhosa-speaking communities in the Eastern Cape but among Zulu, Ndebele, Sotho and other linguistic groups as well. Historically, Xhosa beadwork was worn by men and women as markers of social roles and status and sometimes, profession. Wearing beadwork also facilitated connections to the ancestral realm. The exchange of beadwork as gifts also expressed and cemented social bonds, typically between women makers and their husbands or boyfriends, as well as between mothers and daughters.

Beaded collar (ingqosha), early to mid-20th century, unidentified Xhosa artist, South Africa, glass beads, buttons, string; 3 ½ x 12 ¼ inches (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Wedding Ensemble for a Bride (Umtshakazi), Thembu, 1950s, cotton cloth, glass beads, mother of pearl beads, thread, and leather, 114 cm high, Eastern Cape, South Africa (Art Institute of Chicago)

South African beadwork in general is widely understood—by cultural insiders and outsiders alike—as traditional attire, associated with the pre-colonial past. However, a closer look gives us a more nuanced understanding of “tradition.” As an artistic practice, beadwork was in fact established in and enabled during the colonial era. The small glass seed beads were imported from Europe, along with metal needles and cotton thread. Glass beads were relatively rare in South Africa until the nineteenth century, when they became more plentiful through expanded trade networks. This led to the growth and development of various forms of beadwork and bead-working techniques. Women, many of whom were taught to sew by white missionaries in the nineteenth century, adapted the needle arts to create increasingly complex and innovative beadwork.

The production of beadwork increased significantly beginning in the late nineteenth century, a period when restrictive laws forced Black South African men into migrant labor in urban areas. On a practical level, the cash that men earned by working in cities paid for raw materials—beads, needles, and thread—that enabled increased production. And as men left their homes to work in mines and other urban industries, women were expected not only to tend rural homesteads but also uphold cultural practices and maintain ancestral links. By the early twentieth century, beadwork became an increasingly important symbol of Indigenous values and beliefs in the face of social change.

Because of its traditional significance, beadwork directly conflicted with the “civilizing” aims of white Christian missionaries. They condemned beadwork, associated with spirituality and used to communicate with ancestors in Xhosa-speaking communities, as a “heathen” practice. Traditionalists, especially those in more rural communities, continued to wear beadwork as a symbol of resistance to attempts to redefine African identity and culture in the colonial era.

Beaded collar (ingqosha), early to mid-20th century, unidentified Xhosa artist, South Africa, glass beads, buttons, string; 3 ½ x 12 ¼ inches (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Over the course of the twentieth century, South African beadwork was increasingly seen as traditional and associated with specific ethnic identities. Collections of beadwork in museums are often labeled as Xhosa or Zulu, though, in the nineteenth century at least, these ethnic classifications were not rigidly defined. Beginning in the early twentieth century, certain styles and colors of beadwork came to signify belonging to a particular people or a place. Wide collar necklaces, such as this one, were generally made and worn among Xhosa-speaking communities. Color combinations sometimes reflect regional or ethnic preferences within the broader Xhosa linguistic group. For example, the combination of colors seen on this collar—turquoise, pink and white—is usually associated with Mfengu artistic practices while the collar that Mandela wore is usually described as Thembu.

Beadwork became a visual marker of cultural identity in an era in which formerly fluid ethnic and regional identities were becoming increasingly fixed through government policies. Following the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910, Black people were increasingly disenfranchised, segregated, and ultimately “retribalized” by the government, which sought to highlight ethnic difference. The institutionalization of ethnic consciousness was part of a divide-and-conquer strategy that exploited existing tensions in order to support white minority rule. The apartheid government, which came to power in 1948, eventually established “homelands,” an insidious system of ten separate nation-states for different Black cultural groups.

In the 1960s, when Mandela chose to don a Xhosa ingqosha, there was intense public debate about whether Black political leaders should wear “tribal” dress. Some feared that beadwork and other forms of traditional dress would reinforce ethnic divisions exploited by the apartheid government. Yet others saw the value of beadwork as an instrument of political mobilization. Among them was Mandela’s wife at that time, Winnie, who similarly donned an ingqosha for a public appearance during her husband’s trial.

We are not going to rub off our culture and traditions because of the fear that the Nationalists will make propaganda of them. We are Africans and need not regret we were born Africans.Winnie Mandela [1]

Notes:

[1] Winnie Mandela, quoted in Sandra Klopper and André Proctor, “Through the Barrel of a Bead: The Personal and the Political in the Beadwork of the Eastern Cape,” in Ezakwantu: Beadwork from the Eastern Cape (Cape Town: South African National Gallery, 1994), p. 62.

Additional resources

Sandra Klopper and André Proctor, “Through the Barrel of a Bead: The Personal and the Political in the Beadwork of the Eastern Cape,” in Ezakwantu: Beadwork from the Eastern Cape (Cape Town: South African National Gallery, 1994), pp. 57-65.

Sandra Klopper, “From adornment to artefact to art: historical perspectives on south-east African beadwork,” in South East African Beadwork 1850–1910: From Adornment to Artefact to Art, ed. Michael Graham-Stewart, pp. 9–43 (Fernwood Press, 2000).

Anitra Nettleton, “Inventing ‘African Traditions’ in South Africa.” Art Africa, 2018.

Gary Van Wyk, “Illuminated Signs: Style and Meaning in the Beadwork of Xhosa- and Zulu-speaking Peoples,” African Arts, vol. 36, no. 3 (2003).

Read more about the Union of South Africa on South African History Online.