![Seydou Keïta, Untitled [Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress], 1956, printed 1997, Mali, Bamako, gelatin silver print, 60.96 x 50.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) © Seydou Keïta](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Screen-Shot-2022-08-10-at-9.28.40-AM.png)

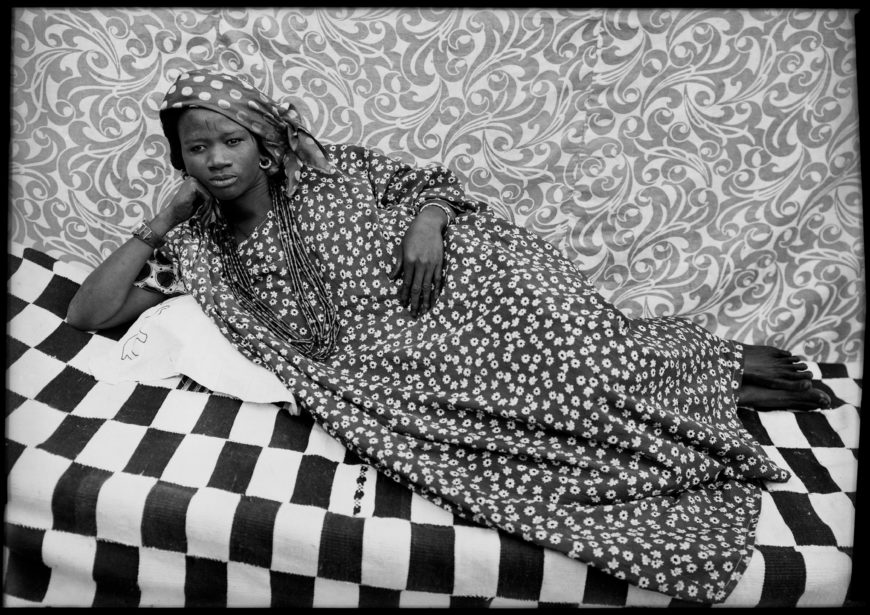

Seydou Keïta, Untitled [Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress], 1956, printed 1997, Mali, Bamako, gelatin silver print, 60.96 x 50.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) © Seydou Keïta

Among the busiest portrait studios in Bamako was that of photographer Seydou Keïta. Born in 1923, Keïta originally apprenticed as a carpenter but found his vocational calling when he was given a 6 x 9 Kodak Brownie camera by his uncle. After experimenting on his own, Keïta learned darkroom techniques from two established commercial photographers. He opened his own studio in 1948 in Bamako-Koura, an area of the city whose proximity to a train station and popular marketplace ensured a steady stream of potential clients.

Keïta soon became highly successful as a commercial photographer, producing tens of thousands of portraits over the course of his career. He developed a consistent and recognizable signature style that proved popular with local clients, who requested that their prints include a stamp with Keïta’s name. A typical sitting took place during the day in his outside courtyard and could last up to an hour. Keïta gave his sitters the opportunity to individualize their portraits, helping them select a flattering pose and offering a variety of accessories as props. He posed his clients against a printed cloth, which often resulted in vibrant juxtapositions between the patterns of the sitter’s clothes and that of the backdrop. Other compositional strategies included the use of a shallow depth of field and an emphasis on repetition and symmetry in framing his subject.

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1956–57, gelatin silver print, 39.1 x 55.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) © Seydou Keïta

In this portrait, a woman reclines on her side with a relaxed and self-possessed dignity. The tight cropping places the focus entirely on the sitter, while the camera angle makes her appear on a slightly tilted slope, creating a symmetrical composition. The floral print of the woman’s boubou (a traditional form of dress) contrasts with the bold black and white checkered blanket in the foreground and the swirling arabesques of the cloth backdrop, creating a syncopated clash of patterns and rhythms. Her dress and pose communicate significant aspects of her identity, revealing how traditional concepts of portraiture are maintained and modified through the medium of photography. Her head wrap is worn in a trendy style called à la Gaulle, its jaunty angle framing the scarification marks of ethnic affiliation that she bears on her forehead. She rests her left arm casually at her waist, dangling her long slender fingers, which are considered a sign of high social standing.

When Mali won independence from France in 1962, Keïta was offered a position as official government photographer, where he remained until 1977. His governmental responsibilities required him to close his studio in 1964 and he never reopened his portrait practice, although he did continue his photography. Beginning in the 1990s, Keïta’s work was included in several exhibitions in the United States and Europe, bringing him considerable fame in the international art world.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)