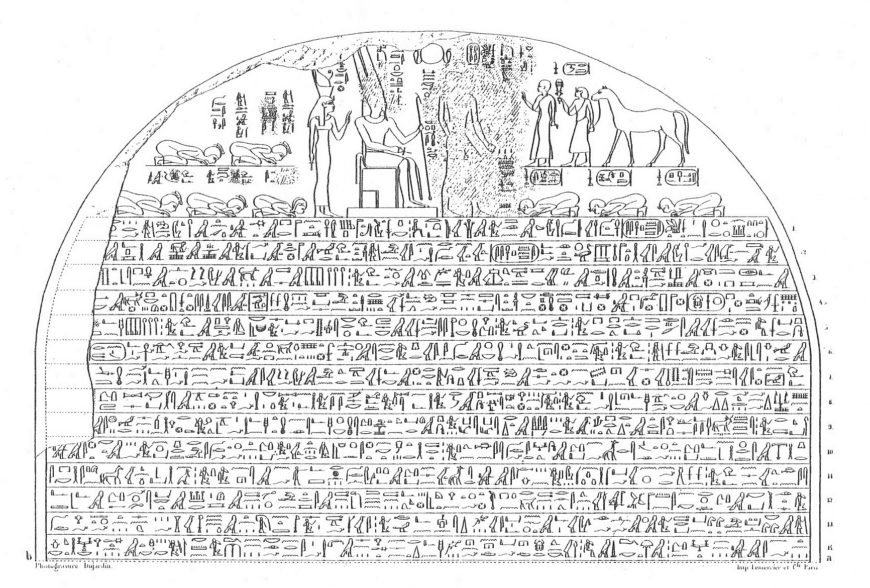

Drawing of the upper part of the victory stele of pharaoh Piye. The lunette on the top depicts Piye being tributed by various Lower Egypt rulers, and the text describes his successful invasion of Egypt. Original stele in granite, found at Jebel Barkal and datable to the reign of Piye, 25th dynasty, now in the Cairo Museum.

Who was king Piye?

Piye, also called Piankhy (747–716 B.C.E.) and Kushite ruler of the Napatan period, laid the foundations for the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt (747–656 B.C.E.). He seized control of Upper Egypt within the first decade of his reign, and his sister Amenirdis I was adopted by Shepenwepet I as the next God’s Wife of Amun, thus acquiring Theban territories previously controlled by Osorkon III. In 728 B.C.E., when Tefnakht, the prince of Sais, created an alliance of Delta rulers to counter the growing Nubian threat, Piye swept northwards and defeated the northern coalition. His successful campaign is described on his Victory stela.

Pyramid K.1, 4th century B.C.E., at El-Kurru, south of Jebel Barkal, North Sudan (photo: Betramz, CC BY 3.0)

In 716 B.C.E. Piye died after a reign of over thirty years. He was buried in an Egyptian style pyramid tomb at El-Kurru, accompanied by a number of horses, which were greatly prized by the Nubians of the Napatan period. Piye was succeeded by his brother Shabako (716–702 B.C.E.) who re-conquered Egypt and took full pharaonic titles, establishing himself as the ruler of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of all Egypt.

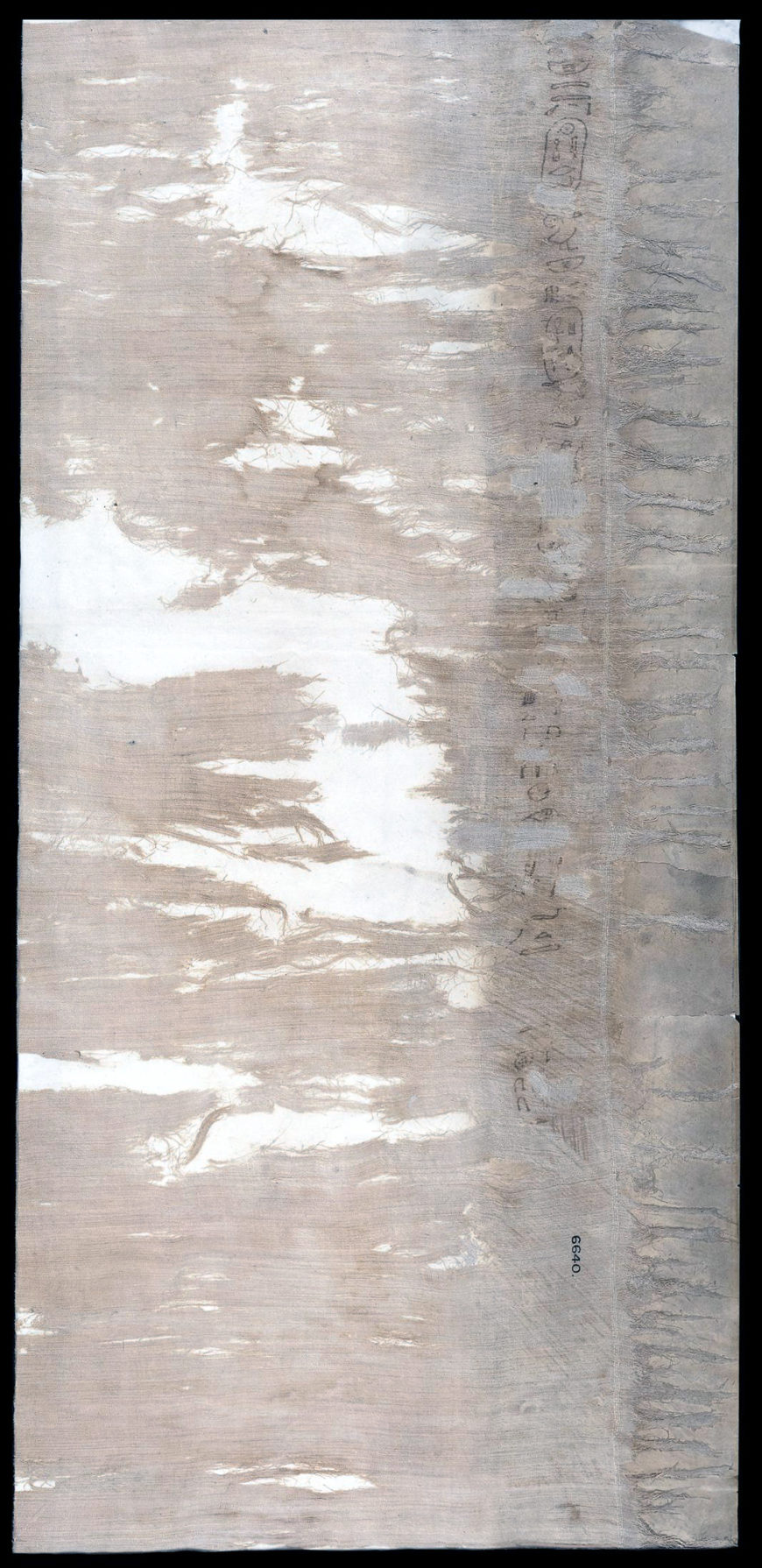

An Egyptian textile that tells of a Kushite king

Textile with names of King Piye (detail), 25th Dynasty, around 712 B.C.E., from Thebes, Egypt (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Textile with names of King Piye near the fringed edge, 25th Dynasty, around 712 B.C.E., from Thebes, Egypt (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Vast quantities of linen were used in the daily rituals of Egyptian temples. Some of this linen was donated, often inscribed with the name of the donor. This piece of high quality linen was donated by the Kushite king Piye to a temple of Amun-Re, possibly at Karnak. A column of inscription, close to the fringed edge of the cloth, gives the king’s titles and a year date, presumably the year of king Piye’s reign.

The year date is fragmentary. Two symbols for the number ’10’ survive, indicating that the date must be higher than Year 20. The most likely reading of the group is ‘Year 30’, but ‘Year 40’ has also been proposed. In either case, this is the highest known year of reign for this king.

The relatively good condition of the cloth suggests that it found its way into a tomb. Food offerings in temples were returned to the priests once the gods had magically taken what they wanted. The same was the case for other items used in everyday cult activities. When linen cloths became too old to use, they could be given to priests for their burials, although some might have been given directly to favored officials by the king.

Bronze door hinge bearing names of God’s wives of Amun, inscribed with the names of Amenirdis I and Shepenwepet II, 25th–26th Dynasty, 760–650 B.C.E., from Egypt (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Objects that speak to the Kushite royal family

This hinge is of massive proportions, and probably belonged to one of the many monumental doorways of a Theban temple. Although there are extensive remains of the stone parts of these structures, little remains of the door and doorway furniture and fittings, which were often taken down and reused.

The hinge is inscribed with the names of Amenirdis I and Shepenwepet II, both of whom successively held the office of God’s Wife of Amun. Amenirdis was the sister of King Piye, who was the first major ruler in Egypt of the Kushite Dynasty (referred to as the Twenty-fifth Dynasty). He installed his sister in this important religious office in order to maintain control of the southern region of Egypt, administered from Thebes. The holder of the office was celibate, and the successor was adopted by the current holder. Amenirdis adopted Piye’s daughter, her own niece, Shepenwepet II.

The names of the women appear in cartouches because they were considered to be the spouses of the god, and also because they were members of the Kushite royal family. The name of Piye, in the central cartouche, has been deliberately erased. This was probably done during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty when native Egyptian rule was restored.

King Taharqa introduced more Egyptian elements to burial

Granite shabti of King Taharqa, 25th Dynasty, 664 B.C.E., from the pyramid of Taharqa at Nuri, Nubia, 40.6 cm high (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Egypt was brought partially under Kushite domination by Piye (reigned about 747–716 B.C.E.). On his commemorative stela he claims that he was acting with the blessing of the god Amun to restore order to the country. At the time, Egypt was politically divided into small areas, governed by local dynasts who often styled themselves as kings.

It was the ambition of Piye and his successors to restore Egypt to greatness. Unfortunately, their intervention in political affairs in Palestine brought Egypt to the attention of the Assyrian empire. King Taharqa (690-664 BC) eventually lost Egypt to the Assyrians. The country was regained only briefly by his successor Tanutamun (664–656 B.C.E.).

The early Kushite kings were buried on beds placed on stone platforms within their pyramids. These structures were based on the pyramidia of Egyptian private tombs of the New Kingdom (about 1550–1070 B.C.E.), but the burials were entirely Kushite. Taharqa introduced more Egyptian elements to the burial, such as mummification, coffins and sarcophagi of Egyptian origin, as well as the provision of shabti figures. These figures were in the style of the Middle and New Kingdoms, the era that the Kushites considered as the height of Egyptian culture. The use of stone, an obsolete early shabti-formula and the rugged features of these large shabti are characteristic of early examples.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Additional resources:

J.H. Taylor, Egypt and Nubia (London, The British Museum Press, 1991)

R. Parkinson, Cracking codes: the Rosetta St (London, The British Museum Press, 1999)

J. B. Greene, Fouilles exécutées à Thèbes da (Paris, Firmin Didot frères, 1855)