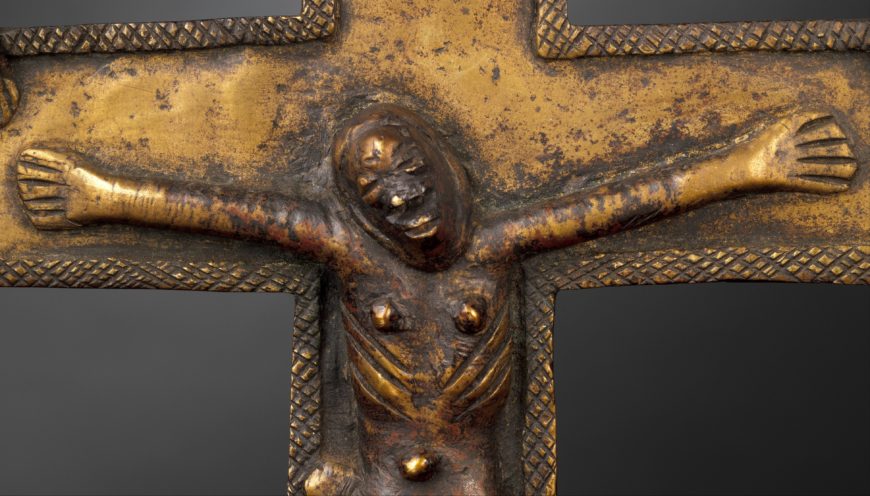

Crucifix, 16th–17th century, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kongo peoples, solid cast brass, 27.3 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

When Portuguese explorers first arrived at the mouth of the Zaire River in 1483, the Kongo kingdom was thriving and prosperous, with extensive commercial networks between the coast, interior, and equatorial forests to the north. Portugal and Kongo soon established a strong trading partnership. In addition to material goods, the Portuguese also brought Christianity, which was rapidly adopted by Kongo rulers and established as the state religion in the early sixteenth century by King Afonso Mvemba a Nzinga. The adoption of Christianity allowed Kongo kings to foster international alliances not only with Portuguese leaders but also with the Vatican. In response to their new faith, Kongo craftsmen began to introduce Christian iconography into their artistic repertoire.

Detail, Crucifix, 16th–17th century, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kongo peoples, solid cast brass, 27.3 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Detail, Crucifix, 16th–17th century, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kongo peoples, solid cast brass, 27.3 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This crucifix demonstrates how Kongo artists adapted and transformed Western Christian prototypes.

Although the general depiction of the central Christ figure with arms extended follows Western conventions, the features of the face are African. The presence of four smaller figures with clasped hands—two seated on the top edges of the cross, one at the apex, and one at the base—is a departure from standard iconography. These figures are more abstract and remote, in contrast to the expressionistic treatment of Christ.

Western forms like the crucifix resonated profoundly with preexisting Kongo religious practices. In Kongo belief, the cross was already regarded as a powerful emblem of spirituality and a metaphor for the cosmos. An icon of a cross within a circle, referred to as the Four Moments of the Sun, represents the four parts of the day (dawn, noon, dusk, and night) that symbolize more broadly the cyclical journey of life.

Kongo kings, having adopted Christianity as the state religion, commissioned locally made crucifixes for use as emblems of leadership and power. These crucifixes were cast with copper alloys. The use of copper, a valued import from Europe, reinforced the association with wealth and power. Although Christianity was eventually rejected by the Kongo in the seventeenth century, such works continued to be made as symbols of indigenous cosmological concepts.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)