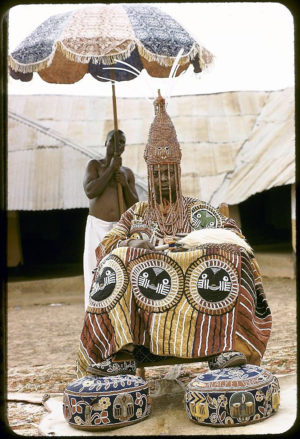

Oba Adémúwàgún Adésidà II, the forty-second Dejì, in the courtyard of his palace at Akúré, 1959 (photograph by Eliot Elisofon, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

On November 19, 1959, Oba Adémúwàgún Adésidà II posed in the courtyard of his palace in Akúré, Nigeria for Life magazine photographer Eliot Elisofon. He had recently assumed the throne as the forty-second Dejì, or traditional ruler, of Akúré, a centuries-old Yorùbá kingdom in the south-west part of the country. The thirty-four-year-old Dejì was an attorney who had studied law in Dublin and passed the bar examination in London. Now in Akúré, where his authority extended over more than 100,000 people, he was focused on introducing electricity and piped water into the city.

Elisonfon was on assignment for a Life magazine feature on the “new” Nigeria; with its first federal election a month away, the country was poised for independence after almost seven decades of British colonial rule. The position of traditional rulers, like the Déjì, was uncertain within this changing political and social landscape. And so, it is significant that the cosmopolitan ruler presented himself in a ceremonial gown with regalia, rather than a suit and tie, for this formal portrait.

In Elisofon’s photograph, he sits on a throne flanked by two young court attendants bearing ceremonial swords (not visible in the photograph above). On his head, the Déjì wears a tall, beaded crown with a veil that obscures his face, underscoring his sacred nature. His feet, in elaborately beaded slippers, are supported by beaded foot cushions placed on a lion skin rug. In his hands, he holds a beaded whisk. But it is the Deji’s magnificent robe that dazzles above all in his public presentation. A close reading of the robe and its many layers of meaning reveals much about how dress serves as a marker of power and status. It also tells a story about regional politics, cultural interaction, and artistic innovation.

Ceremonial robe (agbádá ìlèkè), late 19th–early 20th centuries, unrecorded Yorùbá artists; Akúré, Ondo region, Nigeria, velvet, cotton, glass beads, 50 x 104 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC 2.0)

A magnificent robe

Cloth (aso oke), Yorùbá, c. 1900–20, cotton and silk, 186 x 139 cm, Nigeria (© Trustees of the British Museum)

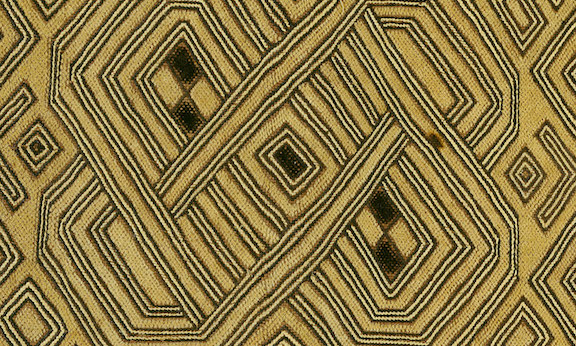

The Deji’s robe is made of velvet, a luxury import that emphasizes the ruler’s privileged access to foreign goods. The tailor who made the garment used variously colored velvets—primarily in shades of deep red and gold—that were then cut into long strips and sewn together. The pieced-together technique is meant to emulate a type of Yorùbá prestige cloth known as aso oke, which is made from narrow strips of hand-woven cloth. This additional and unnecessary step in the fabrication process is solely for impact: using one high-status textile to imitate another effectively doubles down on the prestige quotient. Further elevating an already sumptuous garment, the robe is adorned front to back with thousands of tiny glass beads, another expensive imported good. According to Yorùbá beliefs, embellishment with beads, symbolic of royalty, increases the ritual potency of the regalia.

In style, the Dejì’s robe is an example of the type of large, loose-fitting gowns worn by elite men as prestige attire across western Africa. Such gowns typically are fashioned from strip-woven silk or cotton cloth and intricately embroidered. They are made intentionally wide, to be worn with the voluminous sleeves bunched at the shoulders. This “aesthetic of bigness” enhances the physical presence and symbolic importance of the wearer. Although the garments are historically associated with Islamic faith and lifestyle, they are not expressly religious. In fact, they became fashionable in non-Islamic communities, including among Yorùbá kingdoms, as in the example here.

Ceremonial robe (agbádá ìlèkè) (back), late 19th–early 20th centuries, unrecorded Yorùbá artists; Akúré, Ondo region, Nigeria, velvet, cotton, glass beads, 50 x 104 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art)

Islamic designs and Yorùbá knowledge

Robe (riga), 1920s, unrecorded Hausa artists, Zaria, Nigeria, cotton, wool; 57 x 103 inches (Newark Museum of Art)

The Dejì’s robe is a Yorùbá version of the Hausa-Fulani riga, a particularly important and influential dress tradition that developed among Islamic political and religious elite to the north. The riga, or “robe of honor,” was associated with members of the ruling class in the Sokoto Caliphate (c. 1810–1908), a powerful federation of emirates located in what is now northern Nigeria. Worn during investiture ceremonies and distributed as gifts to high-ranking officials, these visually stunning robes played a critical symbolic role in maintaining unity and central authority. The lavishly embroidered designs, drawn from an Islamic visual vocabulary, refer to political leadership and offer protective powers. Popular motifs include tambari, or king’s drum, a spiral on the wearer’s right chest that signifies Hausa chieftaincy and serves a talismanic function. Also commonly seen are a series of elongated triangles in groups of two or eight, referred to as “knives,” that symbolize wealth.

The four faces on the robe are a Yorùbá version of tambari. Ceremonial robe (agbádá ìlèkè), late 19th–early 20th centuries, unrecorded Yorùbá artists; Akúré, Ondo region, Nigeria, velvet, cotton, glass beads, 50 x 104 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art)

The adoption of a Hausa-Fulani dress genre for the Deji’s robe reflects the powerful influence of the Islamic north among Yorùbá kingdoms to the south. The Yorùbá robe, however, is an adaptation that reflects culturally relevant materials and designs. In addition to substituting velvet for the usual strip-woven cloth, replaces embroidery with beadwork. Vertical lines of beadwork run down the long pieces of velvet, accentuating the visual effect of strip woven cloth. Concentric beadwork circles highlight the voluminous sleeves. Hausa-Fulani designs have been adapted or reinterpreted as Yorùbá icons of power. On the wearer’s left, five long arrows of beadwork point downward, evoking the “two knives” or “eight knives” motifs typically seen on a riga.

Ceremonial robe (agbádá ìlèkè) (detail), late 19th–early 20th centuries, unrecorded Yorùbá artists; Akúré, Ondo region, Nigeria, velvet, cotton, glass beads, 50 x 104 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC 2.0)

On the right, a large circle with four faces suggests the circular form of the sculpted wooden tray used in Ifá divination, the source of sacred knowledge among Yorùbá. Its circular design replaces the spiral motif known as tambari, typically found on the wearer’s right chest, while retaining its protective symbolism. A similar design is at the center on the back of the robe, suggesting that its wearer is safeguarded on either side. The smaller beadwork faces reference the original Yorùbá kings, situating the Dejì within the royal lineage as a sacred descendant of its founding deity, Odùduwà.

Ceremonial robe (agbádá ìlèkè) (detail), late 19th–early 20th centuries, unrecorded Yorùbá artists; Akúré, Ondo region, Nigeria, velvet, cotton, glass beads, 50 x 104 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Color symbolism

Scholars have described how the beadwork designs also draw upon Yorùbá color symbolism. The majority of the small faces are beaded in black, a color exalted in the Yorùbá phrase dúdú bí Ifá, or “black like Ifá.” The color’s association with Ifá divination and its sacred knowledge suggests that its symbolic value lies in its ability to mediate between the spiritual and human realms, linking it with the small faces made with green beads at the top on both the front and back of the robe.

Ceremonial robe (agbádá ìlèkè) (detail), late 19th–early 20th centuries, unrecorded Yorùbá artists; Akúré, Ondo region, Nigeria, velvet, cotton, glass beads, 50 x 104 ½ inches (Newark Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Green is considered a dark color and one that is regarded as having the ability to mediate between colors that are hot, like red, and cool, like white. Because of this, green is a color that, along with yellow (seen throughout), is also worn by diviners who are themselves seen as mediators between the earthly realm of human and the spiritual world of the gods. Rulers, like diviners, are also mediators.

The power of a ruler

Certainly, the Dejì of Akúré must have been highly conscious of his position and responsibilities within this “new” Nigeria when he donned the opulent beaded velvet robe to sit for Life magazine. The photographer acknowledged the Dejì’s position, describing him as “a young European-educated leader who holds a tradition-encrusted throne, and is attempting to reconcile the two cross-currents.” [1] The Déjì’s choice of dress was intended to emphasize the power and authority of traditional systems of leadership at a time of rapid change. But it also reflects a longer history of complex cultural interactions between north and south in a country on the verge of self-determination as a free and united Nigeria.